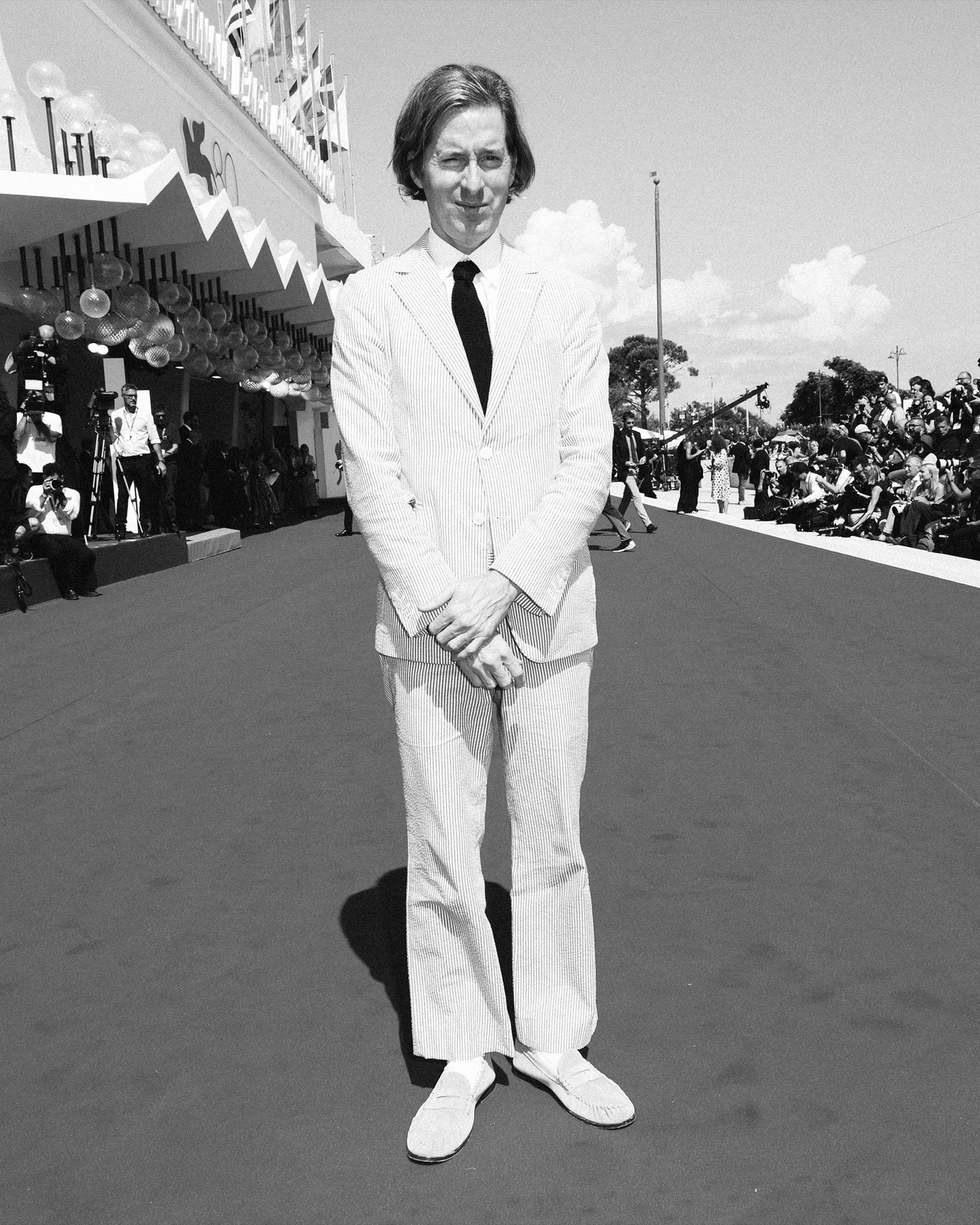

Photo: Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images

Wes Anderson hasn’t premiered a movie at the Venice Film Festival in 16 years, but he spends a lot of time in the Italian city. “I’ve been here much more as a wandering tourist.” he says, sitting under a stone veranda in the garden of an isolated Venetian island villa. This is where he likes to stay every time he visits. It’s stiflingly hot, but he’s in slacks and a long-sleeve shirt, his fair hair brushing his shoulders. It’s a uniform he’s hardly adjusted since he started making his offbeat indie comedies in the 1990s.

The day prior, Anderson had returned to the festival to present The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, a zippy and inventively formed short film for Netflix based on a story by the British children’s author Roald Dahl. Featuring a nesting egg of characters—played interchangeably by what Anderson calls his “company” of actors: Benedict Cumberbatch, Dev Patel, Ralph Fiennes, Richard Ayoade, and Ben Kingsley—it tells the tale of a selfish and wealthy Englishman (Cumberbatch) teaching himself how to see without his eyes. A moral fable of the kind Dahl made a staple, the story’s titular character follows the preternatural advice of a yogi (Kingsley) and uses his newfound knowledge to gamble. (Anderson was also on hand to collect the Cartier Glory to the Filmmaker Award, a festival prize bestowed on the likes of Ridley Scott, Abel Ferrara, Spike Lee, and Agnès Varda in recent years.)

Here, Anderson unpacks how that company came together to make the project, at times eating and living under the same roof; the extent of his ambitions as a theater director; and the Grand Budapest Hotel musical that ever was.

Vogue: For the first time in a long time, you could pretty much fit the cast of your film around a dinner table.

Wes Anderson: It’s true. Most of the actors play at least two people, so that reduces the number of actors we got. Our house was near the film’s set [in Maidstone, England], so Ralph and Benedict and Rupert Friend [who appears in the other shorts] all lived in our house during the shoot. Richard Ayoade was less than an hour’s drive away, so he stayed at home with his family. Ben Kingsley—who we loved—didn’t want to live in my house, which is completely understandable, and Dev usually came to dinner, but he stayed in the same place as Ben.

But yes, we did fit around a dinner table. But we also had the director of photography, the key grips, the script supervisor Jen Furches [Roman Coppola’s wife], and a few others working on it staying with us. Benedict got COVID on the last day, and that meant he stayed in our house for another week. He had a walkie talkie and was totally asymptomatic so he spent much of that time lying in the sun.

I remember reading Dahl’s short story “The Landlady” and realizing that this man who was capable of so much childhood whimsy and inspiration was also capable of something so much…

Darker.

Right. Do you remember when you realized he was capable of doing that too?

I remember thinking some of the children’s ones were pretty dark. He loves a villain who’s not just bad, but is nasty, awful, in every possible way. He loves to invent ways to make someone really deplorable and disgusting. But I think, maybe when I was [in high school], I came across one of his books for adults in a bookstore.

I don’t want to say that; they’re not exactly for adults. They are for anybody, but they’re not limited to adults because they’re stories written with a real twist. He couldn’t resist writing a story that has what most cinema has, and that a lot of literature doesn’t have. You could compare Dahl to Henry James or Marcel Proust.

You’ve now exclusively adapted Roald Dahl for the screen. Is the way you visualize his writing unique, in that sense?

Well, I think it probably just sort of happened. I wanted to do Fantastic Mr Fox because I wanted to do a stop motion animated film, and it’s one I loved as a child and I just kind of mixed those two ideas together. Then I got to know the family. I had some conversations with them and I think Liccy [Felicity Dahl, Roald’s wife] probably said, “Is there another one you like?” So Henry Sugar was set aside for me. It’s not necessarily that I think Dahl is the most adaptable writer, although he might be one of the most adapted writers ever, maybe the most. I genuinely would rather take the inspiration of someone and combine it with something else that might be informed by what I’ve read that I can create my own version from.

Does this company work across all four of these short films?

Yes, but different mixtures. Poison is Benedict, Ben Kingsley, and Dev Patel. The Ratcatcher is Ralph, Rupert, and Richard. But they’re all mixtures of the same group.

Who did you show a film to first after you’ve finished?

My wife and daughter are coming in and out of the cutting room with some regularity. They have their own comments, but it tends not to be the finished thing. Juman, my wife, might say, “Okay tell me when you want me to see the whole thing.” But I have a few friends I rely on. I used to do a thing where I’d try to show a new film to directors I know who can give me [their] take. There was a period of time when I had a whole group. Actually some of them died; when we made Fantastic Mr. Fox we showed it to Mike Nichols and to Jonathan Demme.

Do you have others you rely on now instead?

I have Roman Coppola, my old friend. He’s one person I have to turn to for help. Then I have a little trio of directors: Noah Baumbach, Brian de Palma, and Jake Paltrow. The four of us have a little club that we do in New York. The three of them will watch something [I’ve made], often together, or if one of them is doing something we all see it. It’s a little like knowing someone else who’s a policeman or who’s been in a war zone. You can describe it, but someone who’s been there, you connect with them in a different way.

You have had such a strong influence on other artists, but I’ve noticed that there have been no adaptations of your work for the stage. Have any been presented to you before?

I’ve had a few of them. Somebody had an idea for The Grand Budapest Hotel that had some songs, and they recorded some demoed versions of them. They put it together but I don’t know exactly what happened. I expect they take it to a group of investors and either they invest or they don’t. I think it must have fizzled out. I don’t actually remember.

I don’t think I’ve ever said, “Yes, you can do this,” but I do think I’ve said, “Okay, let me know what happens next and I’ll tell you whether I’m with you or not.” But I think I would like to.

Do you like going to the theater?

I do like going to the theater. If it’s bad, it’s kind of the worst. But if it’s great, it’s kind of the best.

And you’re not opposed to the idea of directing a play yourself?

I’m not opposed to it. The one thing with a movie is that it’s done. With a play, it’s got to be done [repeatedly] and it can go wrong, and you don’t have the opportunity to say, “This part can be better.” The other thing is, when you do a play, you know the opening date before you start rehearsing. With a movie, you have time to keep polishing. With a play, you’ve got to be ready. I find that a bit frightening.

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar will be released in select theaters on September 20, and on Netlix from September 27.

This article was originally published on Vogue.com