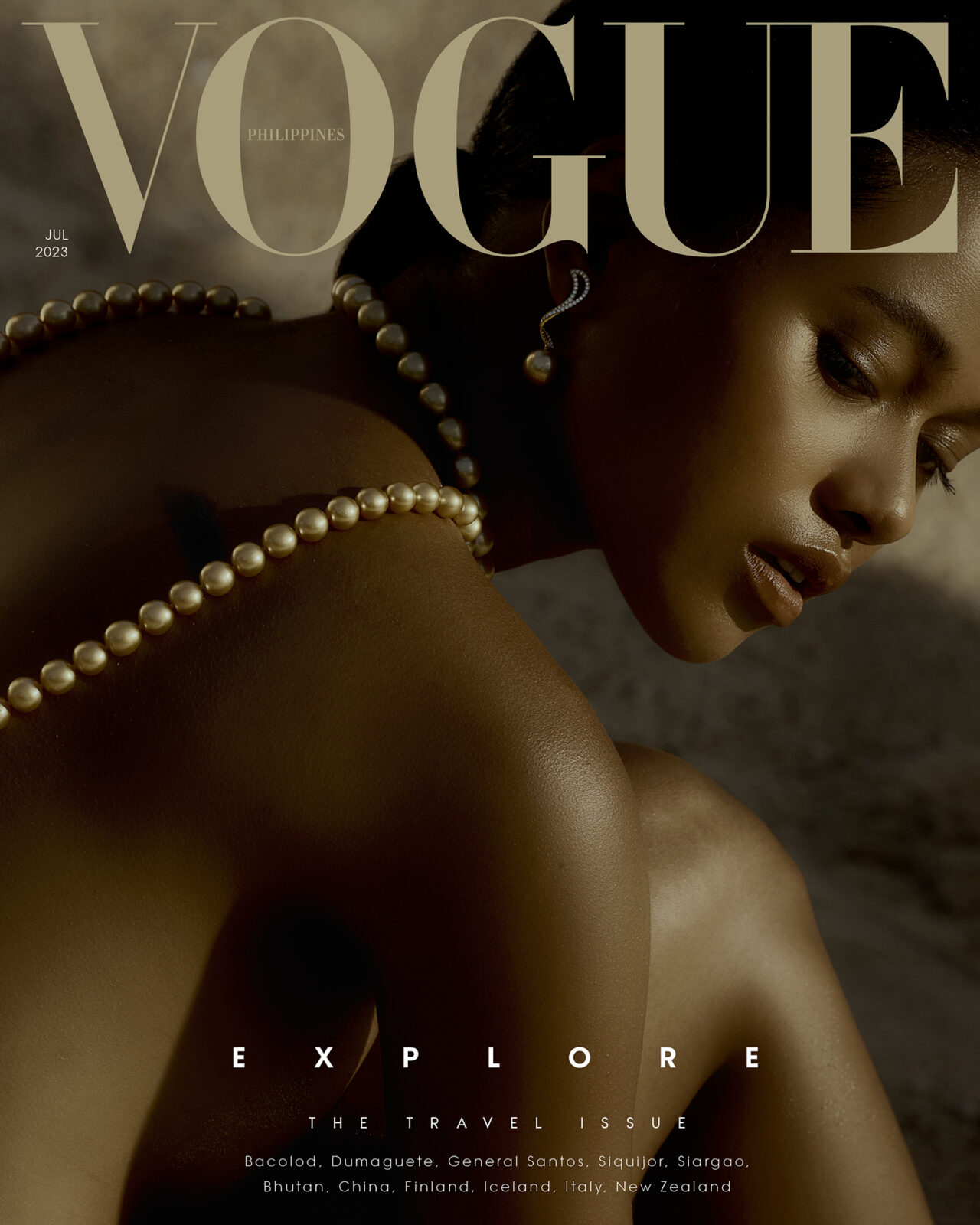

Photographed by Artu Nepomuceno.

Happiness is king in the country of Bhutan. Photographer Artu Nepomuceno recounts his journey through words and images.

On my last full day in Bhutan, I was recounting our adventures over breakfast with our tour guides Sonam Chophel and Sanjaa Thinle. Sonam is part owner of Bhutan Seriling Travels, the tour group that had organized our 10-day itinerary around the country. Sanjaa (pronounced Sang-gey) was the head guide and the serendipitous local champion we were searching for to continue the mission after we left.

This story has a handful of characters: Dave Lee, a New York-based businessman, musician, and father of two daughters; Paul Laca, an off-road biker and owner of a commercial salmon fishing vessel in Alaska; Corey Smith, an artist, snowboarder, and snowboard business owner; Panu Lucksom, a trekking specialist and the country head of Waves for Water India; and Jon Rose, retired international surfing champion and the founder of Waves for Water global, and the reason we all found ourselves in Bhutan in the first place.

The itinerary was straightforward: rent a handful of Royal Enfield Himalayas and drive from Phuentsholing through Paro, Thimphu, Phobjikha, Wangdue, and Bumthang. At every possible turn, the objective was to find communities that might need access to clean water, and provide them with filters. If they didn’t need them, then we would move on.

In 2009, Jon started the organization Waves for Water (W4W) as a reaction to a series of disasters that he witnessed. Traveling the world as a surfer, he found himself in Sumatra, Indonesia, when a 7.6 earthquake hit. This disaster took more than a thousand lives and displaced more than a hundred thousand people. As it happened, he had 10 water filters in his bag, and by default, became a first responder. Since then, Jon and the organization have made it their mission to provide access to clean drinking water, believing that it is a basic human right.

“Do what you love and help along the way,” is Jon’s philosophy. He believes that helping others would be most effective if it served as a driving force, consequence, and compliment to the things you were most passionate about.

Cave of wonders

First order of business: a trek up Tiger’s Nest. Locally known as Paro Taktsang, this monastery rests north of 10,000 feet above sea level on the side of a cliff in Paro district. One of the most recognizable sites of Bhutan, it is also one of the most sacred places in the country. Locals believe that the great Buddhist teacher Guru Rinpoche rode on the back of a flying tigress (who also was his wife) and found refuge in a cave where the monastery now rests.

The three to four hour one-way hike is a combination of grass, dry and wet rocks, stairs, and an uncomfortably steep climb. Foreigners wore the latest techwear and the best hiking shoes while the local guides wore formal leather shoes. With every step I lost a percentage of my breath and I was overtaken by active seniors and lazy kids. “Sandbagging” was the term Jon introduced to me as he handed me a protein bar: the process in which you fly a Filipino from a country averaging 1,500 feet above sea level, and on the first day, make him climb up to no less than 10,000 feet. It’s true that no good thing comes easy.

Upon hitting the nth slope, a breathtaking view of the monastery finally nests on the eyes. The photos do not lie: an architectural marvel clinging to the side of a cliff, with nothing but motionless clouds perfectly drawn in the background. At the viewing point, young monks chill on top of a boulder, welcoming hikers and studying these strange procession of visitors going through all the trouble to see the temple. But the view immediately becomes a memory, maybe as relief from a painful hike, or maybe the aspiration of something sacred. “You should see the temple during the winter season,” Sonam suggests.

After depositing our gadgets in a room of lockers, we entered the different shrines inside the temple, with freezing bare feet resting on freezing stone. Sanjaa provides us with a history lesson, and an intro to the values of Buddhism, and encourages us to pray, in the ways we personally understand and believe. In one of the shrines, I found a wooden floor with precious stones punched into them.

“Usually we recommend that the Tiger’s Nest is the last part of the trip, as the hike is not easy for many. Not to mention that Paro tends to be the last district visited,” our guide tells us as we make our way down, a journey filled with a dreadful anticipation of the soreness to come. Paro is currently the only international airport in Bhutan, and also known as one of the most dangerous airports in the world. To this date only eight pilots are qualified to land and take off from there.

Most days between districts were spent in transit; Sonam, Panu, and the four Americans were on their bikes while I was in the van with the luggage, extra motorcycle parts and tools, and the water filters. A lifelong history of motion sickness reminded me of my friendship with Bonamine; a pill a day allowed me to enjoy the rollercoaster of the winding roads the country had to offer. On some days we drove through zero visibility fog, on others we were inches from the edge of a full dropping cliff.

No hesitation or panic came from our driver, also named Sonam, who could have driven the whole route with his eyes closed. These daily car rides were filled with conversations and interesting experiences, from how the government handled Covid, to the means of income for the country, to how much they love and respect the current King. At one point we even made a stop to snack on wild strawberries growing on the side of the road.

Once upon a time, Bhutan’s source of income was agriculture, such as potatoes, apples, and oranges. One of their famous products was the Matsutake Mushroom, which they even have a festival for every mid-August. Today, they sell electricity to India through their hydro projects throughout the country as their primary source of income.

Tourism is a secondary source. Back in 2020, Bhutan ranked second in tourism in South Asia, generating around USD84 million. During the pandemic, the tourism sector was greatly hit and because borders were closed, locals reverted back to agriculture, although both Sanjaa and Sonam agreed that agriculture wasn’t going to make a comeback as profitable as tourism.

Bhutan has a well-structured system for tourism; all who choose to visit the country must specify the total number of days they are staying, and with that comes a USD200/day payment straight to the government. This payment goes to the development of the country and for the people, and the locals vouch for its effectiveness. But this system does not protect the country from abuse or poor manners: in 2019 an Indian influencer was arrested for standing on the roof of a temple.

At a lunch stop from Thimphu to Phobjika, Sonam made a call to an architect friend of his who had a project around the area and found out that there was a school less than an hour away. Through an uncomfortable drive through a rocky path, we parked ourselves at the site of more than a hundred children in dark blue uniforms with red trim, playing sports in a campus embraced by tall pine trees by the side of a steep valley. It felt like a scene straight out of the 1973 film Lost Horizon. Exchanged glances with Jon became the anchor point of our reality, securing the idea that we all saw the same thing.

Gratitude exercise

From the beginning of the trip, Jon made it a daily practice for us to talk about the things we experienced that we were grateful for. The first couple of sessions felt easy, but as the days passed it became harder to zone into singular experiences that felt most significant. Paul brought up the fact that what we had done each day was enough for us to go home and feel fulfilled. But every day, Bhutan was the gift that kept on giving. In one of those sessions, Corey pointed out that he hadn’t smiled this much in so long.

A few more initiatives were done. The last leg of our trip was to explore Bumthang, known as the New Zealand of Bhutan. As we entered the district, we crossed a fairly large town filled with apple trees. An ongoing festival was happening, which brought the locals out to the streets dressed in their best attire. As we passed, kids bowed at the sight of the van, and threw their hands out for the bikers to high five. The afternoon glow fell upon the youthful faces of the elderly as they watched their younger family members welcome their guests with so much hospitality, knowing full well that the receivers would never forget a special moment like that.

After spending the night at the Mountain Lodge in Bumthang, we took a drive to the base camp of Wangchuck Centennial National Park, the largest in Bhutan. There we met up with Kezang Dawa, the park’s head in water maintenance. The 4,914 square kilometer space hosts a diverse set of flora and fauna, one particularly special species being the snow leopard. With the rarity of what the park carries comes the need of protection, which over the years the Bhutanese government have been able to provide. The goal of the water filters for this particular area was to provide the protectors of the forest portable access to clean drinking water.

As Paul and Sanjaa did the demos for the water filters, in the distance came a bundle of sunshine named Kuenga Choden and her dog Ruffy. Kuenga is the eight year old daughter of Kezang, whose fearless attitude got her a free ride on one of the Himalayas. At the end of the demo, she and her dad brought us to what they call the Center of Happiness, a place that I would only assume to be a space that promotes happiness. True enough, the recreational space rests beside the calming sound of a river, with a courtyard of traditional architecture embracing gardens of dandelions and wild strawberries. It was in this space where I felt convinced that Bhutan knew how to design happiness.

In the 1970s, His Majesty Jigme Singye Wangchuck introduced the concept of Gross National Happiness in the belief that GDP does not adequately determine the happiness and well-being of the citizens. To quote the Bhutanese ancient legal code in 1629, “If the government cannot create happiness for its people, then there is no purpose for the government to exist.” By 2008 when Bhutan had embraced a democratic form of government, they further included the GNH into their constitution. The GNH is technically described as the “multidimensional development approach seeking to achieve a harmonious balance between material well-being and the spiritual, emotional, and cultural needs of society.”

Unforgettable moment

Back at the last breakfast, in between sips of coffee, while remembering the whole trip, I thought about my favorite moment.

It was on the third day of our trip, as we journeyed to the Gangtey Monastery from the Wangdue Eco Lodge, where we had stayed the night before. We made a pit stop at a temple along the road, where a curve of makeshift huts made of wood and tarp housed a group of women selling different handicrafts and souvenirs. A variety of intricate pieces were grabbing my attention: handwoven rugs, baby yak wool shoals, traditional clothing with interesting accents.

What caught my attention the most were the women themselves, beautiful and timeless, with just an energy and approachability I would only associate as a mother’s touch. Their eyes carried the curiosity of a child while the wrinkles on their skin connected their livelihood to one of hard work. After building a friendship with each of them I asked if I could photograph them together, with their favorite rug from their stores.

We moved, a site with the valley behind them. I snapped a handful of photographs. With their big smiles they thanked me, and asked if I could come back one day with prints for them to take home. Without hesitation I made that promise, and asked if they’d like to add to the souvenir by having solo portraits taken. One at a time, I photographed them with an attendance I haven’t felt from that many people in the span of my career.

As we drove away I asked Sanjaa more about these women, and I found that they spent most of their days selling novelties, which most probably were handmade by their parents. A particular rug I had bought was negotiated for by another tourist a few days before, but was respectfully declined as the sentimental value of their pieces were not worth a lower price tag.

I found that the only other means of income for these ladies was harvesting cordyceps, a type of parasitic fungi recently popularized in Pedro Pascal’s zombie apocalypse series The Last of Us. Every year from mid-May to the end of June, one member of each family in Bhutan is allowed to harvest cordyceps. This regulation done by the government provides an equal opportunity for all, as a mere 500g of top grade cordyceps can sell for thousands of dollars.

There is a common folk tale that taking a photograph also takes a piece of the subject’s soul. Over the years I’ve dealt with hesitations and apprehensions from people I had just met; who can blame them when such a belief is imprinted in their system. But Bhutan was the first country I had ever been to where I got a perfect streak, where not one single stranger felt even the slightest sense of worry with my camera pointed at them.

With this came a curiosity that drove me to ask about the foundations of the Bhutanese people. Sanjaa explained that it comes from a rooted core of nationalism, that with the birth of the GNH came the united front of representing Bhutan and the trust that the daily deposits tourists make to the government means everyone will benefit. It is in their culture to welcome tourists; the random bowing children on the roadside of any district, or the hospitality each lodge provided, to having their photograph taken. They look at the camera with love and life and pride, because they know the presence of a tourist means a better tomorrow for their country.

I’ve always been a believer in Jon Rose’s line of “do what you love and help along the way.” How every journey carries a certain gravity, and a personal mission that can only be achieved through an exchange of good will. Purity cultivates purity. But if there’s anything I took home from the Bhutan trip, it’s that beyond the giving, there is also so much that comes back to you.

The world can learn a thing or two from the humble and happy country of Bhutan.

To find out how to get involved with Waves for Water, visit wavesforwater.org.