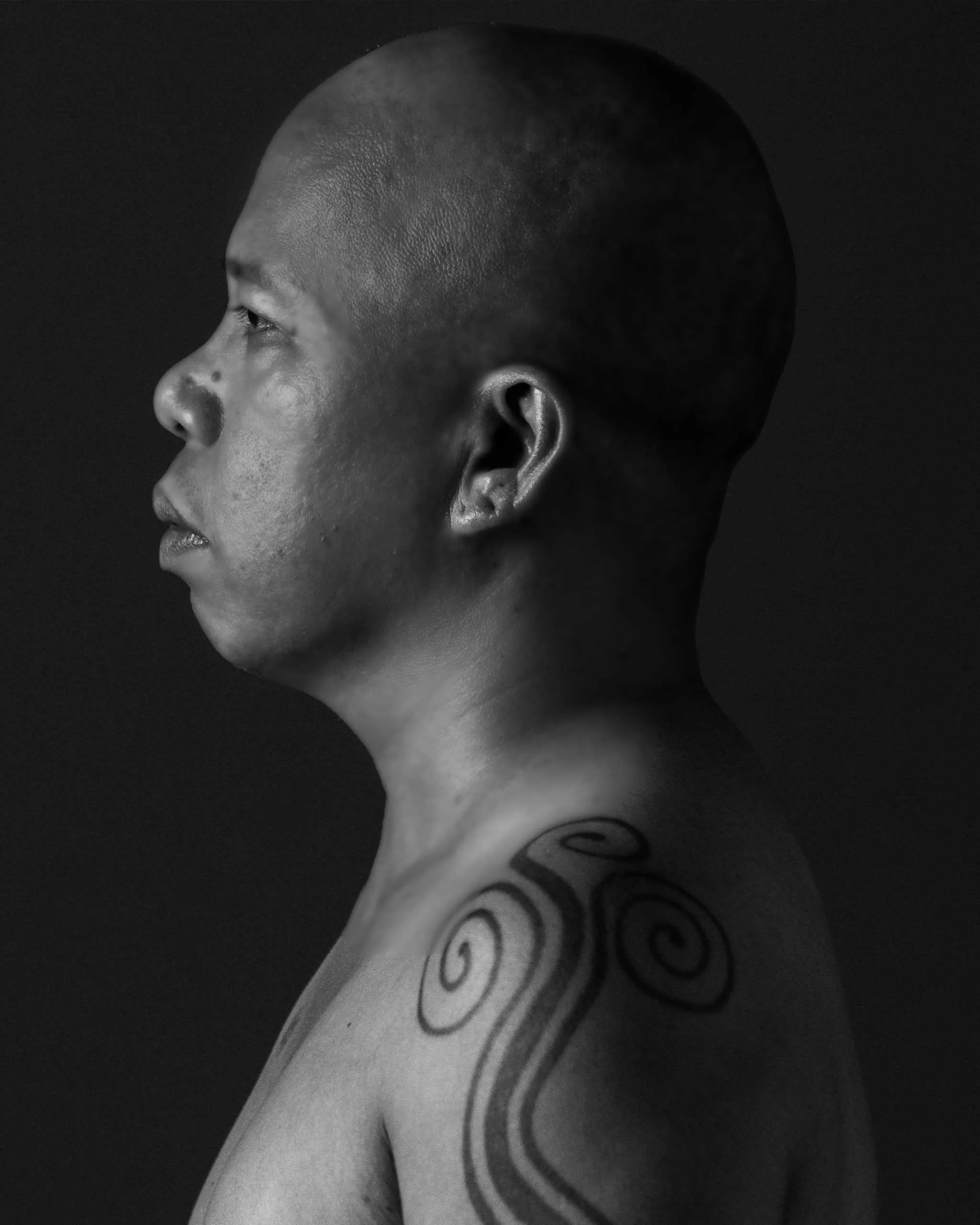

This image came from a set of “very significant portraits,” says photographer Jon Unson. “This was just after he got out of the hospital. He came to my studio and asked me to shoot him saying this was his chance for a new life and a new beginning.” Portrait by Jon Unson, from a 2016 photo session

Part Carlos Bulosan, part Fela Kuti, part Jean-Michel Basquiat, Errol “Budoy” Marabiles was the leading light of Cebu’s surging creative scene.

The window of time where Budoy’s life and mine intersected was all too short. It was well before his band Junior Kilat brought him fame. I was an instructor at the UP Cebu Fine Arts program and Budoy, just two years younger than me, was a student. Or at least I think he was a student. His actual matriculation status remained vague during my three-year stint, but he was one of those people floating around campus and at parties and the various ragamuffin beer-selling hangouts that dotted the periphery of the campus.

He was a joyous figure back then: witty, cool, the first person I knew who successfully grew dreads. He was also a remarkable athlete, which might seem a strange thing to say. A silky smooth softball player, a crafty pitcher, and a pool hall shark, Budoy Marabiles was a true natural, comfortable in his own skin. At that point, he wasn’t doing much music. He wasn’t part of a band. While his instinctive knack for percussive instruments made him a welcome, if occasional, sideman, he was thought of more as a gifted painter and conceptual artist. He had won a PLDT contest for the cover illustration of the yellow pages as well as two consecutive Jose Joya Awards, one with a painting he dashed off in an adrenaline-fuelled all-nighter, using materials borrowed from his fellow student Jessie Saclo. The payouts from those prizes would help keep at bay the demons of starvation and, shall we say, less-than-ideal sleeping arrangements while also funding his close reading of Dada and its foundations in absurdity, studies that would prove useful in later years.

No one had much of an inkling about what was ahead for him, but you just sensed it would be great. I wish I could find and post from the hours of clips I have of him, at the Viva Excon Bienale, at the Mindworks performance art festival, in the UP Fine Arts basement studios (dancing, smoking, drinking, cracking us all up) so you could see him in full. He had an ineffable quality about him. In a crowd of eccentrics, he cut a completely original figure.

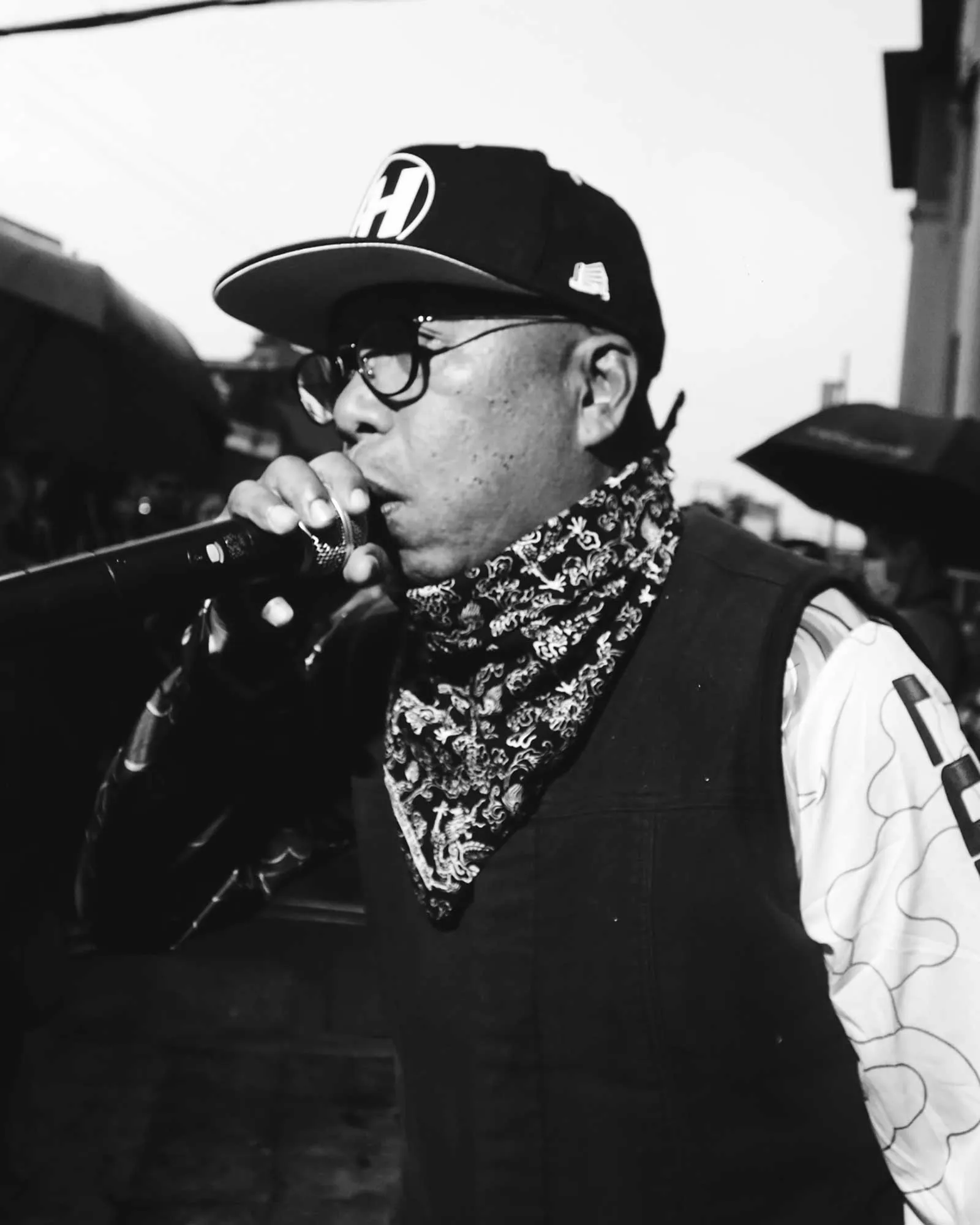

When I was living in Manhattan some years later I caught word of his success with Junior Kilat and it all made perfect sense. His videos in heavy rotation on MTV Asia, his Pinoy Big Brother stardom, his 2005 NU107 Song of the Year award for “Ako si M16,” this kind of recognition seemed written in the stars.

Of course, when I got a hold of the music, I was blown away. That James Brown horn section! The Bisaya idioms! The anarchic rapping! The fantastic beasts slithering through his lyrics! Friends would say in early performances he would just pick up a menu and read it over a reggae beat. Pure Dada. Tristan Tzara would be proud.

But even in those party people, holy goof days, he was framing his music to be more than just fodder for the radio. He derived the name of his band, after all, from the nom de guerre of the Cebuano Katipunero Leon Kilat. As his political and aesthetic consciousness rose, he penned in his 2016 song “Kawatan Ka,” released in the wake of the Pork Barrel scandal. It stands as both a harrowing lament for the crushing material realities of everyday life and a brutal takedown of the corrupt politicians whose actions make existence on these islands so much worse. The song’s compulsive, danceable qualities make it akin to Fela Kuti’s Kafkaesque Afrobeat masterpiece “Zombie” and it tracks that “Kawatan” has been taken up once again by young Bisayans as an angry sonic presence at protests, a ritual chant against all that is wrong in the halls of government.

One of the last times I saw him was in Cebu maybe eight or nine years ago when I was staying at my cousin’s apartment with my wife, who was his humanities professor at UP Cebu, and our two teenage sons. We were having a few beers on the deck overlooking the city lights with a few other friends. Budoy announced his arrival below us with the rumble of his Nighthawk 750. His dreads popped out of a knit bubble cap, and he was resplendent in a beaten-up leather jacket and jeans.

He was much the same: brilliant, observant, funny. I don’t remember exactly what we talked about but I was mostly just looking at him. It seemed impossible that this rockstar’s rockstar was once a teacher’s kid from a tiny island peopled by fisherfolk and subsistence farmers. I felt warmed by the light of his full-scale reinvention.

When he passed away, he and his business partner Dennis Pettersson were up to their necks in his latest project, a live music venue/recording studio/gallery called Sigbin Haus on the beaches of Santander. It was the kind of place that in the 90’s we wished existed somewhere, anywhere, within a hundred miles of Fuente Osmeña. I would hope the efforts of Dennis and Budoy’s many friends to sustain this space would succeed and the place would still be up and running many years from now. It would be as good a legacy as any for the Original Sigbin.

Sometimes, it seems that every notable Visayan artist fell somewhere within his orbit, not because of his fame or his talent or his celebrity, but because of his grace. He was the mentor to innumerable artists, deeply admired and loved by Cebu’s sprawling creative community as much for his generosity as for his preternatural genius. “I think he made a lot of Bisaya artists braver. As a self-styled Sigbin, the most important shape he shifted into was a key. He opened a lot of doors that we didn’t know existed,” said the artist, musician, and longtime friend of Budoy, Babbu Wenceslao. “He set a model for how young people might shape their lives. I like to think of him as a culture warrior, like Leon Kilat, in that he gave himself for his people,” reflected the artist Raymund Fernandez, his early mentor and Professor at UP Cebu.

But even for blessed, it all comes down to some kind of final act. To be felled by a heart attack at 54 while organizing a series of anti-corruption protests across Cebu island feels simultaneously unjust to those so deserving of the electorate’s wrath and so unfair to the world, to his fans, to the hopes we all held for whatever project, wacky or profound, he might draw us all to next. But his life was no tragedy.

His music will endure, his spirit will carry on. As Lola whispered to us, a Sigbin can never die. But to those of us who knew him, this moment hits a little harder, because in absorbing the shock of this horrible news, we all feel just how much the world is diminished.

The eldest of seven, Budoy is survived by his four sisters Joanna An M. Giray (52), Ivelym Irinco Marabiles (50), Caryl Naveres (47), and Ma. Almera Barsolaso (43), and two brothers, Marvin (48) and Kim (45). He had no children.

Jovi Juan is a filmmaker, technologist, and journalist living in London and Baguio. He taught installation, photography, and art history at the University of the Philippines, Cebu College from 1993-1995. He is the director, with Benjie Manuel, of the documentary Gónô Tmutul: Building a House of Stories; the designer and developer behind Mapping Philippine Material Culture; and the former Graphics Director of The Wall Street Journal. His latest project is Seven Mornings on Smallwood Lake.

- Sarai Believes That Music Is Its Own Kind of Language

- Filipino-Japanese Band Gliiico Rises With the New Wave of Indie Music

- The future of Philippine music is here: Billboard reintroduces itself to the Philippines

- Soul Searching: KZ Tandingan on Being a Child of Digos and Opening the World to Mindanao Music