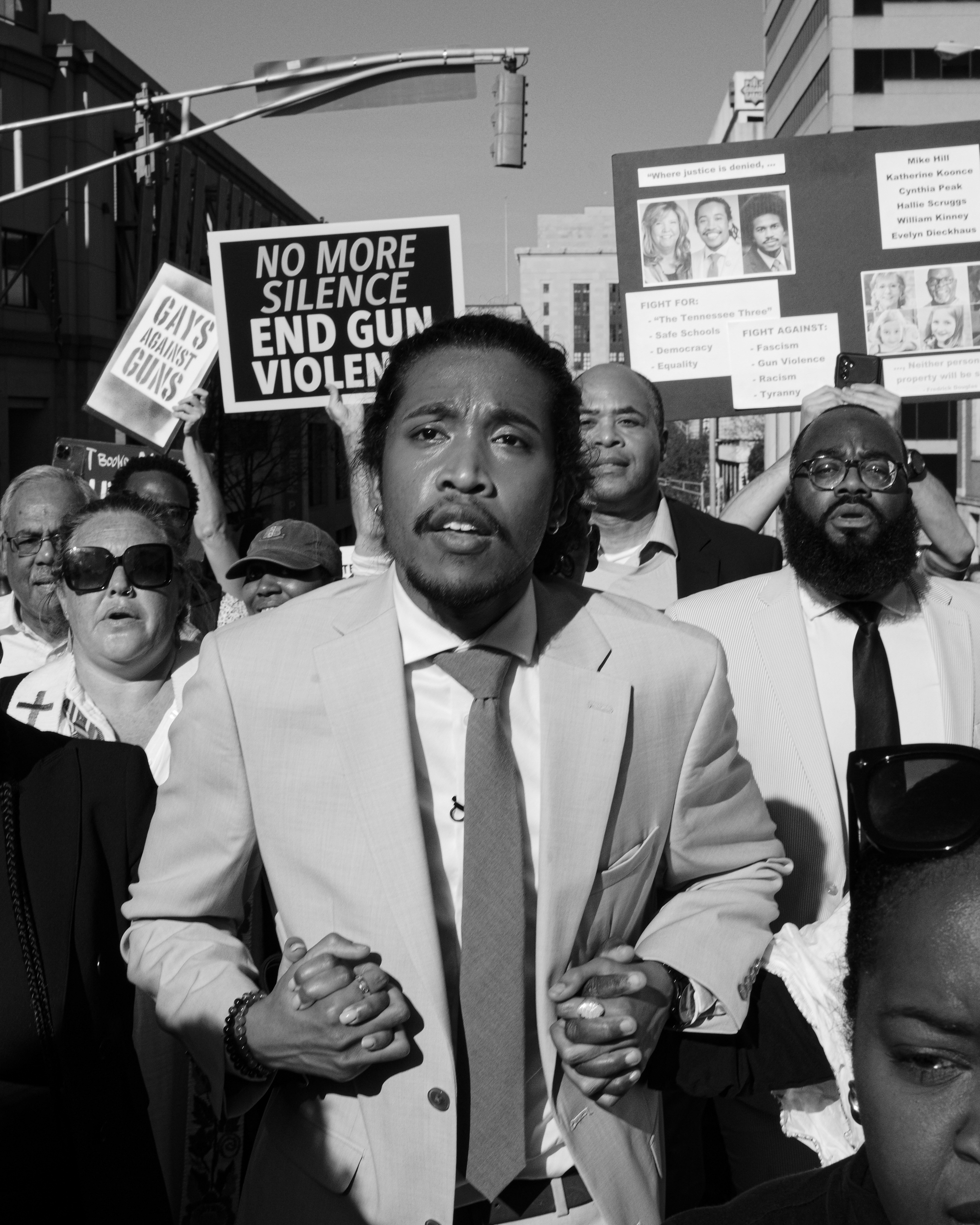

Photo by Ray Di Pietro

The Democratic legislator who became a national figure by protesting for gun control in the US talks to Vogue Philippines about finding solidarity in acts of resistance

“My lola walked in, and gasped,” says Representative Justin Jones of Tennessee. “She was so shocked. She started crying,” he continues as he describes the moment his grandmother met US President Joe Biden.

In the last three weeks, Rep. Justin Jones has bounced from channel to channel on American media and has become a symbol of hope for those longing for stricter gun control laws in the U.S. Though behind the images of him—in a white suit, earrings, and long hair pulled back in a ponytail—is a lola praying for him. “The President showed her his rosary because my lola had said that she’s always saying the rosary for my safety,” adds Jones, whose mother is Filipino.

Born in Oakland, California, Jones recalls hearing stories of the People Power Revolution from his lolo and lola. Inspired by these movements at a young age, the politician credits his grandparents for instilling the values of nonviolent resistance and the courage with which he speaks: ”My lola came here from the Philippines in the 1970s as a nurse, while my great grandfather came to California as one of the manongs in Delano picking grapes [leading to the labor movement spurred by the Delano Grape Strike].” Jones’ story is one that many Fil-Ams can see themselves in—reminding us that we belong here, even in the halls of power.

On April 6, Rep. Justin Jones, along with Rep. Justin Pearson, were expelled from Tennessee’s legislature for joining the youth-led demonstrations in protesting gun violence. Though in a turn of events, the attempt to silence dissenting voices in state congress only amplified Jones’ platform and catapulted the 27-year-old lawmaker onto the national stage. Almost overnight, clips of both Jones and Pearson speaking before their predominantly white male colleagues proliferated on news feeds, with spectators drawing similarities in both style and cadence to Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X from America’s Civil Rights movement of the ‘60s. The two Justins have since been reinstated and have come back to their state capital with the support of the President, Vice President, and the American youth.

Amid back-to-back engagements with constituents, journalists, and high-profile legislators, Jones tells Vogue Philippines, “I’m so sorry my camera is turned off. I’m not feeling well, but I didn’t want to miss this interview. I wanted to be sure to respond because this is part of who I am. It’s part of my ancestry, part of my current embodiment. I am grateful to be a part of the kapwa, to be a part of this community,” he says. “Our Filipino heritage is also one of resistance against injustice and of challenging systems that are meant to oppress and marginalize. It means a lot to connect with those in the Philippines and those in the Filipino diaspora.”

Three days before President Biden’s meeting with President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. at the White House, Rep. Justin Jones calls in from Washington D.C. to chat about the Philippines, the parallels between the U.S. and his motherland, and the unstoppable power of protest.

Can you talk more about your Filipino heritage?

My great-grandparents are from Cagayan. They’re Ibanag. My lola grew up in Pasig. I went to the Philippines for the first time in 2017, and I’ve spent the last few years learning more about our Filipino heritage, particularly on my lola’s side, our indigenous Ibanag culture.

How connected were you to the culture growing up? Can you recall any Filipino traditions from your childhood?

We did Simbang Gabi. I’m the oldest, so I’m the only grandchild who understands Tagalog. I don’t speak it that well, though. I grew up with my grandparents. In terms of the movement, my lolo told me about People Power in the Philippines when I was growing up. He told me about the nuns who kneeled in front of the tanks [on EDSA] during the democracy movements there. I grew up hearing those things. I remember sayings that my lola would tell me like: “Kapag binato ka ng bato, batuhin mo ng tinapay,” which is about responding in ways that are nonviolent. So culture has definitely been a part of my upbringing. My lola, mom, and cousins were at the White House with me on Monday.

You met with President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris in the Oval Office last Monday (April 24). What did it mean to you to be in that space of power? What did it mean to your family, who’s come a long way from the Philippines?

It was very emotional for my lola in particular. She worries a lot about me. I come from community organizing, and she always tells me to be safe and take care of myself all the time, while I’m in Tennessee and she’s in California. It was a beautiful moment to let my lola see that despite what we’re facing, the nation is standing with us in our struggle at the highest level. And really, across the nation, people have stood with us. It was just confirmation that we are on the right side of history and that our ancestors and creator are with us on this struggle to uplift multiracial democracy in a community where all voices—regardless of race, immigration status, sexuality, or economics—are affirmed of their dignity and respect. It was beautiful to see that.

Switching gears a bit, many of those most inspired by you are under the voting age of 18. Besides making it to the polls, what can young people do to enact change on a legislative level?

Our actions that have led to this point were inspired by the young people, by middle schoolers and high schoolers—many of whom can’t vote yet but came to our state capital and showed up by the thousands to lift up the movement. They want to feel safe in schools. They want to challenge the system that proliferates guns, which is a very uniquely American problem in our nation. I think we’re the only Western nation where mass shootings at schools keep happening. We must lift the lives of the students over the profit of the gun industry, so I think young people should step up into their power.

If they were not powerful, they would not be trying so hard to stop us. Looking at the intersection of issues, like fighting gun violence, democracy, the economy, and climate issue—which I know is impacting the Philippines and feeling the climate catastrophe that we’re in right now—young people should continue to be present in these spaces. We don’t have to wait for an election. We don’t have to wait until the voting age to put pressure on these systems. We can do it through nonviolent community organizing. That’s how I got my start. I was 17 and in high school doing community organizing work.

In a recent interview, you shared that, “Voices like ours are not welcome there. In committee, our microphones are shut off; we’re not allowed to speak on the floor usually. That’s why we went to the well, to be heard.” Many of us with similar backgrounds to yours enter these predominantly white institutions and feel similar to how you did in the legislature. What is your advice for taking up space and asserting our voices within these institutions?

To be our authentic selves. I go into a body that’s predominantly white men. From the day I first walked in, I was told to assimilate. But I go into the legislature with long hair and earrings because, for me, that is a connection to my ancestors. I keep [this look] to subvert the norm of what they expect us to be. Another member told me once, ‘You should be grateful to be here. You should be one of us.’ But we’re not there to become the system that we’re fighting. We’re there to represent this creative and disruptive energy that is about centering voices that have been pushed to the margins for so long. In these spaces, it’s good to remember that these are my colleagues and not the people who sent me there.

I always keep in mind who I’m standing for when I fight. The people [in the legislature] may be hostile, dismissive, and patronizing, but I speak with the boldness of my district that gave me the mandate to go there and fight for them. There’s a saying by Maya Angelou that I keep in mind: “I come as one, but I stand as 10,000.”

My district is the most multiracial district in Tennessee. It’s a largely immigrant district. It’s Black. It’s brown. At the high school in my district, there are 62 languages that are spoken, so I center that experience that is unique and needs to be heard. On the other side of the aisle, my colleagues represent districts that aren’t like that. When they’re passing these laws attacking immigrants or are overtly racist as they often are, I have no choice but to speak up. If I don’t, who’ll speak for the 78,000 I represent? It’s the clarity to know that our voices are needed there and that we are not standing alone.

You’ve become an overnight figure in the power of youth and protest against anti-democratic forces holding so much power in society. What have you learned from your recent demonstrations of bravery?

Their overreaction and their attempt to silence our movement have confirmed and awakened this consciousness, this reality that we are facing authoritarian forces that are actively trying to take us backward. It galvanized our movement to say that this is an emergency that we’re facing.

I learned that movements are more powerful than temporary political power. My colleagues who expelled me thought that they were all-powerful, that they would expel us and be done. But we showed them that when you come for one of us, you come for all of us. That’s why three days later, I got reinstated.

It’s been so important [to know] that we have not stood alone in this multiracial, multigenerational, global movement. The day after we were expelled, the vice president changed her plans and made an emergency trip to Nashville to stand with us. In a state like Tennessee, people said it was almost impossible to be a progressive voice, but we’re showing that all across the nation, courage can be contagious. Small acts of dignity and small acts of courage can inspire others to act.

There are so many lessons, but I’ve been so grateful, particularly to the young people who’ve reached out. If you look at the pictures of me on the floor with the megaphone, I was holding a sign that was made by a child in Nashville. I was trying to bring the voices of young people to the floor of the house when we were being silenced.

Who are some Filipino figures you look up to?

The conditions and the fight for democracy in the Philippines are very personal and close to my heart on all levels, from seeing indigenous communities resisting this placement and the taking of their land to seeing the journalists who are facing threats. So I’ve kept up a lot with Maria Ressa. She’s an inspiration. Another political inspiration for me is Miriam Defensor Santiago, who was in the international criminal court and the Filipino government. I keep a quote in my office by Ninoy Aquino that says: “I’d rather die a meaningful death than live a meaningless life.”

Looking at what’s going on in the Philippines, I’m hopeful to see these young people leading these movements for democracy, for the environment, and for human rights. I’ll continue to uplift their struggle, and hopefully, we’ll be able to be in the Philippines soon to stand with them.

You’re from California, where there is a history of Filipinos engaging in nonviolent protests against unfair working conditions in the fields. One example is the Delano Grape Grake in the late 1960s when Larry Itliong and Cesar Chavez teamed up to strike for better working conditions. Moving from California to Tennessee, what have you noticed about the identity of Filipino-Americans in our history and our contemporary culture?

Looking at the role that Filipino-Americans have played in the labor movement and the fight for dignified working conditions, that is the legacy of which we are a part. Even looking at Civil Rights leaders, like [Supreme Court Justice] Thurgood Marshall—his wife was a Filipino-American activist. I was at the Black Caucus here in Washington, and I met with Congressman Bobby Scott, who is Black and Filipino. We are connected nationwide with Filipino-Americans pushing forward.

I’ve been researching W.E.B. Dubois, who is a prolific scholar and activist in America. It’s so powerful to see his acts of writing that are in solidarity with the Philippines, which at the time was a territory. He talked about how Black Americans are so familiar with oppression and injustice that we have the sensitivity [to empathize with] and stand up in solidarity with the Philippines, with Puerto Rico, and these territories of the United States. Throughout history, our movements have been in solidarity with each other. Our movements for liberation and justice in the United States with the Black Americans and the Filipinos have been in solidarity. This is not new. It’s been a part of our very resistance throughout generations.

There’s an interesting history of Black and Asian solidarity. One example is Malcolm X and activist Yuri Kochiyama. Though today, there’s still a lot of anti-Blackness in Asian cultures. In the US, where many immigrant communities come together, how can we overcome those feelings of disunity and really come together to dismantle white supremacy? In other words, how can we continue that legacy of Black and Asian solidarity that we’ve witnessed during the Civil Rights movement?

It’s to not allow these narratives of divide and conquer to become dominant in our communities. Growing up Black and Filipino, I heard the colorism and anti-Blackness. This is something we’re familiar with, but we have to push against them and let people know our liberation is connected and inseparable from each other. These forces that seek to pit us against each other have none of our interests at heart. Our generation is a bit more intersectional and more aware of these things and is pushing back. I remember during the Black Lives Matter protests, we saw Black and Asians in solidarity marches. That’s been so critical to see because we face the same force of white supremacy that wants all of us to be ostracized and marginalized in silence.

And what about the older generation?

It was hard growing up and hearing some anti-Black comments, like being called itim. That’s all very harmful, but I do have some grace in some regard for the older generation who saw this as survival, but it’s also trauma. Those types of comments are rooted in trauma, rooted in this false sense of security that they thought would come with assimilation, which we know is false. We know that [assimilation] won’t protect our people.

I see a lot of Filipino-Americans trying to learn more about their indigenous culture. For me, I’m connected with the Center for Babaylan Studies with Tita Leny Strobel, who’s been critical in my journey. We’re seeing this resistance to white supremacy that wants all of us to shrink and silence ourselves and fight each other, so we’re distracted from the real opponent, which is white supremacy, economic exploitation, misogyny, homophobia, and transphobia.

Many more young Filipinos will know you’re Filipino once this feature comes out. What’s one takeaway message you’d like the Pinoy youth to learn as a fellow young person in the office?

Step into this lineage of liberation, which we are a part of. Know that we come from fighters. We are fighters, who resisted the colonization of Spain, Japan, and the imperialism of the United States. We come from people who so many have tried to conquer, and yet, we still have been able to hold on to our culture. We even continue to tap into our culture as a form of resiliency. With every movement throughout history, you’ve seen young people at the forefront. It’s our time again. We are voices that are needed now—Gen Z, particularly. These are the voices that should step into these roles and speak to the power because it is our very future on the line.