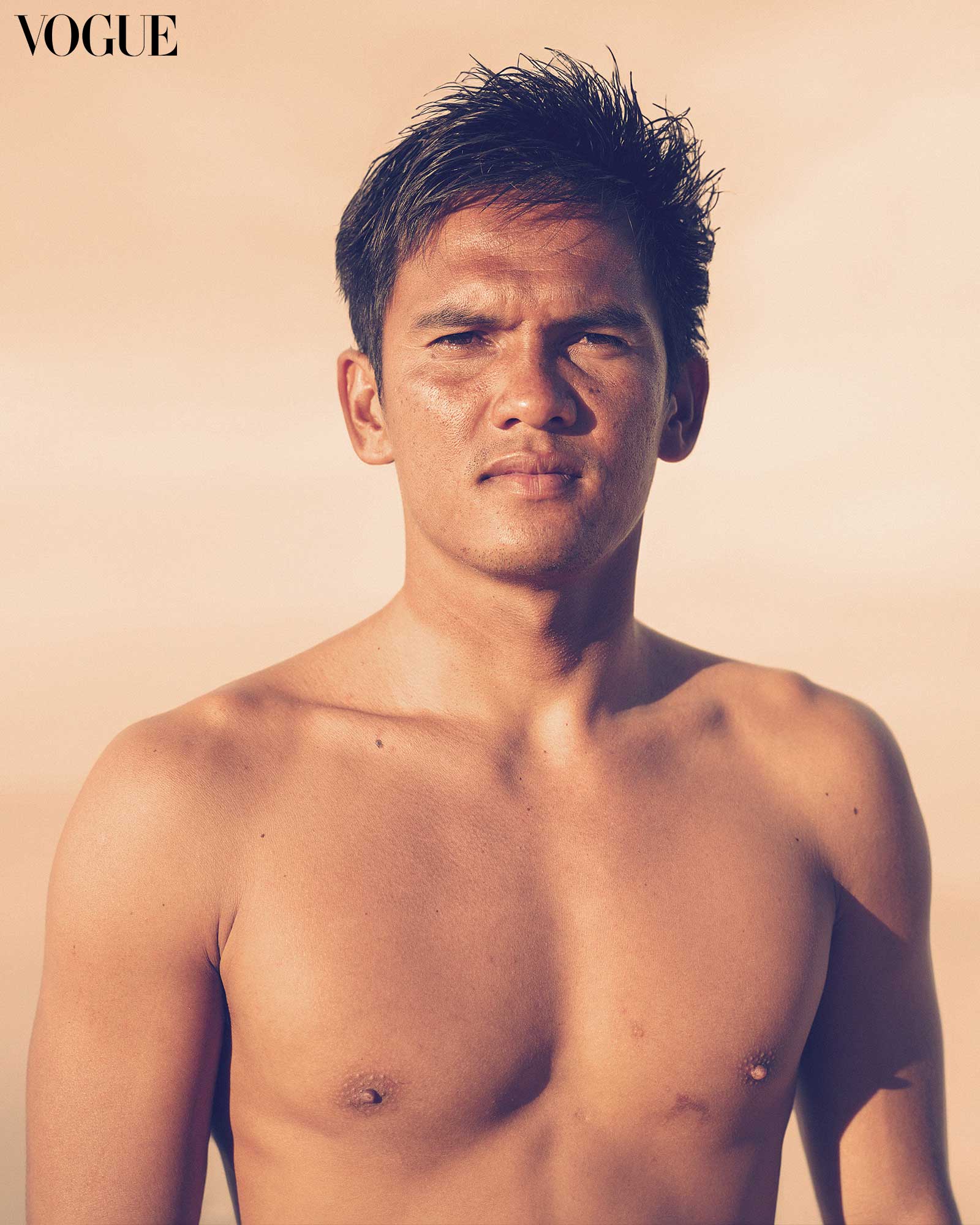

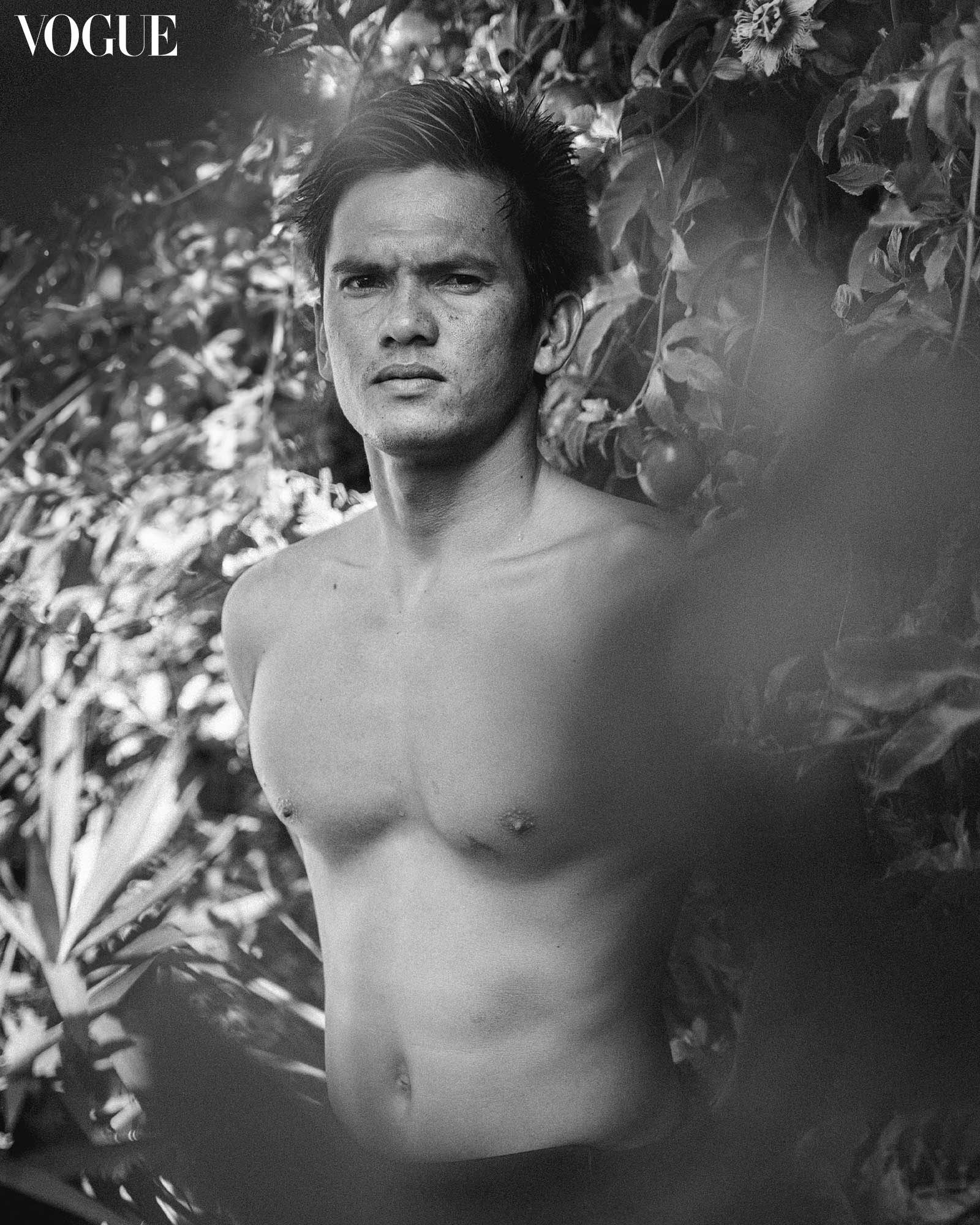

Photographed by Steve Tirona for the July 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines.

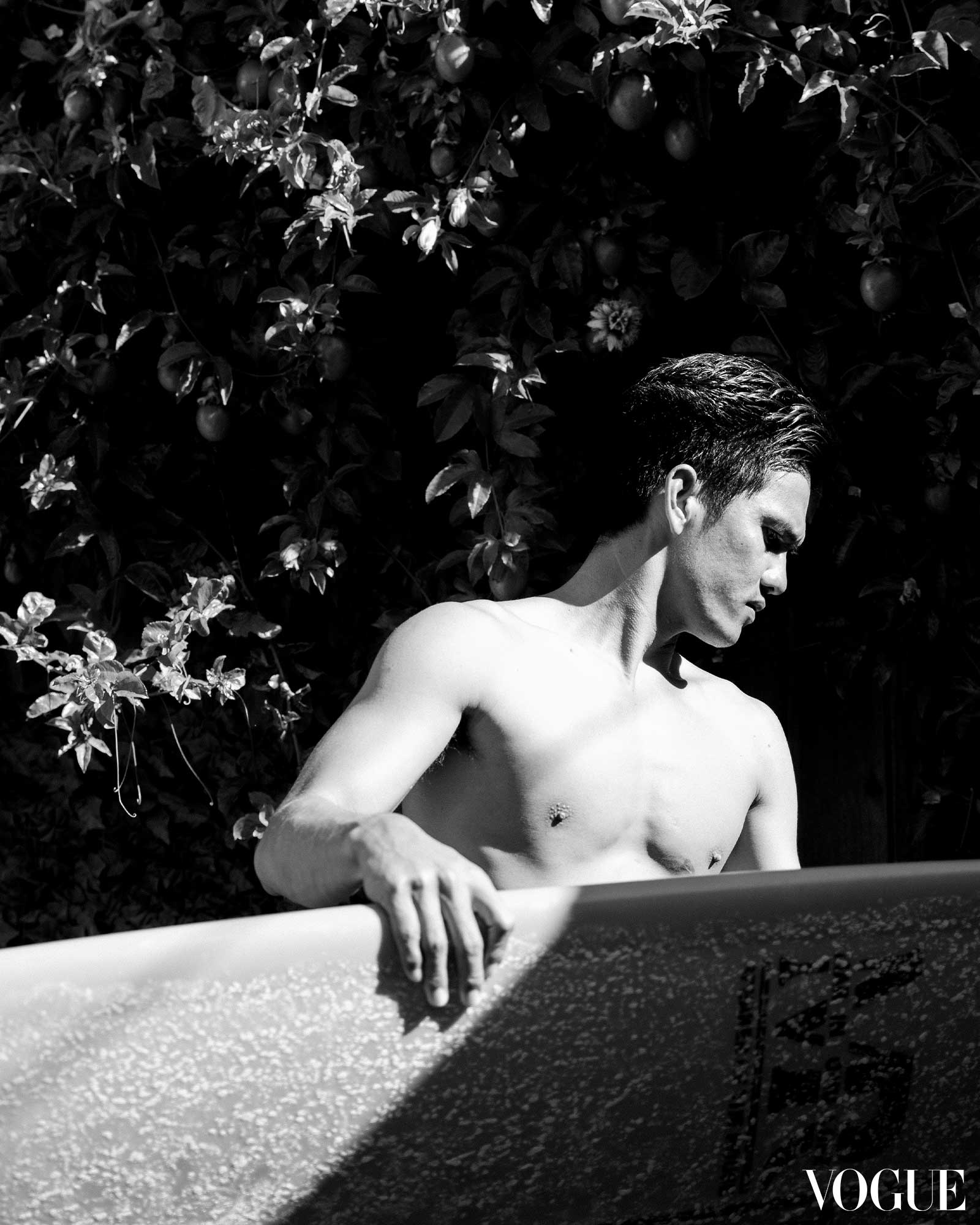

Photographed by Steve Tirona for the July 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines.

Surfer Jay-R Esquivel has the world looking at the story of Filipinos in the sport, and the town where it blossomed.

Even though it’s Jay-R’s first time in America, the scene he’s making at Huntington Beach looks more like a homecoming. It’s the first leg of the 2023 WSL World Longboard Tour. At 27 years old, Rogelio “Jay-R” Esquivel from Barangay Urbiztondo, San Juan, La Union, is the first Filipino surfer to qualify for the chance to become a world champion.

Naturally, Filipinos have taken over the California beach. The sea breeze carries the smell of pork barbecue across the water; people have set up tents and are handing heaping plates of food to anyone passing by, or a shot of rum, if you know who to ask. People in the crowd are sporting matching t-shirts printed with Jay-R’s last name and the number 15; borrowing from basketball, his fans have turned his birthday, July 15, into his unofficial jersey number. It looks like a reunion, and for many of these barkadas, it is. One guy has traveled from as far as Chicago, and some people are waving Philippine flags, the yellow, red, white, and blue shining bright against the northern hemisphere sky. After having been accosted with lumpia, one of the competition judges jokes that Jay-R has brought his whole village with him. Afterward, Jay-R posts on IG, thanking #barangayHB for making him feel at home in a foreign land.

At first, the idea of getting in the water alongside his heroes made him nervous. As a kid he watched the top pros travel the world on tours just like this one, poring over their photos in surf magazines, studying their surfing on YouTube. “Iba talaga yung feeling na kalaban mo sila sa isang heat,” he admits. [It’s a special feeling to compete against them in a heat.]

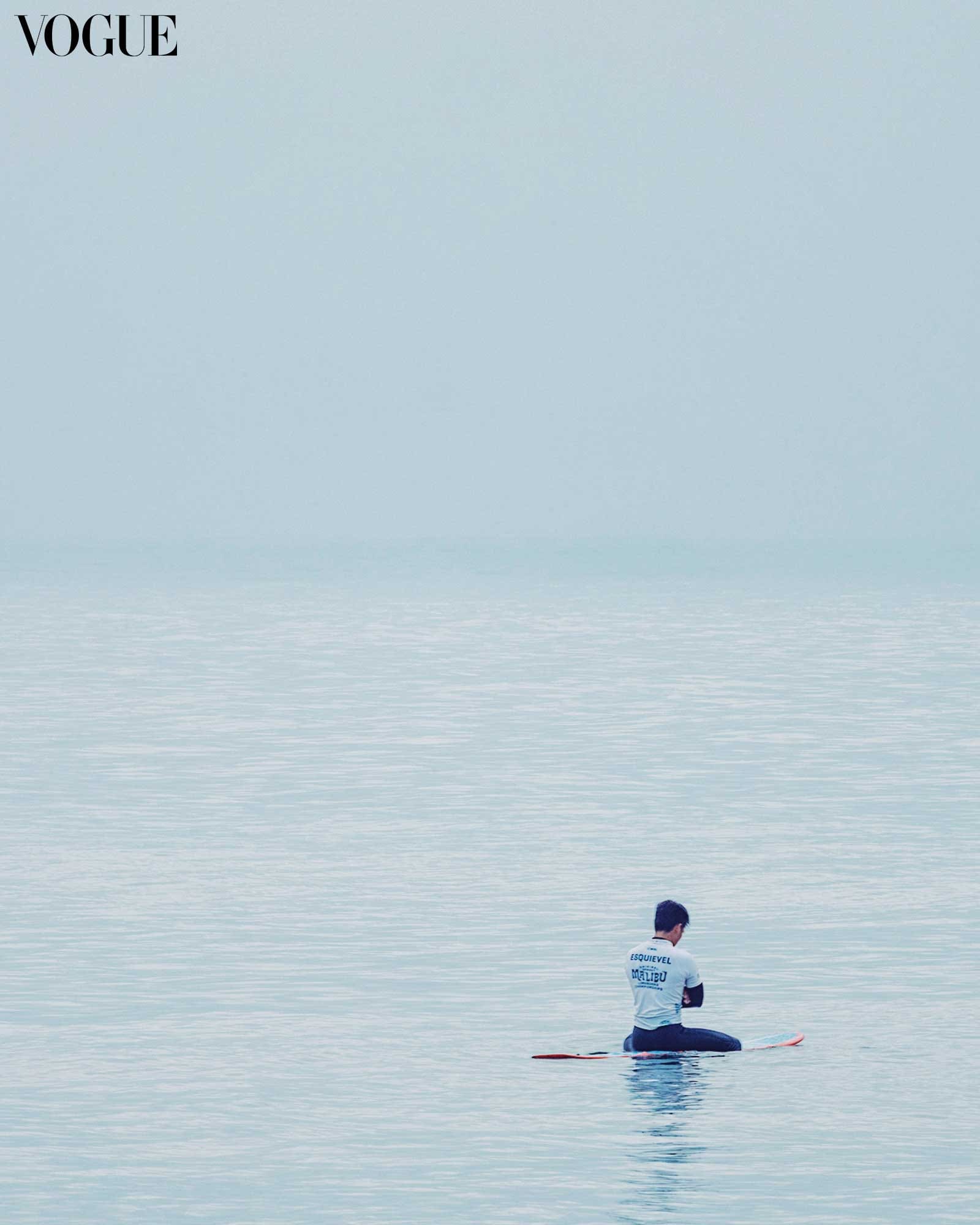

Thankfully, Jay-R had arrived in California a couple weeks early to practice. He spent a good amount of time doing nothing but watch: the waves, the other competitors. And he realized that they were good, but it wasn’t like every wave they surfed was perfect. In other words, he had a chance. Because the very nature of surfing is an endless dance between control and the lack of it. Even for those who’ve known the ocean their whole lives, every wave is different, demanding that we meet it anew. “Kahit mas angat yung laro nila sa atin, may chance pa rin,” he continues. “Nakita namin dun na kaya naman palang makipagsabayan sa kanila.” [Even if their level of play exceeded ours, there was still a chance. We saw that we could also keep up with them.]

Today, the conditions at Huntington Beach aren’t perfect. The wind has picked up, roughing up the surface of the waves, which build up to a formidable wall before crashing heavily onto the sandbar. These are the kind of waves that sand-bottom surf spots are known for, powerful yet unorganized, shifting with the sands and tides. The kind of waves Jay-R grew up surfing.

As soon as he gets in the water, everything else fades away, he says, leaving only excitement. During his first heat, he starts strong and holds onto the lead, cross-stepping across his longboard with the fluid yet measured movements of a tightrope walker. He seeks out pockets where vertical lift meets downward crash, so that he can perch at the very tip of his surfboard, 10 toes over the nose. The hang 10 is the ultimate expression of longboard surfing, where one’s reading and riding of waves creates a sense of flow so tuned in that it approaches stillness. The chaos assembles into a moment of perfection: Jay-R levitates, his hands hanging loosely at his sides.

The way the beach explodes in cheers every time he catches a wave, it’s as if Jay-R’s already won, and in a lot of ways, he has. Just as a wave travels thousands of kilometers to reach land, Jay-R being here, in California, surfing the cold waters of the opposite end of the Pacific Ocean, is a chapter in a story that began long before he ever boarded an airplane. And it won’t end here, either. Because as much as this moment is Jay-R’s, representing his coming of age as a competitive surfer, it also belongs to his community, who over the course of three generations, have uplifted themselves through the sport of surfing.

“My Kuya Poks taught me [how to surf]. In the beginning, he’d just push me onto waves, but when I finally learned how, I got so addicted to surfing I would just go out on my own. Then I was surfing all day, every day.”

Jay-R is a second-generation surfer from Urbiztondo, a stretch of beach alongside the national highway on the outskirts of San Juan, La Union, which has transformed over the last couple decades into the unlikely tourist destination known as Elyu.

“Start ako mag-surf mga six or seven years old, si Kuya ko Poks yung nagturo sakin. Nang una pina-push-push lang niya ako sa alon, tapos hanggang sa natuto na ako, siempre sobrang na-addict na ako ng todo, nagsasarili lang ako—surf lang ng surf every day,” he shares. [I started surfing when I was six or seven years old, my Kuya Poks taught me. In the beginning, he’d just push me onto waves, but when I finally learned how, I got so addicted to surfing I would just go out on my own. Then I was surfing all day, every day.]

Kuya Poks, or Ronnie Esquivel, was Jay-R’s older brother, a surfing icon who managed to become a competitive surfer despite having been born with only one fully formed leg. These were the early days of Philippine surfing, when the scene was a scattering of surf spots, each with their own community of local surfers, and visited regularly by a core group of weekend warriors from urban areas like Manila and Cebu.

Life was hard for the Esquivels, growing up. Their mom passed away when Jay-R was in the second grade; their dad did odd construction jobs, but was mostly out of work. Sometimes the power would go out; other times there wasn’t enough to eat. Their neighbors, like Kuya Nonoy and Ate Lanie, helped however they could, but it was Poks who ended up taking care of the family, using his prize money from surf competitions and the sponsorships he picked up. “Si Kuya ko, siya lahat. Parang siya yung pinaka-Dad namin,” remembers Jay-R. “Siguro hindi napapansin ng iba, pero bago kami mag-surf binibigay niya ng advice kung anong mga dapat gawin.”[My kuya took care of everything. He was like our dad. Other people might not have noticed it, but every time we headed out to surf he’d give me advice on what to do.] He taught him to always catch the first wave of the heat during a competition, to start strong.

Tragically, Poks died young, of cardiac arrest at the age of 27. He had lived the way he surfed, and so left his younger brother with the most important lesson of all. “Hindi niya inisip yung disability niya magkaka-affect sa kanya sa pakikipagsabayan sa mga locals. Parang normal din yung isip niya na kaya niyang lumaban.” [He didn’t think about how his disability affected his ability to keep up with the other locals.] Day after day, Poks would stick his crutch in the sand, and paddle out to sea. “Tiwala sa sarili talaga pinaka number one,” says Jay-R. [Trusting in yourself, that’s number one.]

As a kid, Jay-R was small for his age and quiet, almost painfully shy. But everyone, especially the surf photographers documenting the scene, could see he had something, even then. Kage Gozun, a photographer and writer from Manila, recalls the time she chaperoned Jay-R and a group of La Union groms—surfer kids—to join the Aurora Surfing Cup in Baler. They shared a rented kubo and “All the kids had an assigned task, except Jay-R. He was so small that, to even reach the kitchen sink, he had to stand on a stool,” she shares.

“But Jay-R decided he wanted to pitch in,” Kage continues, “and assigned himself the task of making the beds every morning. He probably doesn’t remember this because he was so young. He also didn’t announce that he was going to do this. He just did it.”

In 2010, he won a trip to compete at the Billabong Occy Grom Comp, his first international event. He was too young to travel alone, so he was escorted by Luke Landrigan, one of the head coaches of the Philippine team, and Poks’ best friend since childhood. “He joined the division for kids under 16, and he won it,” Luke remembers. “Then he joined the men’s open, and he got second. Men’s open!” Jay-R was 13 years old. “Next thing you know,” he laughs, shaking his head, “he’s eighth in the world.” He says that Jay-R’s not just physically talented, he’s good with numbers, too. “I’ll ask him about yung nakalaban niya four years ago, sa heat niya sa semi-finals, kung ano yung score, he knows.” [I’ll ask him about who he competed against four years ago, during the semi-finals of a particular competition, and he’ll even remember the score.]

“Of course,” he adds, “what people are seeing is the outcome, but they don’t really see the process.”

“Trusting in yourself, that’s number one.”

Devotees of surfing like to say that it isn’t a sport, it’s a lifestyle. But for many communities, such as Jay-R’s, it’s a livelihood, too. Back in the ’80s, the only establishment for miles was a girly bar named Dama de Noche; some of the locals still remember their parents working as bouncers or selling barbecue outside. They’ll be the first to tell you that Urbiztondo used to be the kind of place where buses were scared to stop; that they’d sometimes find dead bodies thrown into the empty fields—although I could never tell if that last one was just a story used to scare outsiders.

And then surfers started showing up. “For four dollars, you could buy a publication through Surfer Magazine that would show you like 30 spots on Luzon,” shares Stefan Chico La Grow, an engineer and US air force retiree who’s been coming back to Elyu since 1984. “I remember [the author] wrote, ‘Mona Liza Point sticks out into the South China Sea, just enough to be a magnet and catch all swells.” In 1997, Japanese surfboard shaper Kazuo Akinaga, more affectionately known as “Aki San,” organized the first surf competition, in which Poks and Luke participated in as groms. Gradually, Urbiztondo reorganized itself around surfing: surf lessons and tourism replaced fishing and construction as the main sources of livelihood; the rice fields and carabaos changed into family-run eateries and accommodations; and the community came together to form the La Union Surf Club (LUSC).

Surfing offered not just a way out for one person, but a way forward for the entire community. To actually build that path, however, took the accumulated experience of the first generation of surfers, who had seen how it had gone, so they could shape where it could possibly go.

“During our time, dream lang namin ’to,” shares Ian Saguan, president of LUSC and head coach for the Elyu Surf Team, his voice hoarse and happy with disbelief. “Hindi talaga namin inasahan na mangyayari [ito] sa Philippine surfing. Sinabi namin, ‘Wala, malayo [pa] ang world-level.’” [Back in the day, in our time, this was just a dream. We didn’t expect that this would ever happen in Philippine surfing. We told ourselves that we were so far from being world class.]

“In the old days, everyone would drink the night before a competition, and then wake up at 5 A.M. to ‘O, heat mo na,’” Luke adds, only half-joking. His Aussie dad and Filipina mom put up one of the oldest surf resorts in Urbiztondo, San Juan Surf Camp, and at 41 he’s still one of the top surfers in the country, although he’s more focused on progressing the sport as a whole these days. He recounts how most competitions were one-off events, failing to provide the cumulative progression needed to turn surfing into a professional career. Back then, surfboards were expensive and hard to come by, and financial support even more so. So the surfers who won were usually those who could afford equipment, or were lucky to nab the rare sponsorship that actually provided for boards.

“It was like, what’s next?” says Luke. Without much of a future in competition, pros often had no choice but to teach surf lessons, or start small businesses. Before Ian went to Japan to compete on their circuit, he remembers being so desperate for equipment in the early days that he stole the surfboard sign of Luke’s dad’s resort; lacking proper surfboard wax, he used candle wax to give old board grip. “Luke remembers this,” he laughs.

Finally, a few veteran surfers from around the country, including Mike Oida, a Fil-Am based in Pagudpud; Bjorn Pabon, based in Bicol; Manuel Melindo, from Siargao; and Luke himself, got together to professionalize the sport. In 2007, they helped to form the United Philippine Surfing Association (UPSA), legitimizing surfing as a national sport so that Filipino surfers could compete in World Games. Then in 2017, they launched the Philippine Surf Championship Tour (PCST), which Luke and Mike ran for a few years before it was taken over by UPSA and renamed the Pilipinas Surfing Nationals. “We made it so that surfers were running it,” says Luke, so that it would be more “core,” short for hardcore. They would build for a younger generation of surfers what they would have wanted for themselves.

The PCST succeeded where previous attempts at a national championship had come up short (RIP, Philippine Surfing Circuit); by standardizing judging, their competitions could be recognized by the International Surfing Association (ISA), thereby creating a gateway between Philippine surfing and the world. Surf spots around the country can now hold nationally and internationally accredited events, and local surfers who win the PCST automatically become a member of the national team, which qualifies them to represent the country internationally. It also opened the door to institutional backing; on top of the national team being supported by the Philippine Sports Commision, one of UPSA’s directors, Ilocos Sur First District Representative Ronald Singson, a hardcore surfer himself, lobbied in congress for years, which is how Jay-R got the funding to go on tour.

Rather than rely on the model of importing diaspora athletes to play on our national teams, the national tour is shaping world-class competitors by strengthening surfing at the grassroots level; the fact that the surfers and coaches on the national team come from all over the Philippines is evidence of this. And how did its original founders know how to do all this? They learned from those who had gone before them: the Indonesian organization known today as the Asian Surf Cooperative (ASC), whom they met in Bali, 2008, at the very first Asian Beach Games. “Wow, everything was so organized. They had their proper judging, their computer system,” recalls Luke. “The Indo crew helped us get our start… we really look at them as our big brother.”

“[Jay-R has] an unwavering commitment, but sometimes that isn’t enough. Fortunately [he] had people that believed in and nurtured him,” shares Tim Hain, a Bali-based photographer and ASC organizer. He reiterates how, over the years, various organizations have “created pathways for him to train and prove himself ready to jump on the world stage.”

“If all those people didn’t organize those competitions, slowly, slowly, slowly, na nanakilala ng surfing spot [nila] (until their surf spots became known), none of this would have happened,” affirms Luke. The more competitions, the more exposure, the more tourism, the more support, the more chances to level up. With the professionalization of the sport, surfing became a vehicle for transcendence.

“From the beginning, this was our mindset, that the whole team would support whoever among us levels up.”

Back in Huntington Beach, Jay-R wins this heat, and the next. Then, he loses to Kaniela “Kani Tsunami” Stewart from Hawaii in the quarterfinals. Finishing in third place, he advances to the next stop on the tour.

Kani Tsunami will go on to win the competition, but before he does that, and just after their heat is over, he hoists Jay-R on his shoulder. Jay-R is beaming with his whole body, and the sound of applause washes over them, both. The glory is palpable, the zeal infectious. Maybe this is why Pinoys make such devoted sports fans: when you know how stacked the odds against you are, it feels so good to watch one of your own finally win. The joy is deeper than the single-note high of victory, and more basic than an overeager attempt at Pinoy pride; it stems from a baseline of frustration and inertia. Because the lack is not in ability, it’s in the structures needed for ability to transform, to progress, and in so doing, better one’s conditions, or at the least, to change them.

“Sobrang sarap sa feeling na dinadala ng Philippine flag sa mga competition na ganyan,” shares Jay-R. “Makikita mo lahat ng magagaling na surfers and mapu-push ka talaga na mag-level up.” [It’s such an incredible feeling to bring the Philippine flag to competitions like these. You get to see all the best surfers in the world, and it really pushes you to level up.]

Rather than obsess over competitive rankings, the Elyu Surf Team’s strategy has always been to focus inwardly, growing the team from the ground up. Long before they took on the world, Ian and the rest of the coaches established that attitude is just as important as aptitude, and that the attitude they needed to progress was to think as teammates, rather than competitors. “From the beginning… nasa mindset na nila yan, na kung sino mag-level up, dapat support lahat ng team.” [From the beginning this was our mindset, that the whole team would support whoever among us levels up.]

Such is the thinking behind the grassroots training program that Ian and Luke developed during the pandemic, ironically, when surfing wasn’t even possible. Unable to work or go to school, let alone surf, the La Union surf team would meet up on the beach every day, and run. Eventually, they were cycling together. Soon, neighborhood teachers like Raffy Castillo of Proper Proper Gym and movement artist Mia Cabalfin volunteered their services, and a rigorous training program developed with a mix of strength training, yoga, and even ice baths. Anyone hoping to make the national team was welcome to join, and oftentimes the gym would be packed to capacity. Ian’s goal for the program was simple: to make sure La Union was represented in the national ranking.

“Dun nag-boom yung team,” recalls Ian. “Nagkaroon ng time lahat eh. Kasi siyempre walang school. So lahat eager ng mag-surf, eager ng gumaling… may focus sa isang [bagay].” [That’s when the team really boomed, because all of a sudden everyone had time. Everyone was eager to surf, eager to progress, because we were focused on only one thing.] In a time when the world came to a standstill, the team was picking up momentum; when one of the directors of the MVP Sports Foundation came up to Elyu for the weekend, he was so impressed by their program that he donated money for equipment. Through UPSA, the coaches made sure to distribute the surfboards not just in Elyu but in various surf communities around the country.

“Kung walang pandemic, hindi naman namin sinabing hindi mabuo ng team, pero siguro mas matagal,” says Ian. [I can’t say that the team wouldn’t have come together if there hadn’t been a pandemic, but it definitely would have taken longer.] These are people who’ve known each other their whole lives; they compete, they tease, they argue, but they also help, listen, and cheer each other on. The 2023 La Union Pro last December perfectly demonstrated how surfing is, in so many ways, a family affair. In the women’s division, Daisy Valdez, one of the strongest competitors on the Philippine team, lost to her own 13-year-old daughter, Kaila, making her the youngest champion of an UPSA event. Beaming with pride, Daisy described it as “the happiest loss in [her] surfing career.”

But that wasn’t the only upset of the event. In the finals, Jay-R went up against his younger brother Jun, and lost. Jun got the highest scoring wave of the competition, and then the ocean went dead calm towards the end of their heat. “Nagusap kami ni Jay-R na parang, okay din yung nangyari,” reflects Ian. “He did his best naman na mag-champion. Sabi niya happy siya for Baby Jun, and at least makikita rin ng buong team na, world level siya, pero tinalo siya ng nasa national rank. Malaking impact yun.” [Jay-R and I talked and we realized what happened was a good thing. He did his best after all, and he was happy for Baby Jun. It was also good that the whole team saw how even an internationally ranked surfer can still lose to someone that’s only ranked nationally. That had a big impact.]

In fact, before he qualified for the world tour, Jay-R had been having a particularly bad year. “The whole year [of 2022] wala akong naipanalo na event. Lahat ng national events talo ako,” he shares. [I didn’t win a single event the whole year of 2022. I lost all my national events.] Just as when he lost to Philippine teammate Roger Casugay during the 2019 SEA Games, the disappointment only made him more determined, pushing him to train up to seven hours a day. Leading up to the tour, his coaches and teammates helped him stay focused: by committing as a team to the narrative that had brought them to this moment.

“Pumunta kami [sa US] para to represent the Philippines lang, yun lang ang goal,” shares Ian. [We went to the US to represent the Philippines, that was our only goal.] And yet, at every stop, from Huntington Beach, California, to Bells Beach, Australia, to El Sunzal, El Salvador, and finally to Malibu, California, the team had to keep revising their expectations, thanks to what was happening right in front of their eyes.

“Ang daming tinalo ni Jay-R; yung energy, tsaka yung target, nag-level up din kami.” [Jay-R beat a lot of the competition. So we had to keep leveling up our energy and our target.] The commentary from Bells Beach captures a bit of the energy that Jay-R brought to each and every heat, win or lose: “Manufacturing a score on a wave that didn’t look like it had much scoring potential, but maximizing every drop of water on this Bells wall, as he gets back up onto the nose again, and you can see that board lifting, and he grabs the rail and slides the fin and rides out, checks his watch and feels good.”

By the time Jay-R made it to the finals at Malibu, the birthplace of classic longboarding, and finished as the eighth-best longboarder in the world, the Philippine team understood. “Okay hindi lang tayo pang Philippines, pwede na tayo pang world,” says Ian. [Okay, we’re ready to take on not just the Philippines, but the entire world.]

In deconstructing Jay-R’s moment, one finds a story filled with many heroes. And so, the excellence of an individual comes to be understood in relation to the strength of the whole. When a community learns to build the support systems that its individuals need to succeed, everyone wins. It isn’t a coincidence that another surfer on the Philippine team, Marama Tokong, qualified for a different WSL world tour, the Challenger Series, soon after Jay-R did; nor that he hails from Siargao, another historic surf community that has been pivotal in the progression of the sport.

And just as his surf aunties and uncles have done for him, Jay-R is already attending to those who come after him. “Yun yung target namin sa mga kids ngayon, na parang meron sumunod sa amin. Sila naman [ipa-prop up],” he explains. [Our goal is for the kids to follow in our footsteps. It’s time to prop them up.] When Ashlee Lopez, a younger second-generation surfer, made it onto the Philippine team last year, she attributed it in part to Jay-R’s guidance. “Si Jay-R hindi lang siya coach sa amin, siya rin pinaka–kuya namin,” she shares. “Dahil sa mga challenges na pinapagawa niya sa akin during training, dapat hindi lang yung kaya ko lang gawin, dapat mas hihigitan ko lagi.” [Jay-R isn’t just a coach to us; he’s also our big brother. Because of the way he challenged me during training, I learned that I should always push myself beyond what I think I can do.]

“Ganito yung mga next generation ngayon dahil sa nakikita nila yung first generation, kung paano mag–isip, paano yung discipline,” muses Ian. “Malaking tulong yun… kasi from their parents, kuyas, and ates, na kasama sila sa foundation ng LUSC… siyempre, mahal namin ng surfing, so kailangan din naming mahalin yung entire community.” [I think the next generation is like this because from the first generation they learned how to think, how to be disciplined. It’s a big help that, through their parents and siblings, they got to be part of the foundation of LUSC… because to love surfing is to love the entire community.]

“Gusto ko ituro sa kanila lahat ng mga natututunan ko sa mga competitions,” continues Jay-R. “Gusto ko din na mas malayo ang marating nila kesa sa mararating ng career ko… Nakikita ko naman sa mga next generation na mas angat yung laro nila kaysa sa time na ganun ng age namin. Sobrang laki ng chance ng mga sumusunod na generation sa amin sa mga ganon klaseng contest.” [I want to teach them everything I’ve learned from competitions. I want them to go even farther than I will go in my own career… I can really see that the next generation has leveled up their game, especially when compared to the level of my surfing at their age. When it comes to world-class competitions, the next generation has an even better chance at succeeding.]

He hopes that this year another Filipino will qualify, so he won’t be alone on the tour. “Sa tingin ko, simula lang ’to.” [The way I see it, this is only the beginning.] Not just for him, but for all of us. While longboarding, the kind of surfing La Union is famous for, isn’t part of the 2024 Paris Olympics, it will be included in the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles.

“The Philippines is surrounded by water, it just makes sense that one day there will be a world champ from the Philippines,” says Luke, pointing out what should have been obvious, all along. “There has to be a Manny Pacquiao of surfing out there, for sure.”

“Our goal is for the kids to follow in our footsteps. It’s time to prop them up.”

The newfound sense of possibility that Jay-R brings has electrified the entire Philippine surf community, inspiring young surfers across the archipelago. Camille Pilar, writer and official anchor of the PCST calls it “the Jay-R effect.”

“Ang maganda kasi dun, sa achievement ni Jay-R,” offers Ian, “ay hindi lang para sa kanya eh, hindi lang sa para sa amin dalawa, or para sa coaches, or sa team. Kumbaga buong Pilipinas, ang laki na yung na inspire lahat na, Okay kaya ng Pilipino pala mag-compete with other countries in a world event.” [What’s great about Jay-R’s achievement is that it isn’t just for him; it isn’t just for us two, or for his coaches, or even for the team. It’s for the entire Philippines, because it’s so inspiring to know that, Okay, the Filipino is capable of competing with other countries in a world event.]

Having joined the national tour early, Jay-R took full advantage of the ramp that had been laid out by his elders, signaling to other surfers that they could, too. In fact, the Philippine team has channeled this momentum into a campaign they call the Grassroots Caravan, where they travel to different surf spots, and share their stories. “Gusto namin ikutin ng buong Pilipinas,” shares Ian. “Dinadala namin si Jay-R tsaka Roger [Casugay, the first Philippine surfing gold medalist in the SEA Games] para ma-inspire din yung ibang province.” [We want to travel around the entire Philippines, bringing Jay-R and Roger with us, so that other provinces will get inspired, too.]

“We tell them there is a future for surfing,” adds Luke. “That if you want to be a professional surfer, this is your role model, and this is how he does it: he trains hard, he doesn’t party, he doesn’t do drugs, he surfs every morning and every afternoon you’d see him train. And then the kids go, [Luke snaps his finger] ‘Okay now I know the path before me. I make sure I’m the best grassroots [surfer] in my province, so I can get the free boards, I compete in the national tour, if I finish number one or two, I’m on the national team, and if I’m on the national team, I can get enough funding to join the World Games.’”

Relatively overnight, the Philippine Surf Team has created what has been missing for decades: the shape of a future, and a way to get there. Local groms of surf spots, big and small, can now dream of a career in surfing, and work hard to actually have one.

And so, ever since an American by the name of Steve Scott first traveled from Subic to Baler to catch a couple waves in 1972, surfing has taken root across our islands. The process has been uneven, a cumulative effort of various actors and communities that happened in fits and starts, but ultimately,the sport has enacted a web of growth that’s opening up possibilities, reconfiguring social dynamics, and even, dare I say it, igniting a shaky sense of hope, even as the future remains uncertain.

Competitive surfing creates opportunities for far-flung communities, but it also opens the door to exploitation and destruction. In places like Elyu and Siargao, water, power, and pollution are worsening problems thanks to tourism, and surf competitions sometimes get caught in the middle of political feuds. Even surfing’s inclusion in the 2024 Paris Olympics is not without controversy, thanks to the ongoing construction of a massive judge’s tower in Tahiti. Despite locals reporting on the extensive damage that the tower has already done to the island’s pristine marine ecosystems, the local government has stood with the Olympic committee and pushed through with the plans.

And yet, if Philippine surfing is a story whose future is yet unwritten, it’s also a story that its various communities are telling to themselves, over and over, revising and reorganizing every step of the way, as the past shapes present, and the present opens up to an ever-changing vista of the future.

Surf communities tend to be particularly concerned with constructing a narrative that connects past, present, and future—open Instagram and you can scroll the comments of surfers squabbling over this collective narrative, featuring a worldwide spectrum ranging from boomer conspiritualist to gen-Z change-maker. This sense of lineage may seem ironic at first glance—a foolish fixation for an activity that is decidedly unfixed—but surfing is about drawing lines, after all. A wave may be ephemeral, but its journey is long, patiently gathering and organizing energy as it travels across the ocean, so that it can rise, curling across the horizon—an invitation to play; to change.

Even with individual stars like Jay-R breaking open and rewriting the game, or older, more established communities taking the lead in driving its industry, it’s a landscape that is being collectively and continuously negotiated. In a certain way, surfing can be understood as an accumulative body of knowledge, held within the individual, as much as the community, transforming people and places the same way that the ocean rewrites a coastline: over time. There’s a reason so many of the top surfers in the world come from surfing legacies, proudly multi-generational surfing families hailing from Hawaii to California, Bali to Tahiti, and now, the Philippines.

When Jay-R is coaching, he likes to tell his students to look further down a wave. That way, instead of reacting only to a narrow section of the wave, you can play with it as a whole, connecting your moves like pearls strung on a silver necklace. The more cohesive the ride, the more pleasing it is, to the surfer and her audience, both. Pleasing as in, beautiful. Pleasing, as in fun.