Stephanie Syjuco’s Inherent Vice engages with a repository of materials by Filipinos for Filipinos, in contrast to her previous work exploring American colonial records. Photos courtesy of SILVERLENS (Manila/New York)

In this interview, Vogue Philippines asks Stephanie Syjuco about the dynamics of her practice and the complexities of working with the archives.

Following the release of her monograph, Stephanie Syjuco’s solo debut in the Philippines comes at a time when discussions and reassessments on our nation’s identity and history seem to be at a crossroads. While it may be a formidable pursuit to understand the influence of the past to make sense of the present, Syjuco directs us to look into the way objects reflect cultural moments through the exhibition Inherent Vice recently held at at the Silverlens Gallery in Manila. For years, she has been mining collections and archives of American institutions to probe how photography and image-based processes come into play in the formation of history and citizenship.

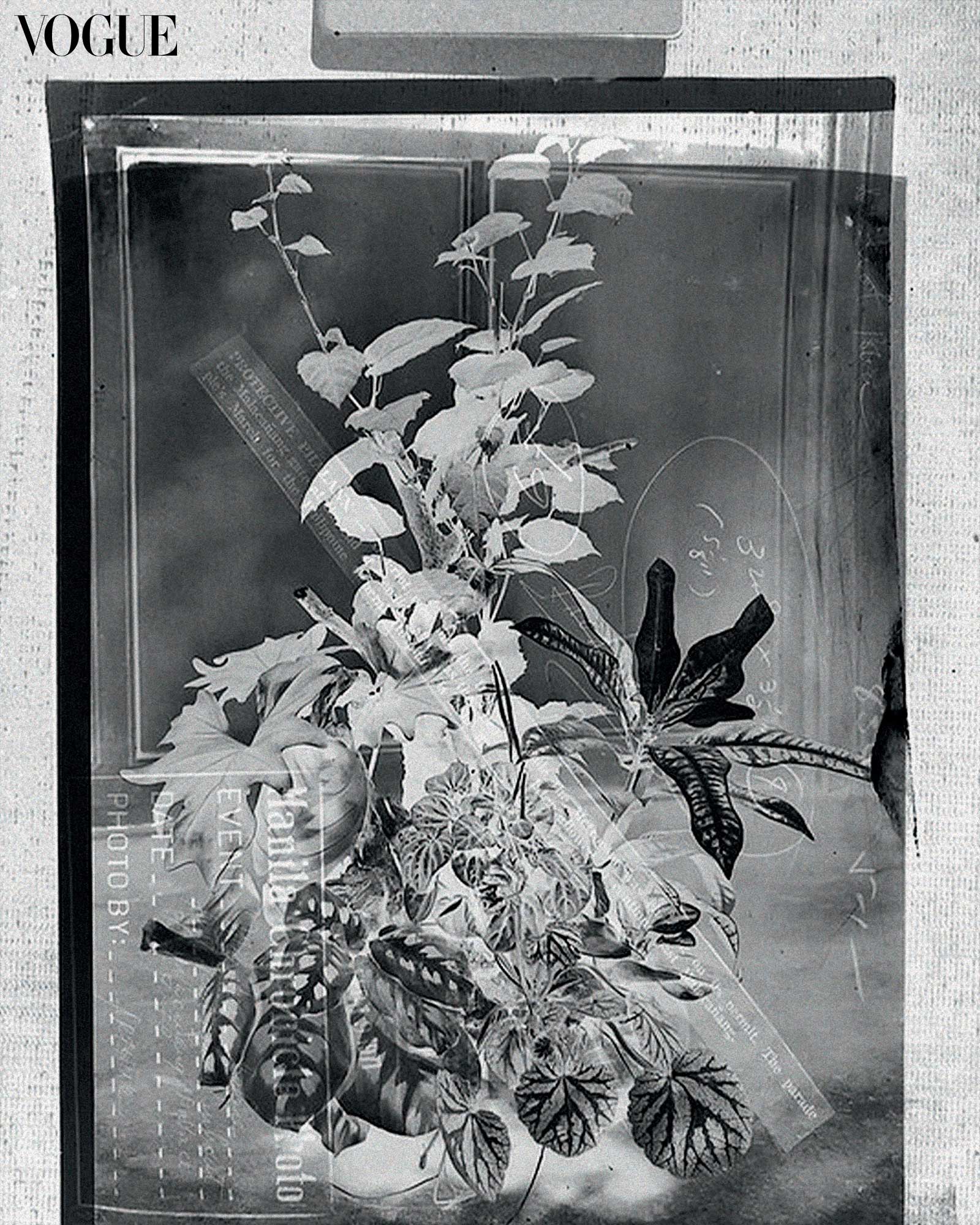

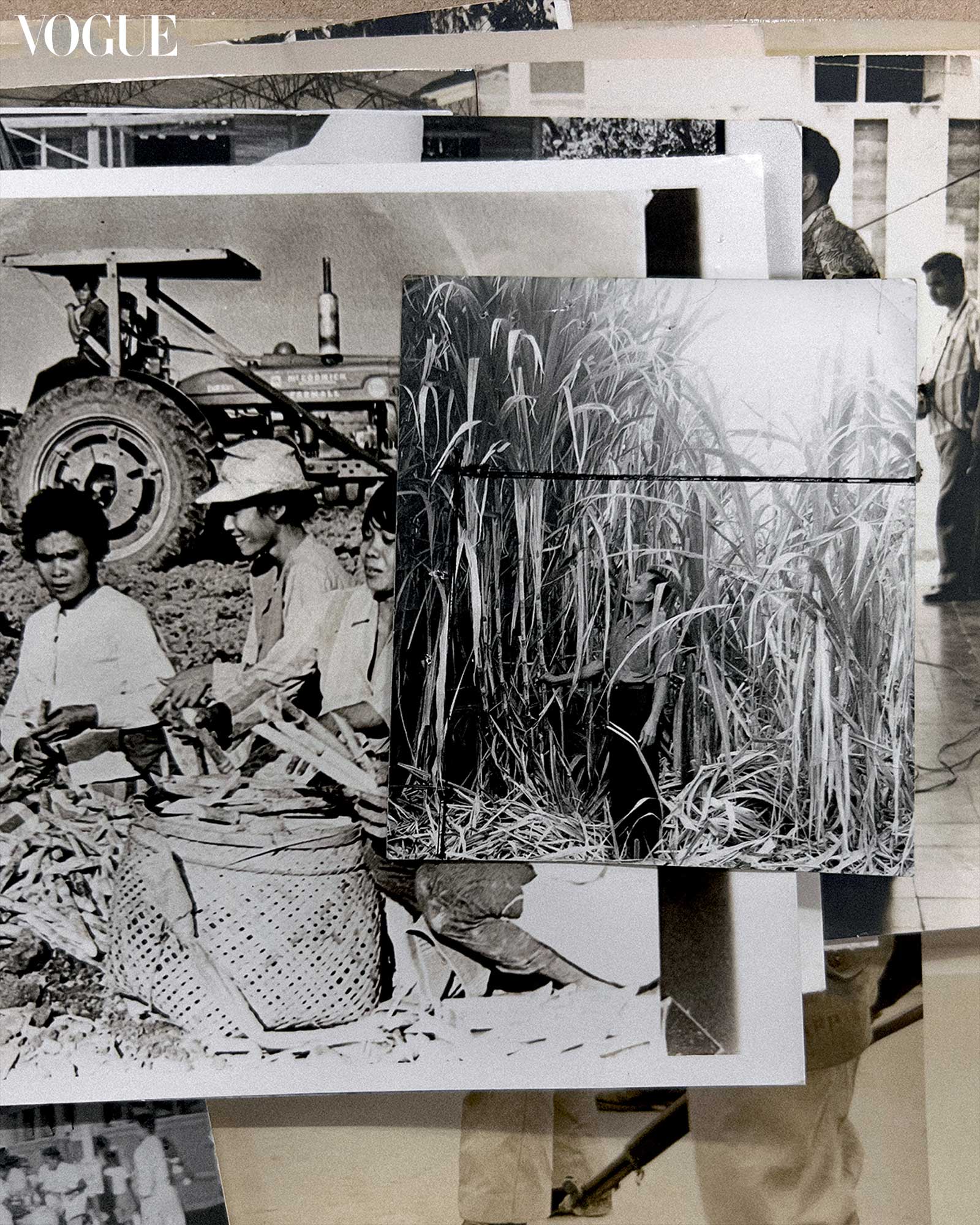

Extending this practice and working in a slightly different context, Syjuco spent weeks at the Lopez Museum and Library excavating the photomorgue of the now defunct Manila Chronicle and uncovered images that have not been seen publicly for five decades. From flowers, lavish home interiors, hairstyles, parties, sugarcane farmers, and student movements to scenes of police officers armed with rattan-made shields against protesters, these images were taken by photojournalists in the 1960s until the publication had ceased operations in 1972 with the imposition of Martial Law. Syjuco then took the task of re-photographing them as they exist in the collection and emphasizing the marks, labels, and editor’s notes in the material—an approach quite the opposite of her past works exploring colonial photographs, where she would conceal subjects of oppression as perhaps, symbolic gesture of ending colonization.

Vogue Philippines: Many people may not know that the beginning of your practice can be traced to sculpture. How does your knowledge and experience of the three-dimensional format contribute to and support your exploration of cultural objects and their contexts?

Stephanie Syjuco: Over the course of a 30-year practice as an artist, it’s only been in the last decade that I turned to photography as a method of making work. I have a tendency to think spatially, and how a viewer moves in and around artwork—I’m less interested in how a work hangs passively on a wall, so my early projects were in sculpture or installation. Plus, I love fabricating “stuff” and working with crafted, material processes. Translating that into photography has meant working very physically with images; sometimes building elaborate sets to be photographed, printing images on large sheets of papers that curl and become physically collaged onto walls, or working with immersive digitally-printed vinyl murals that absorb the viewer into the space. Maybe I’m not fully satisfied with the safety of a formal framed photograph and I like having my images push out into the physical world in some way.

In her book Potential History, the photographic scholar Ariella Aïsha Azoulay asks us to unlearn imperialism, citing the imperial governance contained in objects that can be found in many institutional archives but also discourages us from disengaging and instead challenges us to find new modes of working with them. As a practitioner who heavily engages with imperial and colonial archives, what are your thoughts on the notion of resistance by way of unlearning, and are there any methodologies from your practice that follow such?

I use the phrase “talking back to the archive” as a method of resistance in my recent monograph, “The Unruly Archive.” It sounds almost cheeky but it’s dead serious. How do those of us who find ourselves on the receiving end of a colonial narrative process images, documents, and stories told from the voice of empire? And what do we do with the problematic and often one-sided myopia of the museums and collections that embody those stories? This definitely connects with Azoulay’s critical texts about revisiting institutional sites and museum collections to examine how colonialism is an embedded legacy of their structures.

For instance, during a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship in 2019, I was able to spend an extended amount of time at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History searching for visual evidence of “the Philippines” within one of the most official US archives. What turned up was mostly US military records from the early 1900s, expedition photographs, and anthropological/ethnographic surveys in which Filipinos were the subject of racialized study but not given a voice in any way. If one were to see this as evidence of representation, one would believe that Filipinos did not exist outside of their colonial reality, which is completely untrue. By rephotographing and visually interrupting these archival images and documents, I felt I was able to short-circuit this structure and create entire bodies of artworks that resisted the gaze of empire. Making this type of work can be draining to do; the colonial American archive is intensely problematic and sifting through it can be an arduous process of seeing yourself not as how you are, but how you have been encapsulated and codified. One challenge has been how to make it a space of productive possibility and point to how the archive itself has holes and blind spots.

“I use the phrase ‘talking back to the archive’ as a method of resistance.”

In your first solo exhibition in the Philippines, you have worked with the Lopez Museum and their collection of images from the Manila Chronicle archives. How does this experience of excavating these photographs differ from working with those found in Western institutions produced with the intention of colonization? Do you begin with a concrete idea of what to look for, or at what point in the process are you able to conclude this?

Working directly with archives in the Philippines has been such a joy compared to working with US collections! In the Philippines, the colonial gaze is not the overarching structure and a fuller picture emerges of a country and its people. I mean, it sounds obvious but it’s shocking to see how completely inadequate American archives are in terms of the bigger picture.

I was invited by curator Yael Buencamino Borromeo to consider the entire collection of the Lopez Library and Museum as potential subject matter for a new project and my first instinct was to go through their colonial era holdings to see how it was reflected differently in the Philippines as opposed to in the US. But after a while I realized how much more expansive it could be if I ventured outside of the limitations of the colonial period. So when I discovered that the Lopez Museum also held the entirety of the photo archives of the Manila Chronicle, I realized that it would be much more exciting to examine how the Philippines was writing its own story in a post-colonial period via the photojournalists tasked with making images of Filipinos, by Filipinos.

Going through the Manila Chronicle photo archives (or the “photo morgue” as it’s colloquially known), was like unearthing a frozen time capsule. I focused on the period from the late 1960s to 1972, when it, like other newspapers and media outlets, were forcibly shut down due to martial law. The collection consists of thousands and thousands of black and white photos in folders arranged by subject, the vast majority of it undigitized and not available to see unless you were physically present in the archive. Many of the printed photos were never actually published, so it was like going through a vast visual collection of images that may not have been viewed outside of the photographers and editors.

I wound up creating informal arrangements of these images on the archive table and rephotographing them as dynamic juxtapositions that explored the culture and politics of pre-martial law Philippines, teetering on the edge of the shutdown. I shot hundreds of images and then had to go back to my studio in Oakland to just think about it for a while. I’ve become familiar with the process of incubation after working in an archive since I have to consider how to show these images in a way that adds to a critical dialogue and not just re-prints them. I’m deeply grateful to the Lopez team for inviting an artist to do this kind of work!

Inherent Vice is somewhat connected to your long-term probe of what it means to be a “citizen.” As someone born in the Philippines but also being an American, how does this affect your re-contextualization (perhaps) of the Manila Chronicle archives especially when many images were taken from a controversial period of our history? Are you the outsider looking in or the citizen wanting to come home?

The process of photographing in the Manila Chronicle archive was an intensely educational experience for me, and I’m incredibly proud of the work that resulted and my show at Silverlens. As someone who was born in Manila in 1974, just two years after martial law was declared, but left soon after, I have no personal memories of the time, or of the promise that existed before the crackdown. As a diasporic Filipino American, I did not live through martial law and only learned from stories or overseas reports. Holding the photographs of the political protests in my hands was an incredibly impactful experience because it created a much larger picture of what was happening, and not through the same sets of images that everyone is familiar with. What was also fascinating about this time period was that running alongside images of political conflict were images on lifestyle, fashion, and culture—because just like any national newspaper, the news of the day encompassed a multitude of subjects and not just headline events.

If I were to think of myself as an “outsider looking in” to this collection of images, it also affords me a way to learn about this time period using primary source material and not through soundbites. I had long discussions with friends and Filipinos that lived through martial law (and its effects) to find out what it meant to see these images 50 years later—were they interesting to look at? Did they dredge up complicated feelings or bring forward unspoken anxieties of contemporary conditions? What does it mean to look at these images in a new light? Can we really see these images anymore?

I’m also conscious of how my balikbayan status can result in personal blind spots when showing work in the Philippines about Filipino history. For this project, I was concerned I would be showing images that Filipinos who lived through the time would find banal or that the work would come off as pretentious. A quasi-outsider showing them things that they already knew—how boring! But I was able to spend a lot of time listening, learning, and finding space for criticality. In the end, I think I crafted an exhibition that is surprisingly fresh, given that it relies on images from an archive of a different era.

How should the Philippine audience make sense of the exhibition and do you somehow feel that there is a level of intrusion? In presenting the archives, how do we discern if we are simply making sense of history or reliving collective traumas?

The Philippines in the late ‘60s/early ‘70s was a cosmopolitan place of culture and industry as well as politics. It has a complicated history, with competing narratives and a political memory that can be quite malleable. Many younger viewers in their 20s and 30s related to me that they were really impacted by the show. When I selected images, I juxtaposed what was happening in culture as well as politics, and it’s a heady combination and sometimes a visual contradiction. Many said that they had never seen images together like that, and that it was compelling because it was so different from the abstract stories they had been told. Older visitors saw themselves in the work, and felt they could immerse themselves in memories of what they had lived through. The middle generation—my generation—had that halfway space of being in and out of it. Some viewers see the work as a critique of wealth and crony complicity as much as it is of the Marcoses and martial law, and others see it as a celebration of fashion during a tumultuous era that was also mirrored in other political struggles across the world. Some are drawn to the intense image cropping and formal aesthetics I work with, and others see it as an homage to the photojournalists of the time. I think it can be all of that and more. In addition to my images in the show, we included a display from the Lopez’ Conservation Labs, which works to preserve the archive and prevent it from deteriorating. I’m deeply invested in how caring for history and stewarding its images for future generations can also be a political act.

One of the big takeaways I have is to trust that the audience is incredibly sophisticated when viewing images, and that the nuances I intended are present, alongside images that can still pack a punch fifty years later.

- Tina Maristela Ocampo Unearths 12 Photos From Her Archive: “There’s Got To Be Fire, Enough To Burn The Studio”

- “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” Is the Costume Institute’s Spring 2025 Exhibition

- Open Stage: The Golden Gays On Song, Found Family, And Unmistakable Joy

- The Flowers, the Birds, the Beads and What Berlin-based Olfactory Artist Sissel Tolaas Wants Us To Smell At The Met’s Costume Institute Exhibit 2024