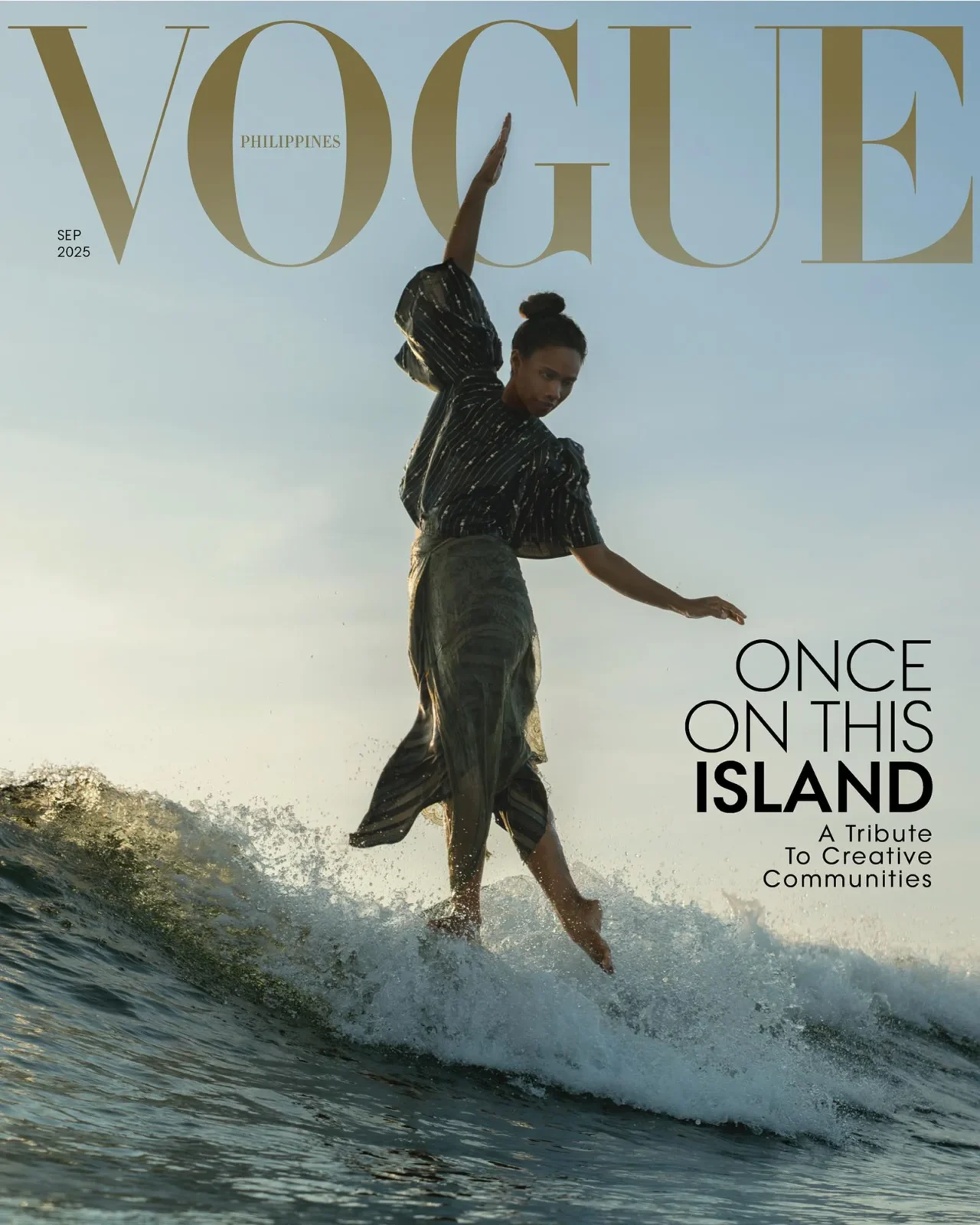

Henri Torres Calayag, Michael Salientes, Neal Oshima, and Celestina Maristela Ocampo. Photographed by Mark Nicdao for the September 2025 Issue of Vogue Philippines

From pre-digital days to the present, industry pioneers Neal Oshima, Henri Calayag, Celestina Maristela Ocampo, and Michael Salientes reflect: What does it take to create an image?

Before creative roles had titles, and before the word “editorial” made its way to the vocabulary of Philippine fashion, there were simply people who knew how to make an image sing.

From the early ’80s to the ’90s, the visual language of Philippine fashion was only beginning to take shape. At the forefront were creatives whose collaboration produced some of the era’s most unforgettable images. Among them were award-winning photographer Neal Oshima, hair and makeup artist Henri Calayag, model-muse Celestina Maristela Ocampo, and stylist and fashion editor Michael Salientes. Their contemporaries, who also helped define the time, included Jun de Leon, Wig Tysmans, and Pancho Escaler.

Of the era, one of the most pivotal images that might come to mind is from Ricky Toledo and Chito Vijandre, who in 1991 conceptualized local fashion brand Bench’s first television commercial, “A Day in a Sculler’s Life.” Set to Clair de Lune, it showed a young Richard Gomez gliding across the sparkling waters of the Pasig River, oars cutting through the light, dressed in a white tank top with “Bench” emblazoned across the chest. The TVC won Best in Cinematography at the 12th Advertising Congress Araw Awards in 1990, marking an era when Philippine advertising was also at its most ambitious.

At the time, image-making was an intimate art. The only people on set were the photographer, the model, the hair and makeup artist (usually pooled into one), and the stylist. A collaborative chemistry was key. Before the onset of glossy magazines, fashion spreads were printed onto newsprint magazines and newspapers that would yellow over time. Images were shot on Polaroids and then film, which meant there was little room for error, and no digital safety net. “You had to have full trust and intimacy with each other,” Calayag remarks.

With so few people on set, shoots often ran on instinct and synergy, as compared to pre-production decks or fixed shot lists. “That was our training ground,” Calayag continues. “We don’t plan [anything.] Whatever comes to your mind, whatever your vision, you have to be really good as a visionaire. Kailangan ang energy niyo pantay-pantay kasi magjijive kayo dapat eh. [Your energies need to match, because you need to be in sync.]”

In a budding industry where resources were limited, creativity became the only currency, making space for a boundless world of imagination. At the time, Philippine fashion existed on two extremes: mass-market retail or made-to-measure designer wear, with very little in between. Styling a shoot meant building a story out of what was available.

When Michael Salientes returned to Manila in the early ’90s after years in New York, he brought with him a clearer understanding of what editorial styling could be. But the role of a stylist was still unfamiliar. “Every single person I met, I was always asked if I did hair and makeup,” he recalled. As the country’s first formal stylist and fashion editor, Salientes says he had to introduce the concept of editorial work from the ground up. “I had to explain that I was selecting clothes, pulling out, so that their clothes would be featured in a magazine, and that I was trying to tell a story. I had to explain that an editorial is the magazine’s point of view. It’s the magazine’s way of telling a story, [and displaying] what’s new, what’s in, what’s fresh. It took a few years until they caught on.”

Beauty tools were just as limited as clothing. With only a small selection of brands available, Calayag learned to work with less, and make it look like more. It wasn’t until later, when global beauty brands began entering the local market, that there were wider options. But in those early days, he says, there was a certain magic that came with improvisation and spontaneity.

Everything Calayag knew about creative direction and beauty was rooted in personal experience and sharpened through years of performance. His storytelling instincts came from his time on stage as one of the Paper Dolls, a group that pioneered drag in Manila in the 1970s. On set or on the runway, he conceptualized characters. Finding a muse in Ocampo, who he says was their “blank canvas,” he often gave her a storyline to embody, turning each look into a scene.

Ocampo came into fashion through a Ben Farrales show, and from there, her calendar quickly filled with bookings. On the runway, her elegance and ease were likened to French supermodel Inès de la Fressange. She became a favorite for finales and covers alike, not just for her beauty but also for her presence. Her contemporaries say her body would tell the story as much as the garments did, and her ability to transform on command made her indispensable to every image she helped bring to life.

This was the age of Anna Bayle, when models were recognized for their signature walk, every strut a performance. In one Inno Sotto gala show, Calayag recalls assigning Ocampo the role of the weeping bride. And cry she did, walking down the runway in full bridal wear and in character. In another shoot, Ocampo was prompted to embody American actress Joan Crawford, and Calayag stuffed cotton inside her jaw to mimic the actress’s sharp bone structure. This improvisation, he said, was their speciality. They were quick and sharp.

“It was always an interesting process, shooting. We were just having fun. And I loved that, I miss that actually. It was really playtime for us.”

Advertisement

Looking back, Ocampo reflects on their synergy after their Vogue Philippines shoot, which marked the first time they were all photographed together: “Henri isn’t just our beauty transformer; he is the heart and soul behind every image Neal created every time the three of us worked together. I consider myself incredibly lucky to have been the subject of their choice to bring their art to life.”

Questioned about what constitutes a good image, their answers came without pause: a great photographer, one who understands the language of instinct. In their years working with Oshima, for example, they recalled shoots that often evolved midstream. “We always started with something, but sometimes we’d end up with something completely different,” shares Salientes. “It was always an interesting process, shooting. We were just having fun. And I loved that, I miss that actually. It was really playtime for us.”

At the core of their craft was this sense of play and an insatiable desire to create. In fact, in creating some of the most unforgettable images in Philippine fashion history, these catalysts were neither chasing fame nor fortune, or even legacy. “It was so simple,” Calayag shrugs. “When I wake up, I just have to create.”

“Up to now, I still have joy doing it,” he continues. “I’m so happy that we’re bridging this to the new generation, and that they’re also learning from our history. This is their time to be the new historians.”

What once took a handful of visionaries now takes a village. Stepping into the Vogue Philippines shoot, the pioneers took notice of how different it felt: more people, more roles, more hands working toward one image. There were editors, writers, assistants, production teams all at the ready behind the lens. From a small group of artists to an entire ecosystem of creatives, it’s apparent that the evolution of Philippine image-making is no accident. It’s the result of groundwork laid by those who came before, and dared to dream it into being.

By BIANCA CUSTODIO. Photographed by MARK NICDAO. Creative direction by NEAL OSHIMA. Talents: Henri Torres Calayag, Michael Salientes, Neal Oshima, and Celestina Maristela Ocampo. Styling: Renée de Guzman. Makeup: Gery Peñaso using Dior Beauty. Hair: Misty Gabriel. Deputy Editor: Pam Quiñones. Fashion Editor: David Milan. Beauty Editor: Joyce Oreña. Media Channels Editor: Anz Hizon. Art Director: Jann Pascua. Fashion Associate and Stylist: Neil de Guzman. Producer: Julian Rodriguez. Vogue Man Writer: Gabriel Yap. Media Channels Producer: Angelo Tantuico. Multimedia Artist: Mcaine Carlos. Senior Lighting Technician: Villie James Bautista. Assistant Photographers: Arsan Sulser Hofileña and Crisaldo Soco. Photo File Manager: John Philip Nicdao.

- Over 200 Filipino Creatives, Spread Across Decades of Behind-the-Scenes Work, Unite to Share the Frame

- How Filipino Creatives in Berlin Are Shaping Its Contemporary Scene

- How These Filipino-Australian Creatives Found Their Own Spaces to Thrive in a Global Landscape

- The Mahal Kita Crue Is Building a Home for Filipino Creativity in Copenhagen