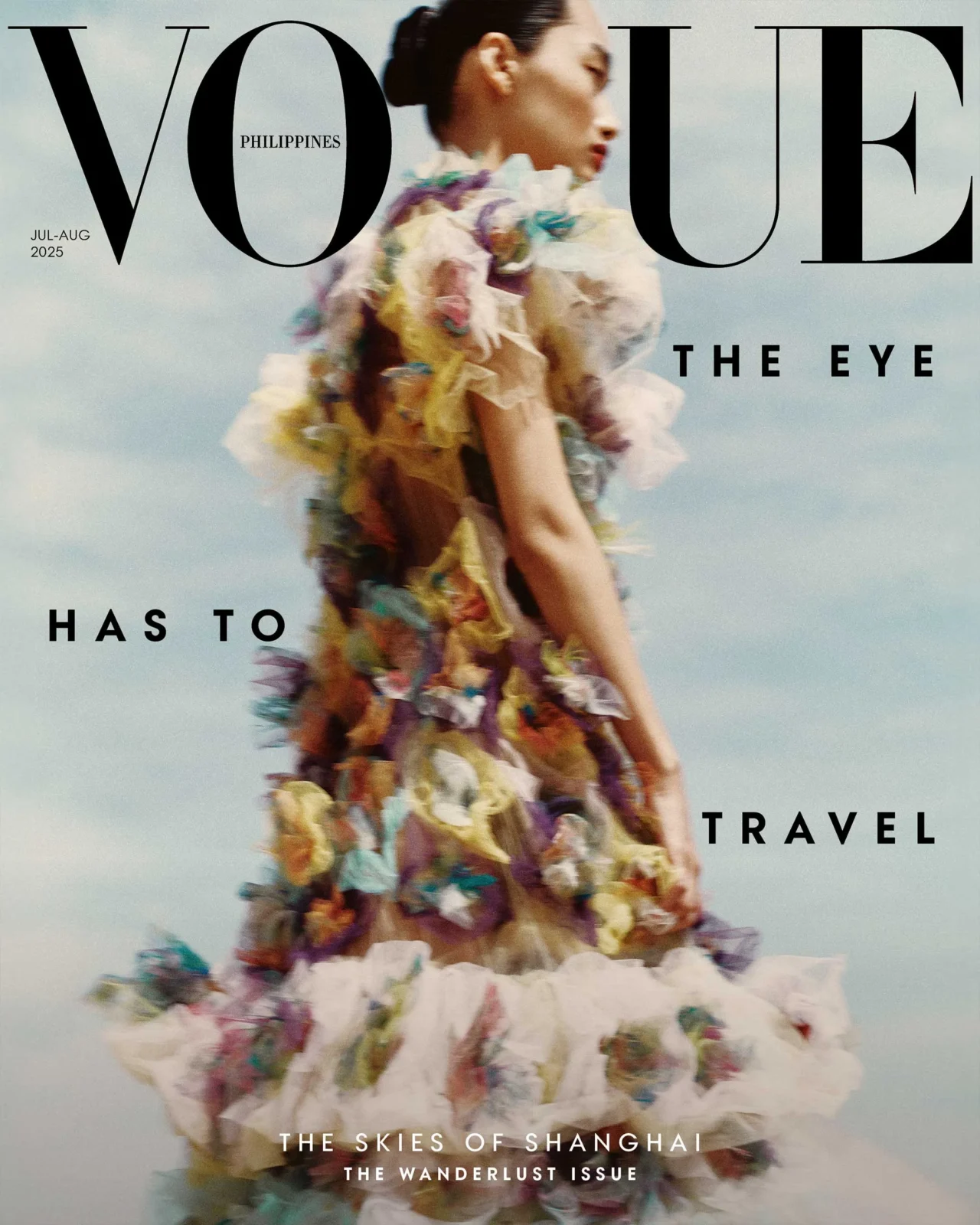

Dr. Patrick Flores with Zóbel’s “La Vista XXVI (The View XXVI),” 1974 from the Colección Fundación Juan March, Museu Fundación Juan March, Palma. Photographed by Zantz Han for the July/August 2025 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Dr. Patrick Flores with Zóbel’s “La Vista XXVI (The View XXVI),” 1974 from the Colección Fundación Juan March, Museu Fundación Juan March, Palma. Photographed by Zantz Han for the July/August 2025 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Curator Dr. Patrick Flores bridges worlds with Singapore’s first solo exhibition on Fernando Zóbel.

When Fernando Zóbel, the artist, suffered a stroke in 1980, one of the first things he asked for in the hospital was paper and a pen. He quickly sketched something, wanting to make sure he could still draw. This little-known story was shared by Zóbel’s nephew, Alejandro Zóbel Padilla, at the opening of the exhibition Fernando Zóbel: Order is Essential, the most comprehensive survey of the artist’s work to date, on view at the National Gallery Singapore. Zóbel would live for four more years, practicing his art until his death in 1984 at the age of 60.

The exhibit builds upon Zóbel: The Future of the Past, which opened at Museo Nacional del Prado in 2022 in Spain, followed by a restaging at the Ayala Museum in the Philippines in 2024, the two countries he called home. Order is Essential is also designed for new audiences, situated in the Southeast Asian hub of Singapore, where the NGS is a focal point of global modernism. Highlighting Zóbel’s many roles as artist, collector, scholar, and museum creator, the exhibit reflects on the Western and Eastern influences in his work that informed his erudite cosmopolitanism.

Putting together this expansive exhibit are two Filipinos at the NGS: chief curator Dr. Patrick Flores and Clarissa Chikiamco, along with Manuel Fontán del Junco of Fundación Juan March in Madrid, and Spanish art historian Felipe Pereda. Flores, who has been serving as the deputy director of curatorial and research at the NGS, was appointed chief curator late last year. We were fortunate to have Flores and Chikiamco tour us around the exhibit prior to its public opening; as someone who had only a glancing knowledge of the artist and his place in the Zóbel de Ayala multiverse, I appreciated their insight into Zóbel’s rigorous thinking and disciplined approach to art, his generous spirit, and his contribution to Philippine modernism.

Structured into five thematic sections, the exhibition highlights Zóbel’s artistic journey across continents and his encounters with various movements. “Half of this haunted monk’s life” begins with his first and last recorded paintings: a copy of a Van Gogh from 1946, and an unfinished painting evoking a bridge from 1984. Paired together, this prologue frames his lifelong dialogue with the past and the future and offers a poetic initiation to the exhibition. “Zóbel was a bridge between cultures, between artists, also between geographies, and between modernisms,” Flores explains.

The next section, “With every single refinement,” explores Zóbel’s early years as a student artist at Harvard and RISD, where he was exposed to diverse, experimental environments that laid the foundation for his distinct approach to abstraction. He was especially impacted by Mark Rothko’s paintings, which convinced him to abandon representation altogether.

Returning to Manila, the section “Thin lines against a field of color” shows how Zóbel incorporated local motifs and found his own technique in modernist experimentation. Wrestling with the problem of how to create thin, controlled lines of paint, he observed a chef writing “Happy birthday” in icing on a cake, which gave him the solution: to use a syringe. This led to the creation of his Saeta series, paintings whose scaffolding of lines were likely informed by the construction scenes he witnessed at work (he was also employed at the family company). The Saetas, which means arrow or dart in Spanish, became one of Zóbel’s defining series, comprising nearly 100 paintings created in the span of two years. Amazingly, photos of his artist’s studio shows an immaculate white space free of clutter or paint splatter. “Order is essential,” he has said. “In the widest sense of the word, order is one of the secrets of what I recognize as beauty.”

In 1960, Zóbel decided to become a full-time artist, leaving the family business and his other job as a much-loved professor of art appreciation. Before departing, however, he donated to Ateneo his collection of paintings from his contemporaries in Philippine modernism, from H.R. Ocampo to Lee Aguinaldo and Jose Joya. This endowment formed the collection of the Ateneo Art Gallery, the first museum of Philippine modern art.

The section “Movement that begins its own contradiction” focuses on his years in Madrid, where he began his Serie Negra paintings. “Zóbel began to feel that color was actually a distraction in his work, and Zóbel is all about eliminating distractions,” says Chikiamco. “So he decided to pare it down to just black and white. But he was also wondering how he could still produce that sense of vibration, that sense of movement.” Zóbel achieved this by wiping the edges of his brushstrokes, creating the motion blur of flight, as in the case of his Icaro paintings.

The final act, “The light of the painting,” is about Zóbel’s later years in Cuenca, where he established the Museum of Abstract Spanish Art inside a row of medieval houses perched on a cliff. As he did in the Philippines, Zóbel had generated a collection of art from his Spanish peers during a time when no institutions were doing so, a radical act that provided public context for the contemporary art of two countries, as Fontán del Junco explicates in an essay. Zóbel bought paintings from his friends not just to support the scenes but to create a record of them, movements to which he also belonged.

The exhibit also presents Zóbel’s work alongside that of his contemporaries from Philippines and Spain, as well as Chinese and Japanese calligraphy and European medieval imagery, artforms he consistently engaged with and reinterpreted. Flores says that by contextualizing Zóbel’s practice within Southeast Asian and global art histories, Order is Essential affirms the Gallery’s commitment to shaping new perspectives on art and deepening cross-cultural dialogue.

With a background in art history and regional curatorial practice, Flores’ new role as chief curator of NGS puts him in a position to bridge scholarly research and public engagement, overseeing the museum’s exhibitions combined with its education and public programming. Order is Essential goes in depth into the intellectual thought behind Zóbel’s work, but it has something for everyone, including a flamenco performance inspired by the saeta (which is also a mournful flamenco song), drawing activities for children, and reading tables for art specialists.

“The museum serves a general audience, although the material is quite specialized. There is always this tension between the popular and the specialized,” Flores says. “You don’t dilute the complexity, but maybe you stage it differently.”

In the 1990s, Flores emerged as a key interlocutor for Philippine art at a time when a regional cultural identity was beginning to crystallize. With an MA in art history, he was writing critically about Philippine art when “there was a demand for representation of what was happening in the country, in the context of the region,” he says. “Then the curatorial tasks came naturally, because they wanted some kind of representation, not only in discourse, but also in exhibition making.”

His participation in curatorial teams for major platforms like the Asia-Pacific Triennial and Under Construction, organized by the Japan Foundation, were turning points in his career. “It took me farther away from just art historical work, because curatorial work involves more moving parts.” These roles require going beyond academic research to dealing with artists, institutions, and the public. He has chaired the Art Studies department at UP, served as curator for the Jorge B. Vargas Museum, and in 2015 he curated the Philippines’ memorable comeback pavilion at the Venice Biennale, reestablishing the country’s presence on the global art stage. “Our collaboration [for the Biennale], was a testament to his facility to deftly weave thought provoking narratives,” says Sen. Loren Legarda. “I am confident that in his new role at the National Gallery of Singapore he will continue to challenge conventional perspectives, foster meaningful discourse across borders, and inspire new generations of art experts.”

At NGS, Flores’ mission is threefold: to expand understanding of Southeast Asian art by filling the gaps in research, such as the role of women and diasporic artists, and rethinking the dominant methodology of privileging art history as the main lens for interpretation. The second is to question conventional regional boundaries. Rather than being limited to constructions like ASEAN, he proposes alternative mappings around Austronesia, the Indian Ocean, or Pacific Island networks. “It takes us elsewhere and makes us belong to another world, another geography, another ecology,” Flores explains. “We get a different way of defining ourselves or the things we express.”

The third is bringing together curating and learning, which we see in how the programming around the Zóbel show seeks to engage audiences on different levels. By positioning Zóbel as a transcontinental artist who shaped modernism on both sides of the hemisphere, the exhibit embodies the vision of how a people’s museum can reframe narratives, broaden cross-cultural understanding, and make art accessible to all.

Fernando Zóbel: Order is Essential will be on view at the National Gallery Singapore until November 30, 2025.

By AUDREY CARPIO. Portrait by ZANTZ HAN. Photos courtesy of National Gallery Singapore.