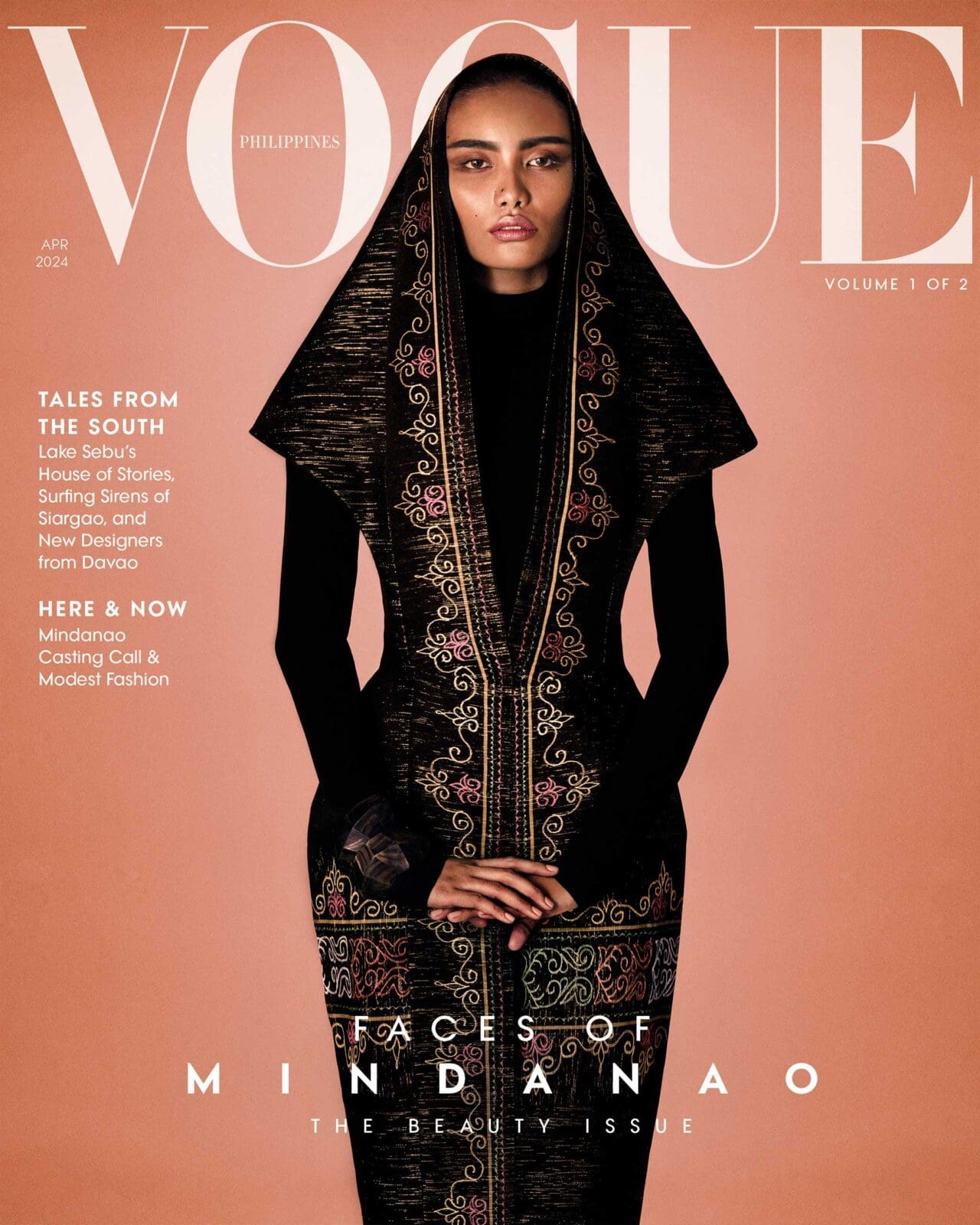

Photographed by Artu Nepomuceno for the April 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines.

Evelinda Otong-Hamja, a Yakan weaver and

entrepreneur, champions their community’s crafts. Photographed by Artu Nepomuceno for the April 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines.

In Zamboanga, the YAKAN VILLAGE is home to people and weaves with colorful stories to tell.

Without a tour guide or local friend, it’s easy to miss one of Zamboanga’s most culturally-charged corners. Type in the address on Google Maps and you’ll get a location pin, but click on Street View and you won’t find an entrance. The directions will lead you to a busy road in Barangay Upper Calarian, where the destination is tucked next to an aqua green building. The only indication of its existence to an unknowing outsider is a meter-long tarpaulin that reads, “Yakan Village Weaving Center.”

Stepping through the archway, the compound is deeper than it looks. To the right are about ten merchants, while to the left is a set of steps that leads to more shops. Each booth is dense with a melange of geometric colors: polo shirts, bags, coin purses, pouches, accessories, table runners, and placemats, all crafted from Yakan weaves.

“Yakan refers to the majority Muslim group in Basilan, an island province just south of Zamboanga peninsula,” writes award-winning writer Rosalie S. Matilac in her 1994 article titled “Yakan.” She continues, “‘Basilan’ may mean ‘the waterway into the sea’ or may derive from the Yakan word for ‘the way to the iron’ because of the presence of minerals in the island.”

Formed in 1974, the village houses over 300 Yakan families including that of Serge Ilul, their tribal leader. He recalls the day a number of them journeyed from Basilan to Zamboanga when he was just in his mid-teens. “It was way back in the early seventies when there was a skirmish between the Moro National Liberation Front and the military, so we were forced to leave the place empty-handed. [Then] we stayed here, around fifty Yakans, scattered all over Zamboanga city in different churches and good samaritans that housed us.”

After a year, Ilul says they grew bored because they “were not used to relying on relief goods.” Together, the community searched for a place where they could find work and grow vegetables. Gesturing around, Ilul shares that the property was owned by the Christian and Missionary Alliance Churches of the Philippines (CAMACOP), who welcomed them to cultivate it. In the 80s, when CAMACOP decided to put the nearly two-hectare property up for sale, the Yakan were prioritized. They ended up purchasing it, and what used to be a mountainous piece of land with no residents became their home. “We planted cassava, we planted corn, all these staple foods. Some cut timbers just to meet the needs. And then the weaving was revived when we stayed here. My mother is a weaver.”

According to Matilac, Yakan textiles were exported to various parts of Southeast Asia as early as the 9th century. She explains, “Tennun (weaving) is an artistic ability that is a source of pride for Yakan women who are famous for their beautifully woven traditional costumes of cotton and pineapple cloth. When a girl is born, the panday cuts the newborn’s umbilical cord with a bayre, a wooden part of the loom used for beating the weft. This practice ensures that the female infant will grow up an expert weaver.”

The practice is no longer prevalent, but the Yakan continue to preserve and pass on the craft in their own ways. One example would be fourth generation Yakan weaver Evelinda Otong-Hamja, whose shop is just across Ilul’s. Like their tribal leader, Evelinda traveled to Zamboanga from Basilan, but in her case, she moved after high school with the goal of attending college. Holding out a plastic-covered Mabuhay magazine, she reveals that it was her 17-year-old self on the cover, when she was interviewed and photographed for a story on Philippine indigenous groups.

She eventually became a medical technician in Saudi Arabia, but moved back home to be closer to her family and realize her long-time dream of becoming an entrepreneur.

It was 2018 when she put up Tuwas Yakan Weavers, a collective of about thirty to forty Yakan weavers who are all cousins. Most are based in Basilan while a few others, like Evelinda, reside up the steps of the Zamboanga village, behind the shops.

She formed the group when she observed that designers and artists had no way of directly working with the community. “Gumawa ako ng [Facebook] page. Nag-introduce kami na we are still here, may mga Yakan pa na legit na puwede niyong kontakin. Yun ang purpose ko, para makilala kami. [I made a Facebook page for us. We introduced ourselves, saying, we are still here, there are still legit Yakan weavers that you can contact. That was my purpose, so people would know who we are.]”

In their community, girls are taught to weave as young as age seven, and they start with five-inch coasters. They’re gradually entrusted with larger and more complex projects as they age, like the saputangan, a square cloth worn on the head. The same term is used for one of their most difficult weaves which follows no pattern; it is drawn straight from the weaver’s mind and is usually “nature-inspired, from crab, fish, bamboo,” enumerates Ilul. “It’s memory, counting; you must be clever [about] what would be the next [sequence in the pattern].”

Like Evelinda hoped, Tuwas has exposed Yakan weaves to a wider range of audiences. In her shop, a bunch of exhibitor IDs are hung on a shelf’s corners like medals—a proud display of where Tuwas has taken their weaves: Manila FAME, HABI, CulturAid, Likha, the Philippine Textile Congress, and even events in London and Brunei. Evelinda is grateful to these artisanal markets and events for giving Yakan weaves a platform, and also pays gratitude to the DOST-PTRI (Philippine Textile Research Institute), who is “paving the way to weaving in natural fibers.”

She no longer weaves as often as she used to, because her days are occupied with managing Tuwas or taking care of her kids. Her seven year old daughter has started weaving. The more they weave, Ilul says, the more people are drawn to the Yakan’s striking patterns and hues. Because of the support for their crafts, it has become a source of livelihood and provision. He beams when he shares that for the younger Yakan, “some graduated just because of weaving.”

Over time, Ilul has come to realize that the Yakan weaves are invaluable. In a room behind his shop, he keeps a small collection of textiles as old as seventy to a hundred years old. Taking one out of a sealed plastic bag, he says, “this was woven by my lola [grandmother], the mother of the Gamaba Awardee Ambalang [Ausalin]. She weaved it for me in the early 70s.”

Of an even older weave, he says he was contemplating on selling it for 25,000 pesos before finally deciding to keep it. “It’s a rare piece,” he explains with a smile. “Where can I get that again?”

-

Capturing A Modern Mindanao: Behind The Lens of Neal Oshima and Mark Nicdao

- Meet Shaira Ventura, Vogue Philippines’ April Cover Model of Muslim and Tausug Roots

- Here, Now: Vogue Philippines Shares The Stories of The Fresh Faces of Mindanao

- South Bound: The Reinvention of Indigenous Textiles By Niñofranco Creative Director Wilson Limon