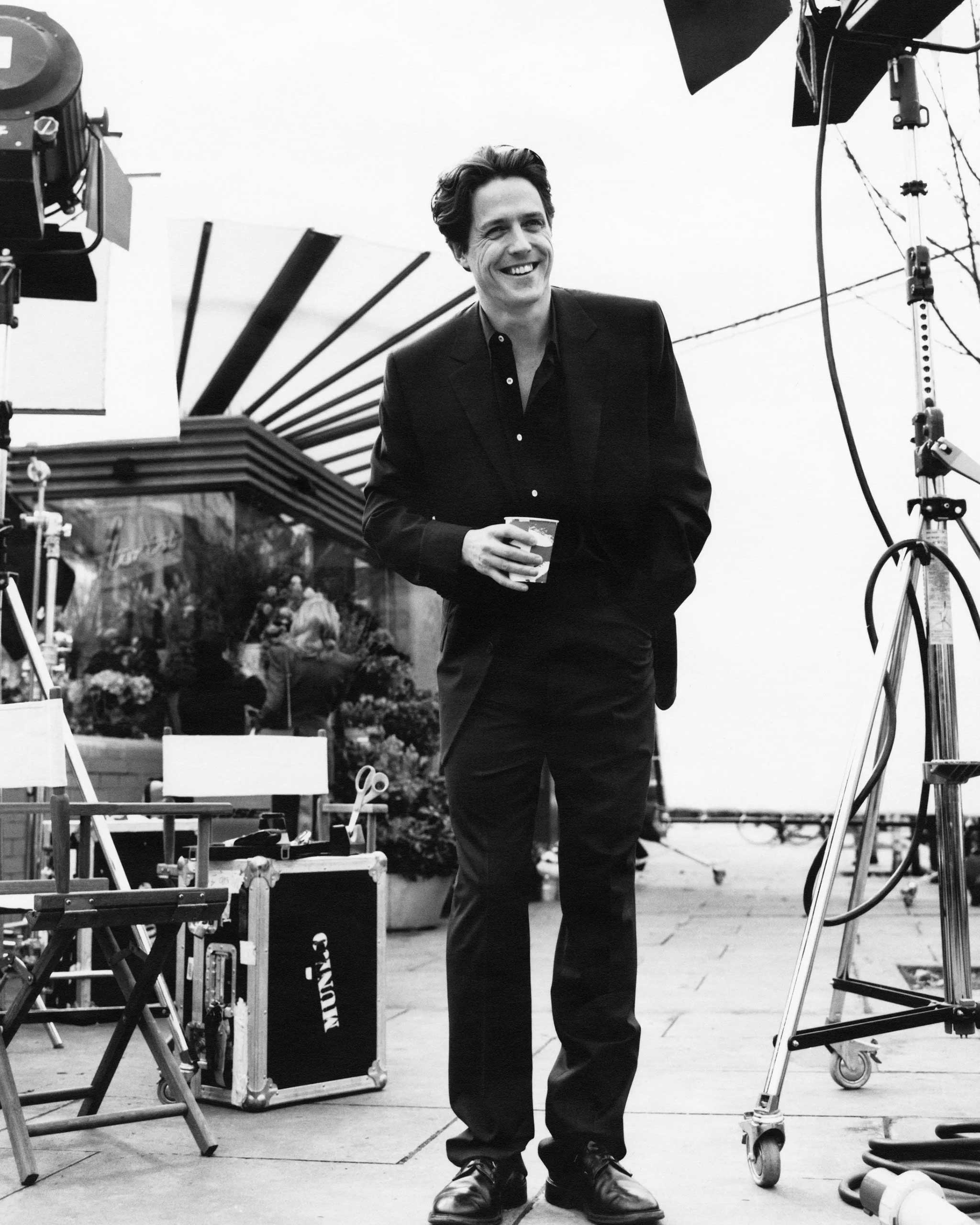

Tom Munro

For British Vogue’s February 2024 cover story, Richard Curtis interviews Julia Roberts about her dazzling, Oscar-winning career and the rom-coms that launched it, including Notting Hill. When the film premiered in 1999, however, the magazine ran an interview with its leading man rather than Roberts. “In his films he’s a foppish, floppy-haired, perennially tongue-tied upper-class Englishman,” reads the story’s intriguing introduction, “but off-screen Hugh Grant is an altogether more complex character: intelligent, witty, neurotic. Perhaps even a little dangerous.” Read the full interview, first published in the June 1999 issue, below.

It’s a gloomy London Sunday evening and I’m standing on an empty street in South Kensington feeling like the rest of the world has gone away for the weekend, when a big black Mercedes pulls up beside me. The electric window rolls down, and a man’s head emerges. “Hello?” he says inquiringly. I know that the man is Hugh Grant, because we have arranged to meet outside his office, but something doesn’t seem quite right. Maybe it’s just the way he’s parking the car – not in the first available space, but further up the street, as if he fears being followed, or maybe it’s the way he’s walking back towards me, almost limping, with one hand on his back as if in pain. Whatever, this man in a stern black Hackett coat doesn’t look like the bouncy, bright-eyed Hugh Grant that I have seen bounding about on screen, but I follow him anyway as he unlocks the front door and edges upstairs to the suite occupied by Simian Films, the production company that Grant runs with his partner, Elizabeth Hurley.

“Tea?” he asks, sniffing an open bottle of milk with faint distaste.

He makes two cups, looking as if he would prefer not to, and we sit down – him perched ramrod stiff behind a desk, guarded by a computer, and me on the other side, safely at arm’s length. On the walls around us are pictures of a more recognisable Hugh Grant, gazing down from the film posters that chart his career: the sweetly funny, floppy, fresh-faced poppet who radiates a certain kind of aristocratic charm in Maurice, Privileged, Sirens, Bitter Moon, Sense And Sensibility, Four Weddings And A Funeral, and now Notting Hill. The man in front of me has the same smooth, unblemished skin as the boy in the pictures, the same extravagant quantities of hair, and the same wondrously clear blue eyes. But like I said, there’s something different: not just in the walk, but in the talk, which is sharper and somehow more dangerous than I had imagined.

Perhaps I should have been prepared for this. Elizabeth Hurley had told me on the telephone several days before that “he is way brighter than the characters he plays. And of course he’s neurotic – neurotic and clever, without any doubt.” She’s also warned me to avoid the subject of Divine Brown, the Los Angeles sex worker that Hugh Grant had picked up on the street five years ago (“If you mention that, he’ll be very, very angry”). The tabloid tornado that followed in the wake of his arrest, sucking Grant and Hurley into its grey heart, doubtless contributed to Hugh’s subsequent refusal to talk to the British press, which is probably why, after all those years of grim silence, he is now looking so nervy.

Still, he gathers himself together, grasping his cup of tea as if it were a weapon and planting his polished black brogues firmly on the floor, and we begin at the beginning, further back even than his decidedly un-aristocratic childhood in suburban west London. “Dad is an ex-army officer who went into the carpet business not because he liked it, but because it was a way of feeding his family. The army wasn’t really his cup of tea, but his family had been in the same regiment for generations – the Seaforth Highlanders, a very cool bunch, actually.” You can see in his phrasing why Hugh Grant has so often been cast as the attractive yet comically hesitant upper-class Englishman, a role he might feel marooned in, at 38 years old, now that a post-Trainspotting generation of younger British actors is hurtling through Hollywood.

But the story in which Grant has chosen to kick off this interview casts him in a slightly different light. “I really want to make a film about the regiment,” he says, loosening his cufflinks and pushing up the sleeves of his crisp blue shirt as he settles back into his chair with more ease than before. “There’s one great episode, involving my grandfather and what he got up to in the Second World War. When I tell this story in Hollywood, agents and film executives sit bolt upright, eyes wide open, instead of looking glazed.”

His story, he continues, is about honour. “The Seaforth Highlanders had this tradition where you fought to the death, you didn’t surrender. Then, in the Second World War, after Dunkirk, the Highland division was cut off and surrounded by terrifyingly superior German forces. My grandfather, who was a relatively junior officer at the time, ended up in command of the entire Highland division because everyone else was getting killed. And he had this horrible decision to make about whether to surrender or not, because they were being mown down in their hundreds of thousands. He said, well, we must fight on, and the slaughter went on. In the end he did surrender, but he was haunted by it for the rest of his life. He woke up every night of his life in a state of panic because he had done the wrong thing and let the side down.”

Hugh Grant, one would guess, knows something about the torment of letting the side down. (“Last night I did something completely insane,” he said on the morning after his arrest with Divine Brown. “I hurt people I love and embarrassed people I work with. For both things I’m more sorry than I can possibly say…”) But there may be something else that he identifies with in his grandfather. “He was also obsessed with escaping – he was one of those nutcase escapers who spent his time tunnelling out of POW camps. His hands were all curled up when I knew him, from tunnelling…”

Hugh’s own hands are as smooth as his porcelain face, as befits a pretty boy who grew up to be a film star rather than an army officer. Indeed, he tells me, via email, a few days after our meeting, “I suppose it did cross my mind when I was young to join the Seaforths, but to be frank I’ve never really been able to bring off the whole Scottish thing. Kilts make some men look manlier. They make me look like I’m wearing my mother’s Peter Jones skirt. I think I was about 11 when my grandfather died. As I recall, he never really thought I’d make a soldier and had me down as a diplomat (oiliness, deceit). My grandmother, on the other hand, was utterly convinced I’d wind up as the Archbishop of Canterbury and, to be honest with you, I’ve never entirely ruled it out.”

Perhaps his own dreams of escape are evident in that camply witty, well-turned line of online prose. Grant talks often of wanting to give up acting, and when I tell him that his Oxford contemporaries say they always thought he would be a writer, he says, “That is still my fantasy. I should do that. Maybe as soon as these films are out… But I don’t know, I’ve probably wasted so much time now. But a couple of hours spent at the word processor makes me feel like a completely different girl…”

“I suppose it makes you feel more in control,” I say.

“Yes, yes!” he says, his usual amused drawl giving way to something more animated. “What I can’t bear about acting, is the older I get, the more frightened I get. You can be frustratingly good in rehearsal, and then when the camera turns over, you’re never quite as free and easy. That’s very, very annoying, and that frustration accumulates, and it drives me potty. But if you’re writing, well, you don’t get nervous in front of a word processor.”

When Simian Films’ second film, Mickey Blue Eyes, is released later this year, there will be further opportunity to judge Grant’s writing talents, for, although he is not credited as its author, he confesses to having written most of the script, in which he stars as – yes – an upper-class Englishman who falls in love with a New York mobster’s daughter. The first film produced by Grant and Hurley, Extreme Measures, was not a success (“That was an insane thing to do,” he says, “something with no jokes, about the physically handicapped and the homeless – it’s not what you would call box office gold”), but he has higher hopes of Mickey Blue Eyes. “It’s had these phenomenal test screenings.”

He says that he “will never have two better parts for myself than Notting Hill and Mickey Blue Eyes – NEVER!”, yet also admits to sometimes feeling typecast.

I ask if he ever worries that he is turning into a cliché because of his immutably boyish appearance.

“Well, you know I did try to change a few years ago,” he says, tugging at his long fringe, “when I had all my hair cut off by Elizabeth’s brilliant hair person, you know, Serge Normant. He said, ‘Yes, I can do it, it will be sexy!’ I thought it would be butch. But unfortunately I looked like a butch lesbian, so I had to grow it out. Disaster, actually. But I might try again. I’m dying to have short hair. I do feel like a complete anachronism. But the problem is, I’m pug ugly with all my hair cut off. Elizabeth couldn’t even look at me, could barely talk to me.”

So is it true that your company is called Simian Films because she thinks you look like a monkey?

“She does think I look like a monkey, yes…”

“But she loves you nonetheless?”

“She loves me because of that.”

Ah, Hugh and Liz, Liz and Hugh… All we need are some beautiful babies for them to make a new royal family. I had, in fact, already asked Elizabeth if they wanted children. “I think we probably will, at some stage,” she said, “but sooner rather than later, because I’m 33. I can’t imagine not having children, and in the end, although he drives me demented, I can’t imagine having children without Hugh.”

Hugh, asked the same question, immediately wants to know what Elizabeth has said. When I tell him, he replies, “Well, I think I do, too, so we’d better get to it… I don’t know why we haven’t before. I suppose I’ve always had an inexplicable horror of settling.”

Like Peter Pan?

“No, not at all like Peter Pan. I think I’m just a bit of a glamour queen. I like the idea of flitting around the world, and not living in a semi-detached – not that that isn’t a lovely life, and not that I didn’t have a lovely childhood, because that’s how I was brought up.”

I point out that he and Elizabeth do not have to relocate from their splendid Chelsea townhouse to a suburban semi-detached in order to have children.

“Well, I suppose I’m beginning to realise that,” he says with a hint of a pout. “So I don’t have any excuses… I suddenly realised last Christmas that I can’t have another Christmas without having children. It’s just too humiliating, like not having a present for anyone – just too embarrassing… But I think I’ve blown it for this year, haven’t I?”

Still, he hasn’t quite given up the idea of Elizabeth giving birth on Christmas Day: “The Second Coming! The new millennium!”

Hugh Grant, as you may have guessed by now, is a handful: troubled, yet also flippant; a consummate flirt, yet also brotherly; a handsome heterosexual film star who occasionally lapses into the mannerisms of a homosexual heart throb. His relationship with Elizabeth reflects some of these inconsistencies: they lead quite independent lives (he describes himself as a “hermit”) yet there is a symbiosis in both their private and their business partnerships (and who else but each other could understand the perils and the pleasures of their ever-reflecting fame?) Hugh clearly adores Elizabeth, and finds comfort and security in their shared history – not just in the 12 years they have spent together, but in their separate yet mirrored childhood. “We are almost the same person,” he says, echoing a phrase she has already used about him. “Her mother is a teacher, like mine; her father is ex-army. We have the same sense of humour and had read the same books before we met, which is really creepy… People say we’re like brother and sister, as if we don’t fancy each other, which is just not the case. But we do have that fondness, that love you have for a sibling. If anyone says anything nasty about her, I want to smash them in the face, because that’s the way you feel about someone in your family.”

He, in turn, inspires great loyalty – or if not loyalty, then affection. “Poor Hughie,” was a refrain I heard often, from old friends who knew him at The Latymer School and then at New College, Oxford. Poor Hughie, they say, was anguished, melancholic, confused, foppish, sometimes funny, sometimes irritating, yet more often than not, totally engaging. No one who knows him well sees any similarity between his assumed on-screen character, and his real one. “They’re so different.” says Duncan Kenworthy, the producer of Notting Hill, when comparing Hugh Grant with his role in the film as William Thacker, the sweet, shy, bumbling bookseller who wins the heart of Julia Roberts (playing herself, more or less). “Hugh is wicked and wonderfully mischievous. The character he plays is not.”

In fact, it is a measure of Grant’s considerable acting ability that Notting Hill’s publicity line runs true: “Can the most famous film star in the world fall for the man in the street?” Well, yes, but only when the man in the street is played by Hugh Grant, himself a seductive film star adored by women the world over. As Grant declared waspishly, when derided for his acting talent in a game of charades with his friends Patrick Cox and Elton John, “I’m excellent at my job, that’s why I’m paid $7.5 million a movie!”

The trouble with all of this, of course, is that it’s hard to pin down who, exactly, Hugh Grant really is when he’s not pretending to be someone else. After the interview was finished, I ended up eating a curry with him at a local Indian restaurant, where he made me laugh a lot. But then, slowly, he seemed to lapse into melancholy and talked of recurrent nightmares about being possessed by the devil. I remember Grant’s story of his grandfather, haunted by that stern notion of honour and the desire to escape, and suddenly felt very sorry for him. When he left me back on the street where we had first met, and drove away in the big black Mercedes, I worried (fancifully, no doubt) about where he would end up.

The next day, prompted by several references he had made to astrology, I looked up his birthday (9 September 1960) in a book that both he and Elizabeth describe as “spookily accurate” about his character. “Life can be a constant battle for many people born on this day, against their fear and insecurities. Strangely enough, such fears can drive them on to be surprisingly successful. They often have to put themselves in positions of danger in order to experience the satisfaction of overcoming their fears. They must keep a handle on their wilder side, however, which can urge them to self-destructive behaviour not easily understood or condoned by those around them.” At the same time, this seemed to me to be an interesting discovery.

But maybe not. Several days later we spoke on the phone, and he was as cheerful, as charming and as clever as can be. “About that night,” he said. “You probably thought that I was really gloomy, like some kind of manic depressive. But I wasn’t. I just had a stomach ache, OK?”

This article was originally published on British Vogue.