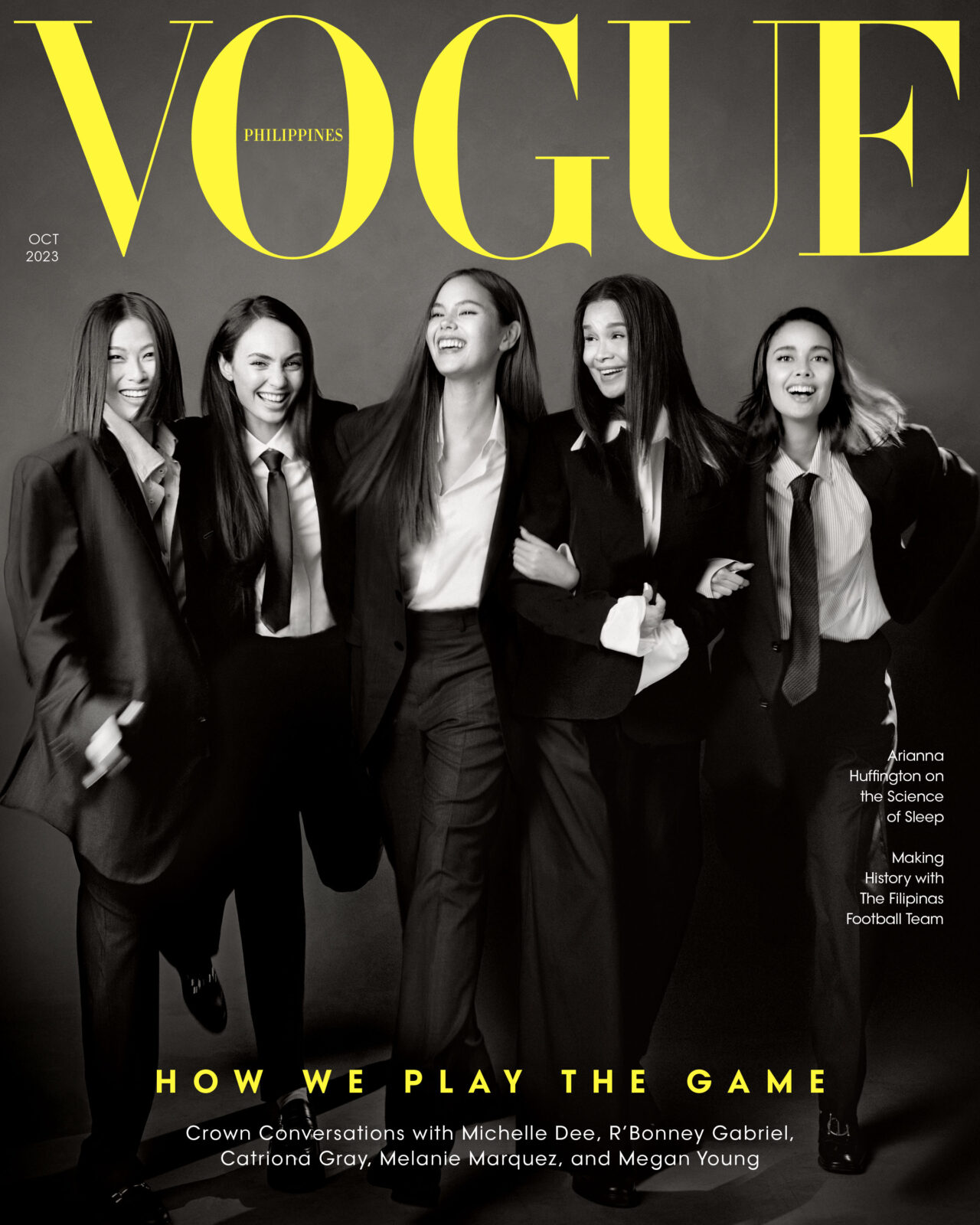

Photo courtesy of ANI PAYUMO

After moving to Spain, Ani Payumo receives the same diagnosis that her family has had to grapple with for years, but finds strength and beauty in the women that came before her.

“I should do The Camino,” I thought during a restless morning meditation. I was in search of a spiritual kick-in-the-pants. I figured a challenge—like a solo trek across Northern Spain—could be just the thing I needed for spiritual rejuvenation.

That same afternoon, I received a call from the hospital. In rapid Spanish, the voice at the other end said, “We’ve received the results of your scans. When can you come in for a biopsy?” Startled and numb, I spat out a random date, slid to the floor, and went on an emotional free fall.

A week and a battery of tests later, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. Two lumps in my right breast, relatively small ones, but of the aggressive kind. I was told I would need the whole suite of treatments—chemotherapy, surgery, radiation, targeted therapy, and hormone therapy. It would be a slog.

A cancer diagnosis, in a brand-new country, with a health system I didn’t know how to penetrate, in a language I was still struggling with. I was brought to my knees. I had embarked on my Camino.

Eckhart Tolle says there is great opportunity in illness. I believed that. Despite the terror I felt, I knew there would be great learning on the other side of this. I was determined to learn every lesson and to evolve into the spiritual being that I was meant to be.

In the ensuing days, I ransacked my library for guidance from spiritual leaders whose teachings have helped me time and again. Through them, I found strength and a strategy to face what was coming.

I eventually learned to manage my fear. Zen Buddhists say that bravery is looking directly at what is frightening us. Rather than succumbing to an unraveling, the spiritual path is to keep stepping into what terrifies us. So, I became acquainted with my fears. I listened to the stories of women who have trodden this path; I visualized myself bald and breastless; I did chores with only my left arm to simulate post-surgery limited mobility. And as was promised, fear ceased to hold me in its palm. I became open and curious. Where will this experience take me? Do I have the strength to handle this? What kind of person will come out on the other side?

My sister asked me, “Are you scared?”

“Not at all.”

That was the truth. Potentially devastating news—aggressive treatments, severe side effects, early menopause—fell on me like a feather. No impact.

I also learned to manage hope. Stoic philosophers say that virtue is having control over our minds, which is, in truth, the only thing we can control. Govern our thoughts, and we will find strength. Suspend desires, and we avoid suffering. So, I gave up any ideas of control, and instead, allowed my diagnosis to unfold.

“Cancer is the battleground, and lipstick is the war paint. When illness turns life on its head, feeling beautiful, as trite as it may sound, offers a surge of renewed energy.”

My friends told me, “Let’s hope for the best results.”

“No, no hoping. That can only lead to disappointment. Let’s let this evolve as it should.”

Not trying to micromanage the universe brought tremendous relief. And it brought miracles I couldn’t possibly have orchestrated, in the form of human angels providing relief, guidance, emotional support, and translation services.

I felt spiritually-evolved, bullet-proof, and ready for anything.

So, when I was advised over and over again by my cancer-survivor friends that I should do things to feel pretty, it went over my head.

“It is important to feel beautiful,” they said.

“Noooo thank you,” I thought smugly to myself. “I’m here for the enlightenment.”

I was convinced that beauty and other frivolities had no place in a cancer diagnosis. As I had done with fear and hope, I was eager to learn how to release my attachment to the superficial. This was one of the hardest lessons that aging still hadn’t been able to teach me: to gracefully accept the incessant changes occurring in my body—the graying hair, the sagging jowls, the flapping arms. Instead of softening to them, my vanity raged against the changes. And as it goes, a lesson will keep repeating itself until it is learned. So here it was—cancer offering me the lesson anew. My body would transform markedly, and I was determined to finally learn to peacefully inhabit every bit of its evolution.

That was then.

Nine sessions of chemo later, I stare at my reflection in the mirror—the strange hair prosthesis, the puffy steroidal face, the cystic chemo acne. I am broken. I am unable to find peace with these changes. Despite the attempts to meditate away these emotions, I am anywhere but present. I am angry, I am sad, I don’t want to be here. “Forget enlightenment,” I cried. “I just want to be cute.”

The desire to feel beautiful during cancer is to harness the fight within. I saw it with my grandmother. During her cancer treatments, even in the worst of days, she made a commitment to elegance. That beauty translated into inner joy, which translated into an excitement for life, which translated into surviving another 29 years and outliving her three oncologists.

I see it with my mother. She takes delight in dolling up. After her chemo sessions, she dons her glamour, steps into a party, and becomes its life. Fifteen years after her first diagnosis, she is still going full-throttle.

And I see it all around me in the cancer center—women dressed attractively (some even in flowing dresses and high heels) as if attending a dinner party instead of going into a chemo session; exchanging tips on where to go for wigs, for eyebrow microblading, for the best skin creams.

Cancer is the battleground, and lipstick is the war paint. When illness turns life on its head, feeling beautiful, as trite as it may sound, offers a surge of renewed energy. It is the push that allows us to re-engage with all the marvels of the world. And in my opinion, marveling at the world is worth fighting the battle for.

I am learning that there can be no enlightenment without our bodies. The body is the theater for spiritual growth. It is precisely because we are in physical bodies that we experience and are forced to navigate competing desires: our hunger to be virtuous versus our carnal tendencies, our yearning for spiritual maturity versus our ego’s hankering to be pretty.

Yes, the destination on this Camino is still spiritual enlightenment. But I will make a detour to the dermatologist on my way there. Because while I inhabit this body, I am, and will continue to be, a raging work in progress.

[Editor’s note: The Camino de Santiago is a network of pilgrimmages to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, Spain.]