Photographed by Shaira Luna

Imelda Cajipe Endaya, KASIBULAN, and the making of feminist art in the Philippines

Imelda Cajipe Endaya and her husband Johnny, an economist, have lived in the same Parañaque house since they moved in during the 1980s. The home has witnessed their children growing up, move away, and returning with children of their own. Today, it is just the two of them once more, but the house feels anything but empty. Paintings and artwork occupy nearly every inch of wall space, while the outdoors is dense with plants that Mr. Endaya nurtures. A persistent cat, called Ming Ming by default, refuses to be ignored.

Cajipe Endaya has been making art since the 1970s, her social consciousness shaped by the turbulence of the times. As a Fine Arts student at University of the Philippines, she took part in protests against Ferdinand Marcos. While many of her relatives and friends began migrating to the United States in search of stability, Imelda chose to stay, convinced she had a calling to serve family and country right here in her homeland. As a young wife and mother, she devoted the formative years of her practice to questions of Filipino identity.

Printmaker Ofelia Gelvezon, who taught at UP, initiated Imelda into a world beyond silkscreen printing, the medium she was trained in as an advertising major. “My first prints were from the 1970s, “Dahil Sa Iyo, Marcos,” and it was not a very good print, I guess, but it was a record of what my thoughts were at that time, students in chains being tied up.” Other works she produced at the Philippine Association of Printmakers were “Buhul-Buhol,” which reflected on our colonial history, and “Kastigo,” depicting political prisoners held in detention camps. Her father later helped her build an etching press so she could produce editions of her intaglios at home.

Between 1976 and 1979, Cajipe Endaya created Ninuno, her most significant print series, now part of the Cultural Center of the Philippines collection. Combining printmaking techniques with typography and religious texts, she transformed images of Philippine ancestors drawn from colonial archives like the Boxer Codex into layered compositions that commented on what she called “the ironies of subjugation of the Indio.” After a decade of working primarily in print, she felt she had arrived at a sense of artistic identity, and began her era of painting.

The 1980s marked the institutionalization of exporting Filipino labor, initially conceived as a stopgap solution to high unemployment and later entrenched as national policy. Cajipe Endaya responded by creating works that addressed the phenomenon from the female perspective. “It was from the point of view of Filipino women who stayed home watching migrant workers come and go,” she wrote in a 2011 essay on the diasporic experience. Many of these paintings featured windows, capiz frames, nipa shutters, glass jalousies, through which women gaze outward. Some were deeply personal. “I was isolated as a wife, a mother and raising three children,” she recalls. “When I shared my work with women writers, they said I was feminist. That was the first time I heard about feminism, actually, so I began to read about it.”

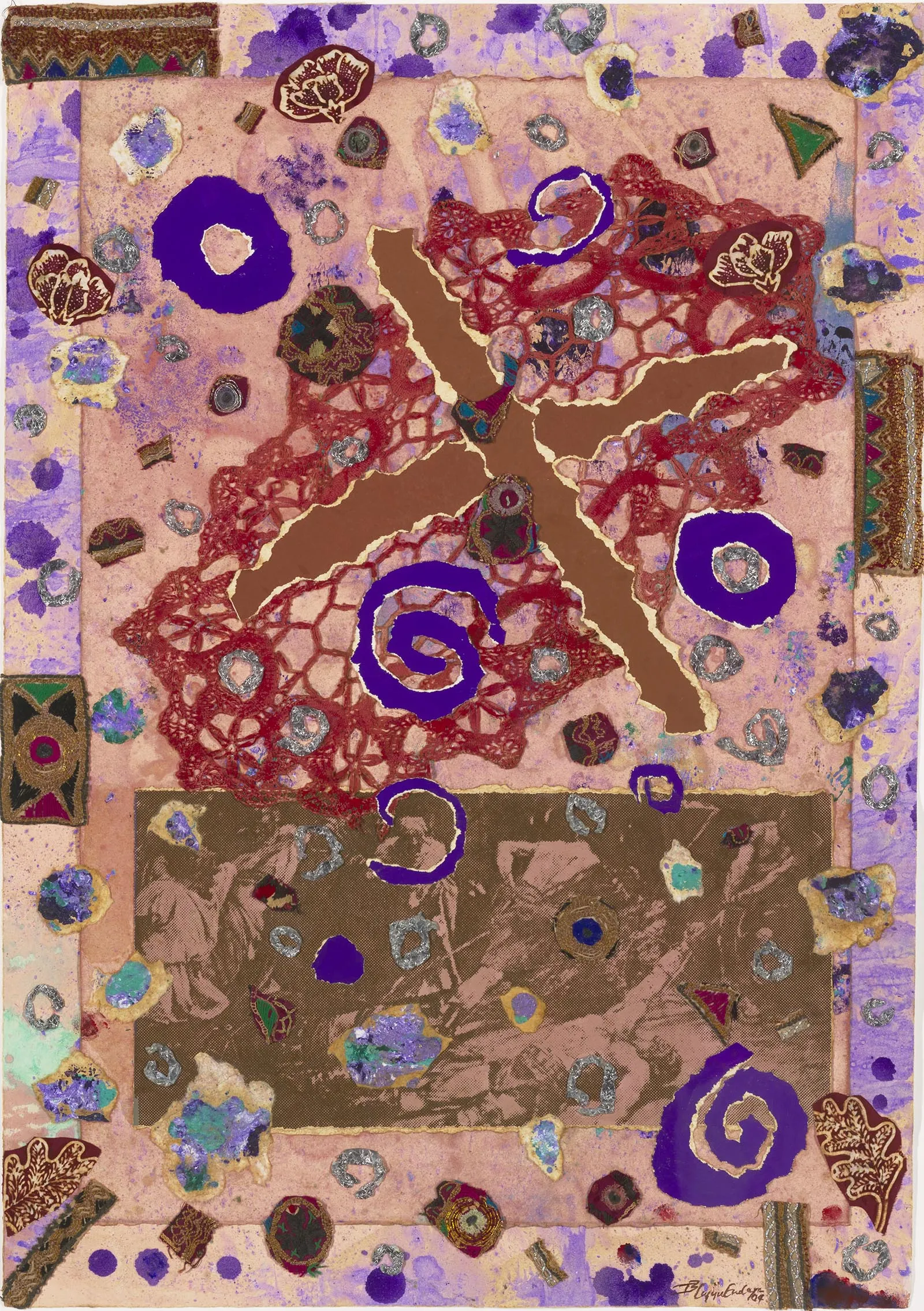

As political unrest intensified following the assassination of Benigno Aquino, Jr. and the eventual fall of the Marcos dictatorship, her work began to express more rage and grow more materially complex. Large scale textured collages made use of household materials, such as pieces of denim and her grandmother’s crocheted lace, glued onto panels of sawali (woven bamboo matting), choices that reflected both a commitment to indigenous craft, the work of women, and a practical reuse of found objects. Her involvement in women’s resistance movements eventually led to the formation of KASIBULAN (Kababaihan sa Sining at Bagong Sibol na Kamalayan), a collective dedicated to supporting women artists at a time when many of them were painting quietly in their homes with no opportunities to exhibit.

© Imelda Cajipe Endaya

Brenda Fajardo, one of KASIBULAN’s five founding members, once described the group’s early years as a “sewing circle.” Members brought varying degrees of feminist awareness, and their monthly meetings were largely about building a sense of sisterhood. “But that circle of sisterhood would traverse the domain of culture and polity as KASIBULAN built a body of work as an organization through its exhibitions,” Fajardo wrote in 2010. From the personal bonds of sisterhood the group began expressing solidarity with women at large, producing shows that explored themes like the role of the babaylan, the lives of Filipina migrant workers, and the heroines of the revolutionary period.

In 2005, Imelda mounted her last solo exhibit before relocating to the United States with her husband (a period of four years where they also lived as OFWs to some degree). Titled Conversations with Juan Luna and Walong Filipina, the show juxtaposed silkscreened fragments of Luna’s “Spoliarium”with elements from the works of eight women artists. As Fajardo later observed, the gesture was both an act of sisterhood and solidarity, weaving in women’s voices into a conversation that has long excluded women.

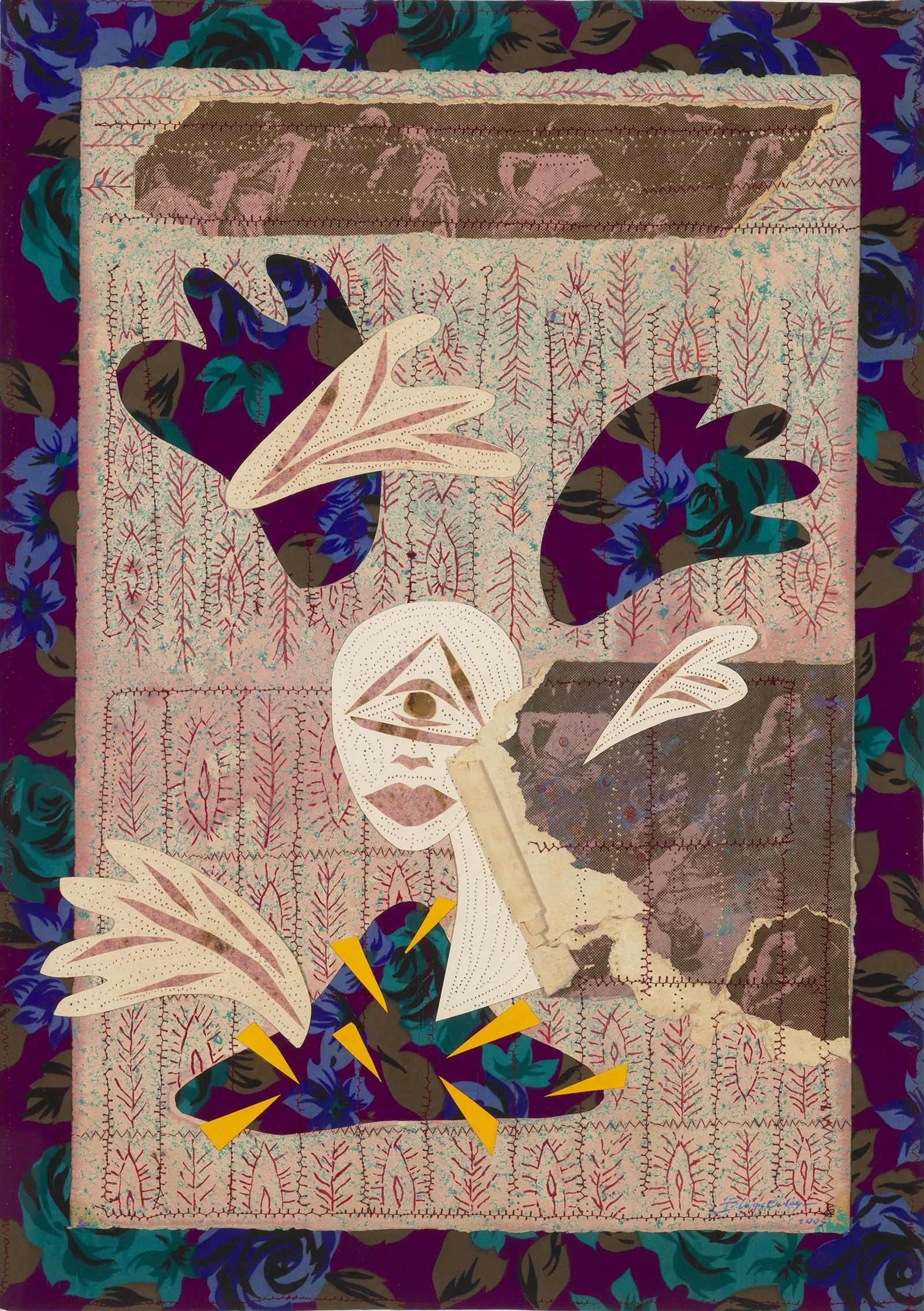

“I was comparing Juan Luna’s ‘Spoliarium,’ which is always regarded as the great masterpiece of a nationalist,” Cajipe Endaya explains, “but we have many works of women which are just as good, maybe not as large, but they are very good, expressing the feelings of women and the collective consciousness of women.” She shows us one collage from the exhibition featuring the sculptor Julie Lluch, also a KASIBULAN founder, holding a cactus heart, one of Lluch’s most recognizable clay forms.

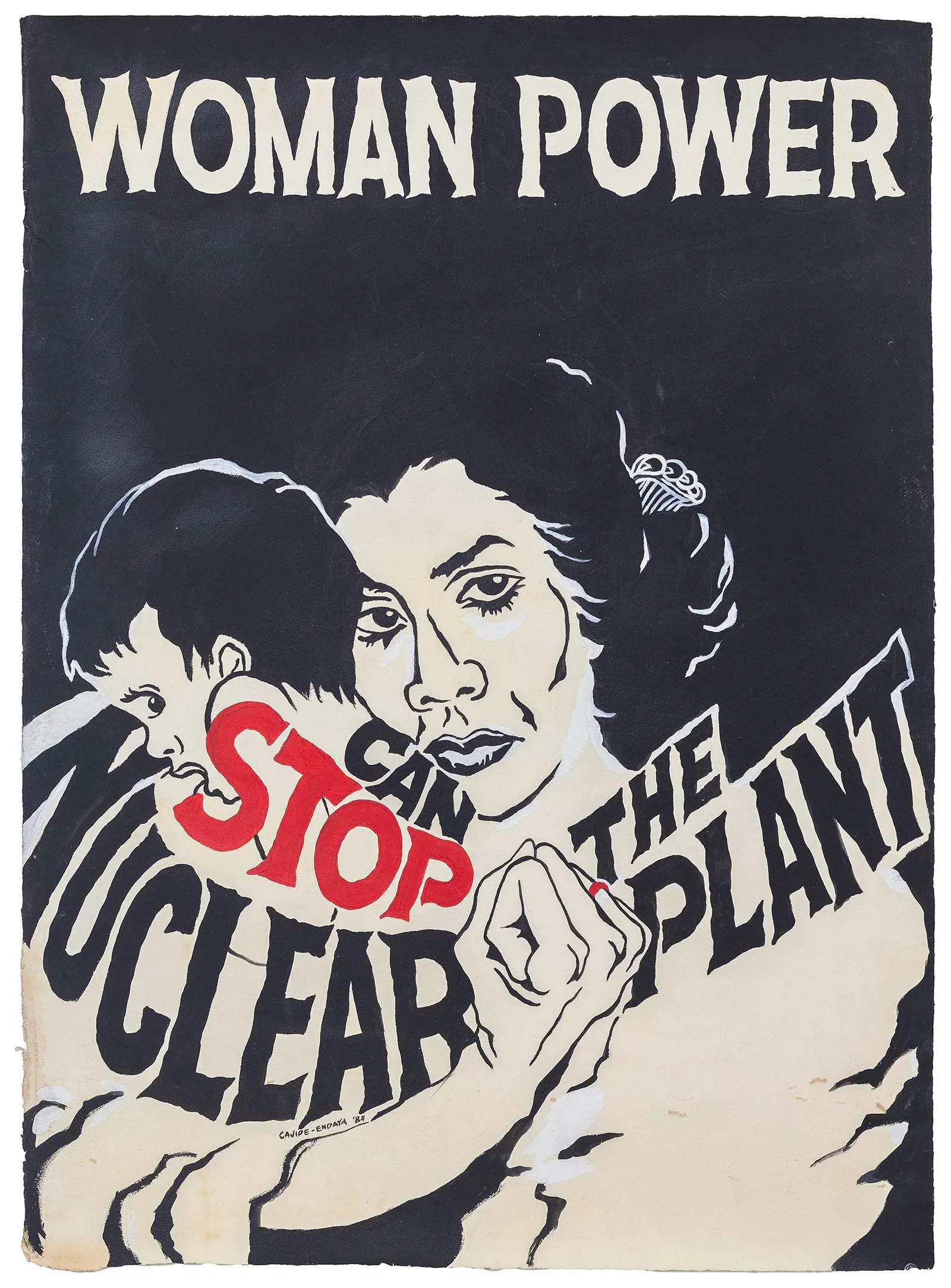

This year sees renewed attention to Cajipe Endaya’s work, whose themes resonate with particular urgency in the present moment. Opening January 9 at the National Gallery Singapore, Fear No Power: Women Imagining Otherwisebrings together more than 50 works by five Southeast Asian women artists. Included are Imelda’s 1981 painting “Buhay ay Vodavil Komiks”as well as a protest poster opposing the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant. The exhibition is NGS’s first to connect the practices of women artists across the region and examine how they use art to respond to social injustice.

Also in January, Silverlens presents Kahapon Muli Bukas, a solo exhibition that returns “Filipina: DH” to Filipino audiences for the first time in three decades. The 1995 installation, composed of black suitcases, maids’ uniforms, and cleaning tools, was created in the same year Flor Contemplacion was executed in Singapore. The piece, which traveled all over the world as part of an exhibition organized by the Asia Society in New York, was barred from being shown in Singapore when the controversy was still raging.

Inside Cajipe Endaya’s house, the entirety of which she considers her studio, stand two striking triptychs that one can’t help view in terms of each other. “Panimula” (2014) is a swirling mythological origin story of the bird Manaul who pecks open the bamboo from which the first woman and first man emerge. Nearby is “Bangungot ng Mabuting Pastol” (2017), made during the height of the extrajudicial killings. Skeletons, graves, and writhing beasts dominate the three panels. “It’s my Duterte piece. It’s a monster,” she says. At the top of the heaping pile is a man in white, the Good Shepherd who watches over a single lost sheep. “I still want to bring out hope, and the good in each of us,” she says. One triptych tells of creation, the other of destruction, yet both express the deep love she has for her country.

Imelda has always intended for her art to be accessible. She remembers speaking with the security guards during a retrospective at CCP and discovering that they were able to discuss and understand what she had to say. For her, that defines love of country. “Offering whatever good you can do, so that it can be appreciated by ordinary people.”

Cajipe Endaya’s gentle demeanor belies the inner fire she has tended as she poured her thoughts, her soul, and even the contents of her home onto her canvases all these years. Each new decade may bring a fresh hell, but she counters it with an instinct of hope, even joy. She has seen the rise of Filipino women artists as KASIBULAN continues its mission, and she still fervently holds faith in the transformative power of women who band together, in sisterhood and in solidarity.

In Manila, Kahapon Muli Bukas will run at the Silverlens Gallery from January 10 to February 14, 2026; and in Singapore, Fear No Power: Women Imagining Otherwisebrings will run at the National Gallery Singapore from January 9 to November 15, 2026.

By AUDREY CARPIO. Photographs by SHAIRA LUNA. Deputy Editor TRICKIE LOPA. Producer: Julian Rodriguez. Multimedia Artist: Mcaine Carlos. Media Channels Producer: Angelo Tantuico.

- Mapping New Currents: ART SG and S.E.A. Focus Anchor Southeast Asian Voices

- Art in the Cloud: 24 Hours at Khao Yai Art Forest With Trickie Lopa

- Rising Art Stars Mandy El-Sayegh and Korakrit Arunanondchai Lead ART SG’s Talks

- The Lubi Art Project by Silverlens Gallery Features Art Crafted with the Island