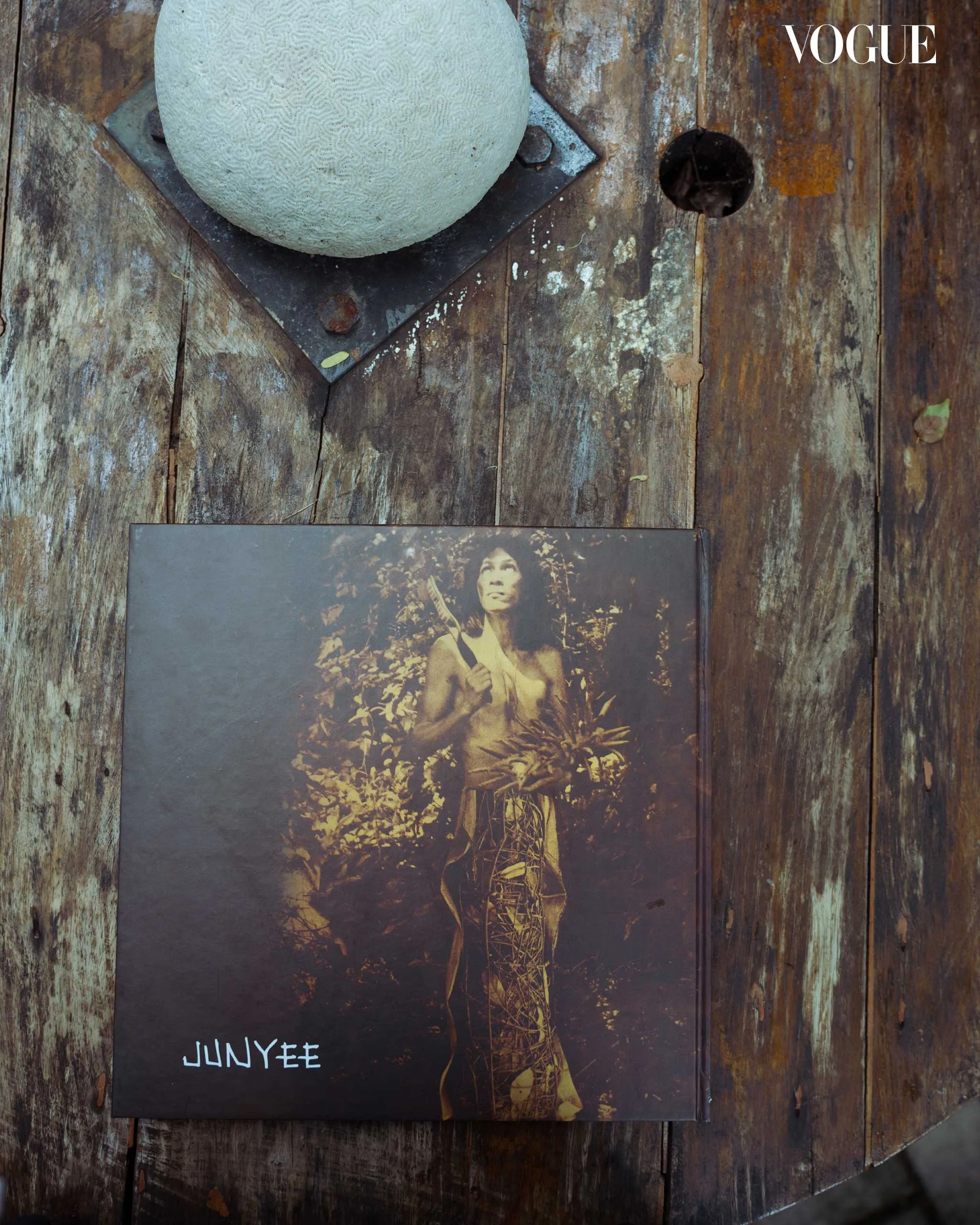

Junyee. Photographed by Kim Santos

In Los Baños, Laguna, Philippine installation art pioneer Junyee, or Luis Yee Jr, still keeps his hands busy.

It is apparent that Junyee, or Luis Yee Jr., does not like wasting his time. Shortly after arriving at the University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB), he immediately launches into a speech, giving a tour of his Sculpture Garden. There stand many of his most recognizable pieces: “Abortion,” a floor-based piece in the shape of an ovoid nest; a sculpture of his favorite dancer entitled “Martha’s Dance;” and the bamboo trellis “Balag.”

“These are interpretations made by other artists of the works I’ve made throughout my career,” he says, walking on the stone pathway. “Sorry ha, mayabang kasi ako [Sorry, I’m boastful],” he jokes. It doesn’t seem that way, though. There still seems to be a tinge a humility in his words even as he talks about his accomplishments throughout the decades: the Gawad CCP award, the 12th Paris Biennale, the inaugural Asia Pacific Triennial, and more. He is also a pioneer of installation art in the Philippines and a nominee for National Artist.

“I was born an artist,” he repeatedly says throughout the day, as he takes us through each chapter of his life. At the age of nine, the Mindanaoan artist had already won his first art competition. “It just came to me normally,” he shares. “It was there, and I liked it. It’s like an addiction for me.” Nothing could stand in his way, not even his own father. When his father opposed his passion, Junyee did not hesitate to leave home to pursue it. “I love my father, but I just cannot help being an artist,” he says.

After arriving alone in Manila, he was invited by sculptor Napoleon Abueva to be an apprentice. While he was studying at the University of the Philippines-Diliman (UPD), he spent three years on campus living with the late National Artist for Sculpture. “It was a very fruitful, happy year in my life as an artist. Finally, someone took notice of me,” he says.

He shares that he learned more from Abueva than he did in college. “I realized when I was there that an artist doesn’t need a diploma,” he says. He also opens up about his dyslexia, which made traditional schooling more difficult for him. “It’s very simple. I’m an artist; I do my work,” he says. When asked how he was influenced by Abueva, he answers that he was not influenced by his work, but by how his mind works. “[He] had a lot of tricks up his sleeve,” he says. “The cunning mind that is not satisfied with what he is doing now.”

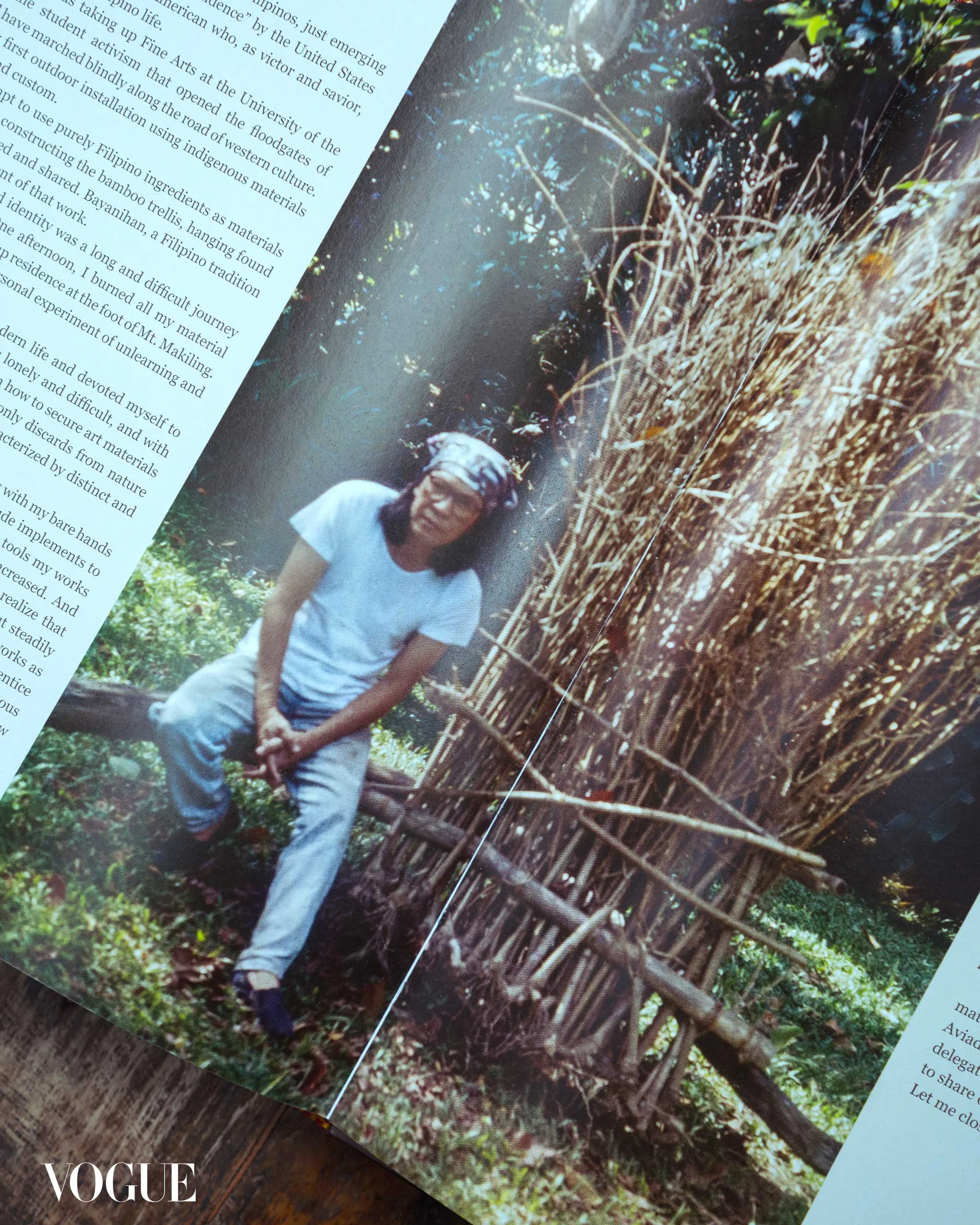

As an artist, his philosophy is guided by looking into what is Filipino. “When I was in college, the whole library was Western art. Why is all art taught in the Philippines Western? ” he asks. His practice is a journey into learning more about the country and its culture. Recognizing that all cultures worldwide are shaped by their surroundings, Junyee began by creating with natural and indigenous materials. “When I was in high school, I started practicing not harming anything. Even now, I don’t cut trees. I don’t pick flowers. I respect everything from nature,” he says.

“Angus: A Forest Once,” one of his most popular works, is an installation made from tree trunks with holes drilled into them to haul logs from the mountains. Meant to be a firm statement about the environment, the installation is not just art but also evidence of how humans abuse nature. With the temporary nature of installation art, this also highlights an integral part of his philosophy: that the message should transcend the artwork itself. Because to him, art is, first and foremost, a calling.

“Art making is not a way to make a living,” he says. “Once you think that art making is a way to make a living, you will become a businessman.” That is, art becomes merely a means to earn a living, rather than a practice, discipline, or passion. To him, when artists create to sell, art loses its meaning and impact; artists lose their voice. There have been times when he refused commissions (even though he needed the money) because they didn’t align with his values. “An artist is not a follower,” he firmly says. “You do it because it is necessary. It is you; it’s in your blood, it’s in your spirit.”

He cannot help but continue to be an artist. At 83 years old, he continues to work six days a week. “It’s like going to the toilet,” he jokes. “You can’t help running to the toilet because you have to go there.” Inside his home, his sculptures, furniture, paintings, and sketches fill up the spaces. And there’s more to come from his hands, for as long as he can make them.