Patrisse Cullors. Photo by ali reza dorriz

Inspired by quilts, the North Star, and a poem by Nissi Berry, these bags hope to inspire a new generation of abolitionists.

“I’ve traveled to multiple continents with the bag, and I can’t tell you how many people have stopped me to tell me, that’s such a beautiful design. What is that?” Patrisse Cullors says. “It’s such a conversation starter.” The bag in question is a square-framed woven rattan knapsack with a prominent star bursting forth, striking in its simplicity, like a beacon on one’s back.

The conversations Cullors hopes to ignite with this bag can go deep and they can be heavy, with big concepts like abolition and “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” That’s quite a lot to unpack with this bag.

Cullors co-founded the Black Lives Matter movement and is a long-time abolitionist organizer who has been on the front lines calling for the end of prisons and the end of policing. Also an author, artist, and educator, she has been focusing her energies on creating art in the years since getting her MFA. Her work is still political and confrontational, dealing with the issues she has devoted much of her life to: In 2020, she joined a coalition of other artists and activists in sending up sky-typed messages using a fleet of airplanes. Her message, “CARE NOT CAGES,” streamed over the men’s prison in downtown LA.

Along with noé olivas and ali reza dorriz, two friends from art school, Cullors opened the Crenshaw Dairy Mart, a community art studio and gallery in Inglewood, South Los Angeles. The CDM has become a vital space in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood for black and brown artists to address social justice issues. One of its programs is the Abolitionist Pod, a geodesic dome containing a self-sustaining garden, placed in neighborhoods with no access to fresh produce. The CDM is a space dedicated to “ancestry, abolition, and healing,” and it is there, during the frenetic week of the Frieze art fair, where the bags will be launched. Profits from each bag sold will directly help the previously incarcerated black women that the system has failed to support.

Rita Nazareno, the creative director behind accessories label Zacarias 1925 and her family’s S.C. Vizcarra weaving workshop, recounts how she was in Los Angeles and a friend, who owns one of Rita’s delightful Be Bags, wanted to introduce her to Cullors. “I was like, is it the Patrisse Cullors? Because I was at the LACMA the day before for the opening of the Black American Portraits exhibit,” Nazareno says. “It was one of the more powerful exhibitions I had seen. And I just had experienced this beautiful painting of Patrisse at the exhibit. It was called Big Chillin with Patrisse.”

When Cullors learned about the history and lineage of the S.C. Vizcarra workshop, she immediately felt that they could create something beautiful together. The women met over what is described as a magical evening of conversation, and they set to work on a collaboration, meeting over Zoom ever since. “I love fashion,” Cullors says. “It’s not something people really know about me, it’s not what I’m known for. But I do love fashion and I love meeting people at the intersection of fashion and art.” The North Star Project was born, with the bags as the first in a series of art and fashion pieces that Cullors will create to raise awareness of black women incarceration and speak to the resilience of their communities.

Following the North Star helped enslaved Africans make their way to freedom as they escaped under the cover of night, without any navigational aid except for the night sky. Patterned quilts, hanging from a clothesline, were also believed to deliver secret messages along the Underground Railroad system, warning fleeing slaves of danger or directing them to the next safehouse.

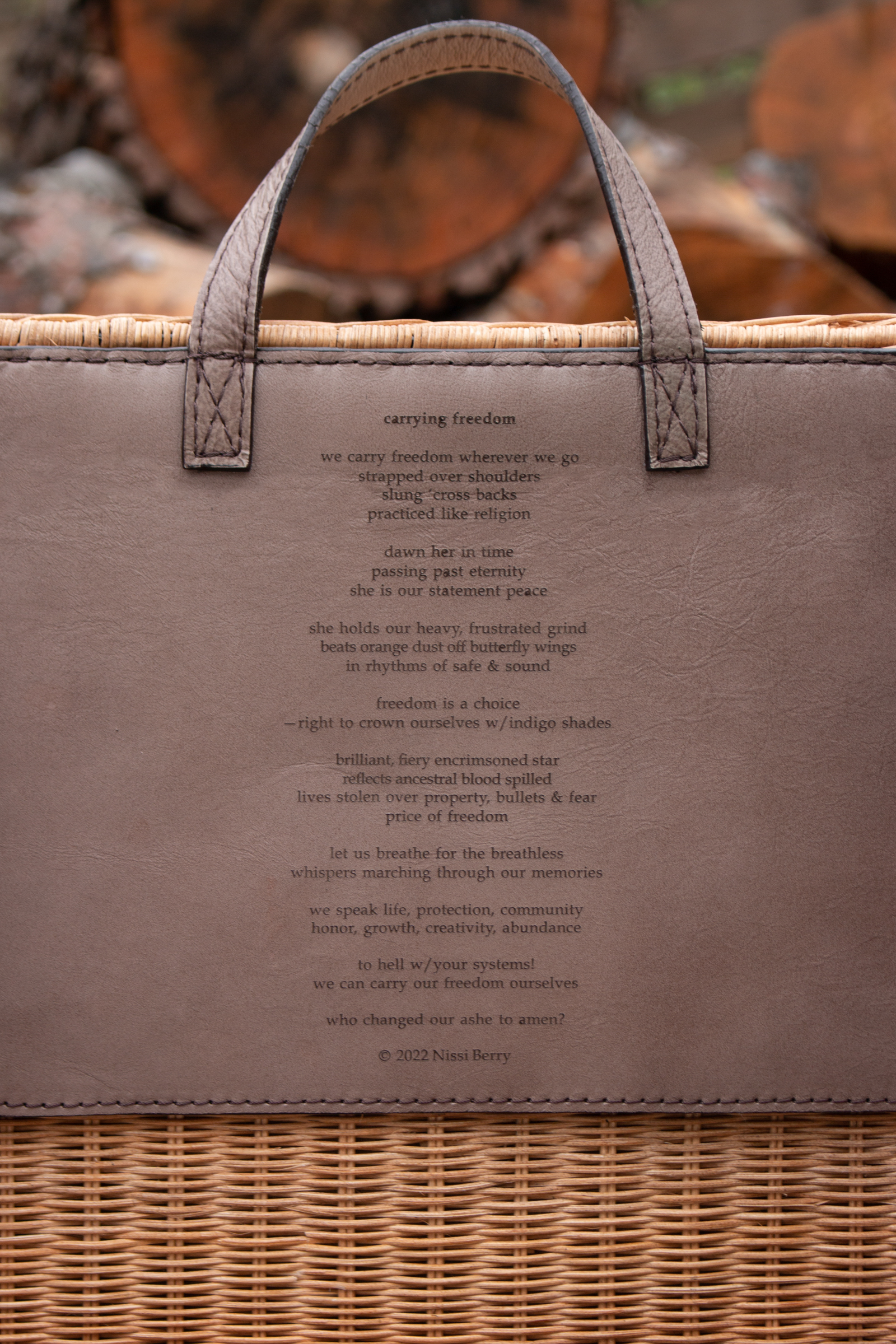

The bag, evoking a quilt patch, summoning the North Star, is also embedded with another type of code: poetry. The third collaborator in this project is the poet Nissi Berry, whose poem carrying freedom is laser engraved on a leather panel at the back of the bag. Berry, a formerly incarcerated woman and mother, describes how she wrote the piece: “I just wanted to embody the idea of freedom. I thought about Nina Simone’s ‘I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to be Free’ and how she sang it with her entire being,” she says. “And that’s how I wanted to write the poem, with my entire being.”

In less than a hundred words, Berry’s poem takes us through the flight from slavery, the taste of freedom, and her people’s continuing fight to breathe. Berry shares how the most painful part about being incarcerated was being separated from her children. “Being in a place filled with women, many of whom are away from their children and just thinking of how many children were without mothers also made me think of enslaved African women and how they were probably separated from their children.”

With Berry’s poem, the bag is transformed into a receptacle for freedom, or the things that freedom represents. The idea of the freedom bag is that it carries you to freedom as much as you carry it. Say Cullors, “You could fit a book, you could fit cannabis in this bag. Like, what are all the things that you could fit in the bag that will make you feel free?”

The limited-edition series will be launched on February 9 with a conversation between the three creators at the gallery space. “This project ties directly to that ancestry, healing, and abolition through line,” say Ashley Blakeney, CDM’s executive director. “These are conversations and projects that are really, really relevant to black artists and to our immediate community.”

The relevance extends beyond their immediate community and into ours. The dark links between police violence in the US and the Philippines can be traced back to the American colonial era, when the Americans developed surveillance techniques to suppress Filipino resistance, tactics which made their way back to the US. The Americans also turned Bilibid prison into a showcase of their “benevolence,” rehabilitating inmates through handicraft programs. The famous wicker Peacock Chair, associated with Black Panther leader Huey Newton (and several other pop cultural icons), has carceral origins, woven by Bilibid prisoners in the early 20th century. At the time, the prison was quite the tourist spot for furniture shopping, and the iconic fan-backed rattan chair produced by Filipino inmates was in fact originally known as the Bilibid Chair.

Cullors and the abolitionist movement asks us to imagine a different world, one where systems that rely on punishment is replaced with systems rooted in dignity and care. The North Star bags weave wicker and poetry, women and history together in way that she calls “abolitionist aesthetics,” which she explains is a way of looking at art and culture as a place to aestheticize abolition. “When we think about fashion, the art world, or culture, so much of it is centered around patriarchy, white supremacy, homophobia, classism,” she says. “I believe we should be bringing in the conversation of abolition wherever we go. We should be talking about it in fashion, we should be talking about it in art, we should be talking about it in film and entertainment.”

It’s a movement that may not be realized in our lifetime, but Cullors believes they’re gaining momentum. “The mother of abolition, Angela Davis, once said that she never thought she would see a popular conversation about abolition in our lifetime,” she says. “And it’s happening.”