Photographed by Mcaine Carlos

Mich Dulce presents Nagsasalitang Ulo, a manifesto of twenty hats that reimagine Filipino heritage and identity through form.

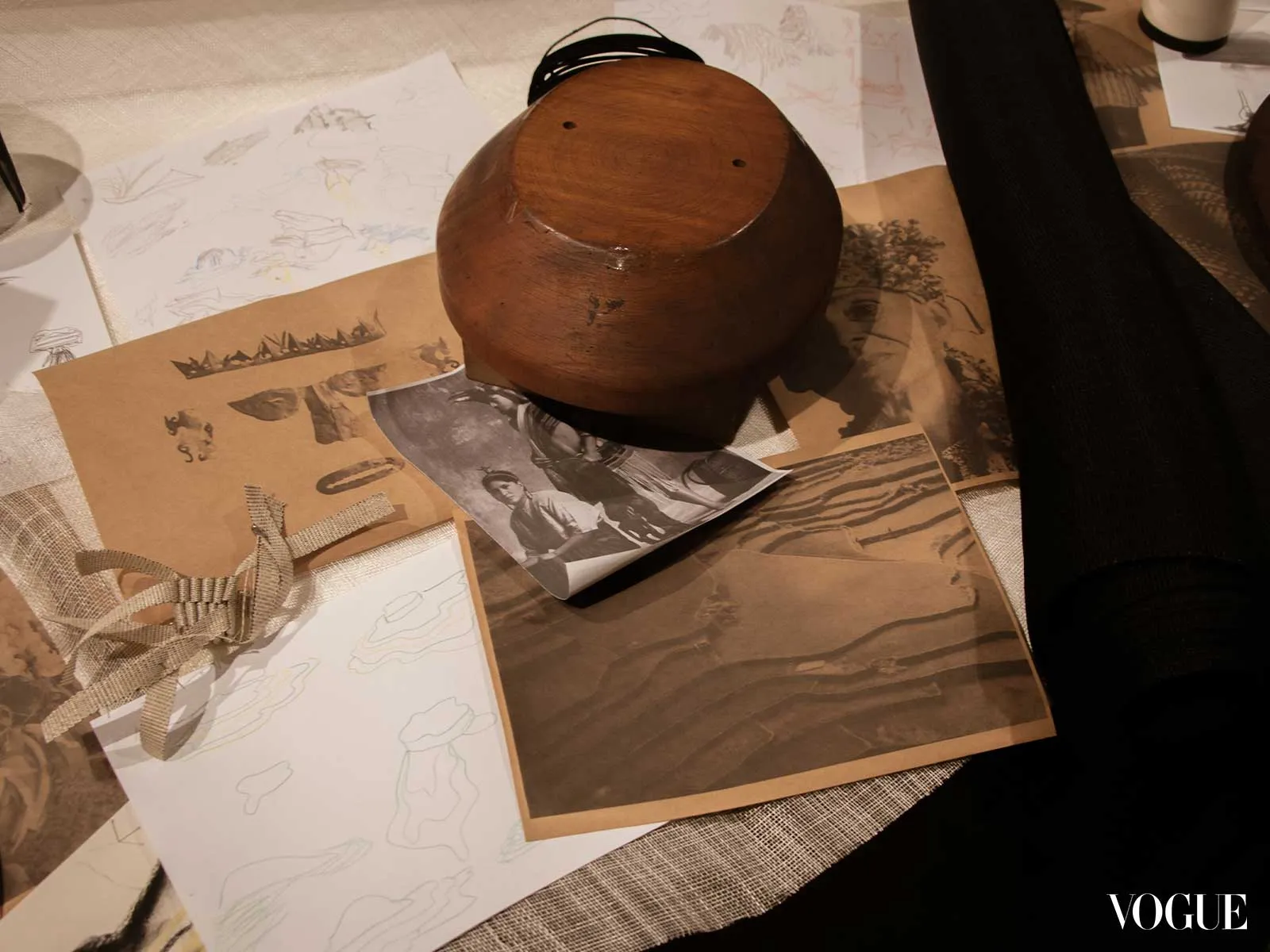

At Finale Art File in Makati, Mich Dulce unveils Nagsasalitang Ulo, an exhibition she resists calling a collection. Instead, she presents it as a narrative of form, memory, and heritage, shaped over the course of a year through research into Filipino identity, geography, and tradition. More than an exhibition, it is both a homecoming and a reclamation. “My artistic work is normally biographical,” she explains. “But over the past two years in London, working within the Western millinery ecosystem, I really want to challenge myself and think about how to decolonize millinery. Because it’s all Western, right? Traditionally, my work, if you see my old work, it’s all using British shapes. What I want to do now is use the Western materials, but really do research to think about our geography, our culture, and our traditions. What is a shape that’s Filipino?”

Her journey to this point is one of discipline and curiosity, moving fluidly between creative identities as designer, musician, activist, and mentor. Her professional path took her into the ateliers of Western luxury houses, including a formative period working with Chanel, and she is now an industry mentor for the Chanel and The King’s Foundation Métiers d’Art Millinery Fellowship, a program training the next generation of milliners. “So I’m the industry mentor for that program,” she says, almost offhandedly. She also works with master milliners in the UK such as Noel Stewart, contributing to projects including Demna Gvasalia’s 53rd couture collection for Balenciaga. “It is really like I am within the Western millinery ecosystem,” she says, “and I kind of have a little bit of an identity. Not a crisis, but I really want to think about my place in it.”

Nagsasalitang Ulo, literally “Talking Heads,” with a subtle nod to the American rock band, deepens her inquiry into what a Filipino hat can be. Each piece, she insists, is not only an object but a speaking form, a counter-archive that gathers memory and landscape into material. She begins with questions: what forms do we recognize as Filipino? How can millinery, long steeped in Western archetypes of the boater, the fedora, the cowboy hat, be decolonized to reflect Philippine shapes, landscapes, and traditions? “Since before I am always using Filipino materials but in Western forms,” she says, “this time I want to push further and research not just the materials, but the shapes, the memories, the rituals.” The process takes her across regions and through archives of memory, oral histories, and everyday experience. She describes her research as “super serious,” yet the hats radiate playfulness and love of place.

Displayed in the white expanse of the gallery, the hats float like voices suspended in air, twenty talking heads that each tell their own story. The salakot, a hat deeply tied to Filipino culture, serves as her starting ground. “It’s the archetype,” she says. “I want to interpret it in a modern, contemporary way.” A piece she calls ‘Pagsanjan Falls,’ sculpted from PETG plastic, evokes the movement of water. “When I come here, I go swimming. I want to make something really fluid, inspired by our ecosystem.” The ‘Bahay Kubo’ hat was handmade with buntal. “I really wanted it to look like it was floating on top of the cap,” she explained, mimicking the silhouette of an Ifugao house. Another hat translates the ‘Banaue Rice Terraces’ into form, a challenge so technically demanding she learns woodworking in order to carve her own hat block in London. “Each hat needs its block,” she explains. “So for the terraces, I have to learn to saw and make a block in the shape of the exact terrace. I’ve never done that before.” For Dulce, the discipline is instinctive, if the tools do not exist, she teaches herself to make them.

Other hats reference the woven banig mats found throughout the archipelago, each region with its own distinctive patterns, materials, and traditions. A piece inspired by Cebu’s gold death mask draws from archaeological finds, covering only the eyes with a glinting metallic sheen, a symbol of wealth and spiritual protection. Another reimagines the gumamela, recalling childhood play. “When I was a kid, you pound the gumamela and you would make bubbles. I want to capture that memory.” The scent of sampaguita is also present, embodied in a hat that nods to the garlands sold on Manila streets. “We really want to make sure to represent it. It’s such an iconic form, when you go to the Philippines you always see vendors with their sampaguita.”

‘Tangkulu’ references pre-colonial headwear traditions of wrapping flat textiles around the head to create volume and shape, and Dulce mischievously adds a black veil in homage to fashion critic Diane Pernet. A ‘Palm Sunday’ hat uses the weaving techniques of palaspas, stiffened into radiating fronds. The ‘Tabungaw,’ inspired by Ivatan traditions of hardening gourds into protective headwear, is by her own account “the hardest one to make” because of the technical demands of stretching latex over form. The ‘Samar’ hat translates the dramatic rock formations into curved domes. From Quezon’s Pahiyas Festival, she takes inspiration in stiffened leaves, creating a festive headpiece that echoes the riot of color that fills Lucban’s streets every May, and the ‘Vakul’ hat references vuyavuy palm in ostrich feathers. Together, the twenty hats form an archipelago of silhouettes, each distinct but all linked by what Dulce identifies as a Filipino curvature. “In that exploration, I realized that the shape of the Filipino hat is a little bit curved, dome-y. That’s so Pinoy pala.”

If the hats are talking heads in form, Dulce also wants her guests to experience them through taste and scent. She invites her friend Chef Jen Gerodias, whom she met in London and who now runs Casa Luisa, to create a menu in dialogue with the collection. “Usually when people come to see me, they try on their hats. It’s tactile. But because it’s a show, there’s no tactile avenue. I really want there to be a sensory experience that allows you to use all of your senses.”

Chef Jen responds with dishes tied directly to the hats’ inspirations. The Ivatan Bakul hat becomes a taro fritter wrapped in kadaif, concealing pork confit preserved in fat, paired with a sweet date reduction. “In Batanes, they preserve pork in jars, so I make a pork confit,” she explains. “The dates represent the date palm leaves.” The Gourd hat is translated into an upo pie, the vegetable treated like apple, caramelized with Ilocos salt, and presented in vessels shaped like hats. From Samar comes Moron, a glutinous rice delicacy flavored with vanilla and chocolate, topped with pili nuts that mirror the rugged terrain.

For Jen, the process mirrors Dulce’s. “Everything is inspired by the location of the hat,” she says. “It’s so interesting, the way different regions prepare food. From my research, I am able to apply it to the techniques that I know, and also the food memory that I have.” She approaches the menu as both research and remembrance, pulling from methods of preservation, layering, and flavoring that speak to local traditions. “When you taste something, it triggers a memory. I want people to feel that connection, to remember something about their childhood or their travels, the same way Mich is doing with the hats.” Each dish, she notes, is a dialogue between disciplines, making the hats edible, extending their stories into the body.

The culinary narrative is paired with cocktails developed with Santa Ana Gin, a Filipino brand distilled in France using perfume techniques and botanicals such as ylang-ylang. Marketing lead Monica Larkins describes the project as an extension of Dulce’s storytelling. “Together with Chef Jen of Casa Luisa and Mich, we put together cocktails inspired by places in the Philippines as well as her hats.” “Bola ng Gumamela,” made with hibiscus tea and calamansi, is bright magenta pink. “Very cute. Very girly. I love pink cocktails,” Dulce says. Sumpakita, from the phrase sumpa kita, or “I promise you,” is an aromatic interpretation of sampaguita. Iso ng Beer is the gin served simply on the rocks. For Gerodias, the pairings are as important as the drinks themselves. “You should have the hibiscus one with a moron,” she says. “The bitterness and sweetness, it goes really well.”

Every element, the hats, the food, the drinks, is part of Dulce’s intention to create an immersive vernissage where memory and identity can be tasted, touched, and smelled, not just seen. Even the music is chosen with care. “I want to do an indie pop, Belle and Sebastian, British pop kind of vibe. Very me. A mix of British and Filipino indie bands.” The setting, too, is personal. Finale Art File has hosted her before, and gallery director Dita has known her since childhood. “She remembers me coming to the gallery as a five-year-old with a giant bow on my head. This is my third show here. It always feels like coming home.”

Dulce also reflects on the materials that underpin millinery itself. She points out sinamay, the woven abaca textile that in the Philippines is often dismissed as mere gift wrap, but which is in fact the most widely used hat-making material in the world. “That’s actually what started my interest in hat making. When I am learning in Europe, everyone says sinamay, sinamay. And I realize it’s from here, from us. We don’t value it, but it’s the core material for hats everywhere.” The irony, she notes, is that while the Philippines is not known for its hat trade, it has long supplied the raw materials that sustain it globally. Reflecting on Nagsasalitang Ulo, Dulce is clear about its significance. “It takes a year to do the research. I feel really super happy because I really choose the right collaborators. The way Jen executes the food, it really manifests the concept of the show. I feel cathartic. I feel home.” What she has created is more than a showcase of craft. It is a manifesto for how heritage can be reimagined, how a milliner trained in the ateliers of Paris and London can return to Manila and sculpt the memory of place into form. Her hats carry not only the shape of the Filipino dome but the story of a woman who walks through the most rarefied circles of global fashion only to come back and say: the Filipino shape matters.

By LAWRENCE ALBA. Photographs by MCAINE CARLOS. Digital associate editor: Chelsea Sarabia. Additional interviews by Ticia Almazan.

- Odd Romance: Mich Dulce’s Intimate Ballet of Form and Flow“Raising Hope” in the spirit of International Women’s Month

- A Creative Middle Age: RAFGLANG and Mich Dulce Mark Their Runway Return at Bench Fashion Week

- For Mich Dulce, It Was Really ‘Craft That Was the Emphasis’

- Odd Romance: A Serene Moment in Paris with Nadine Lustre