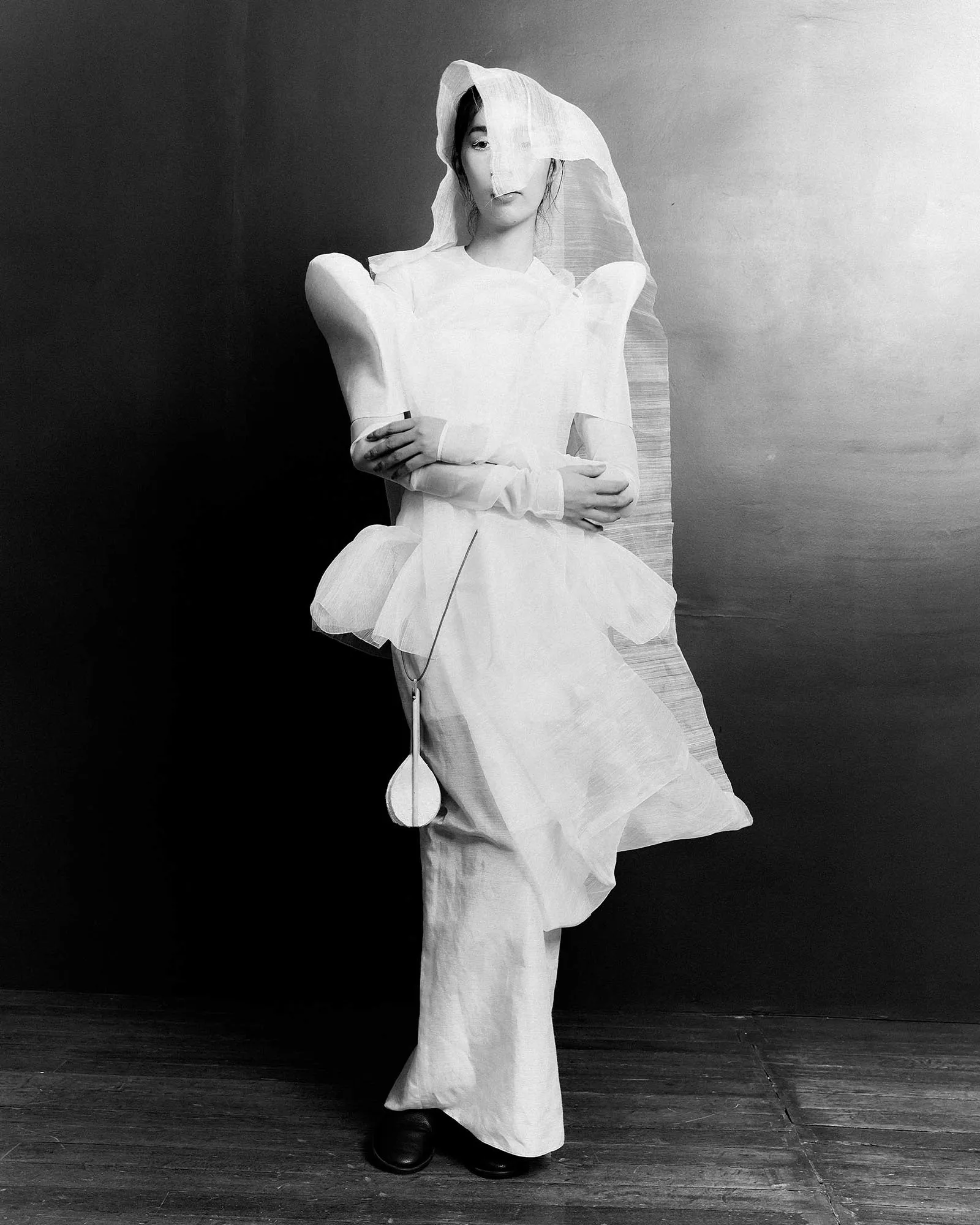

Photographed by Colin Dancel

The designer reflects on repetition, restraint, and the design logic behind Filipino formalwear.

Koko Gonzales designs in motion. Working between custom dressmaking and inherited silhouettes, the Filipino formalwear designer builds garments through structure and balance: how weight sits, how fabric moves.

A Gonzales look is marked by restraint. Peplums float at the waist, sleeves widen precisely at the pleat, fabrics are chosen for how they fall and settle.

Travel, in his work, often means circling back: to familiar fabrics, to silhouettes passed down through instruction or instinct. His latest collection, presented this week at Indonesia Fashion Week, follows that rhythm. It’s shaped by piña cocoon, softened moire, and the slow language of garments made by hand.

Best known for his bespoke label LSW, Gonzales works with precision. Edits are constant. Some sketches do not make it past the table. A single sleeve might be revised multiple times to achieve its balance. When tradition appears, it does so with clarity: wide terno pleats, barong references, lines kept clean. His language is rooted in place but not bound by it.

Ahead of his Jakarta debut, Gonzales spoke to Vogue Philippines about the routes his designs follow and the steady choices that define his work.

Your silhouettes feel deliberate, sculptural, pared back, and highly composed. Where did your instinct for garment-making begin? Was there an early influence or moment of recognition?

Thank you. [It’s been through] a lot, and many people helped, too.

My interest in clothes started when I was in elementary school. I remember not having anything to wear [between] grade school to high school. There’s that moment when your look starts to transition because you’re already in high school and you’re not supposed to look like a kid anymore. This was in the ’90s, and there were very few options. And, to be honest, I did not know much about clothes or where to find them either. So maybe my love for fashion began with the simple fact that I couldn’t find clothes I liked.

As a designer who works so closely with form and heritage, do you see your practice as part of a longer lineage, fashion as inheritance, or are you more compelled to reshape that vocabulary altogether?

The Philippines has a history that should be revived and remembered. [This practice becomes] my contribution [to that history]: promoting Filipiniana, joining Ternocon, and now, making this collection for Indonesia.

To be honest, I changed the terno sleeves I learned at Ternocon. Back then, we worked with [an] illustration board, or you could buy a wooden template. But for this new collection, I had four molds made by my carpenter. The sizing is still close to the original terno, but I widened the curve a little, especially at the end of the pleats. I wanted the shape to feel full, not flat.

I hope the spirit of the terno is still there. But sometimes I also think, who are we asking [for] approval from? Who gets to say if it is still a terno?

Many of your designs work in tension: between sharp and soft, between structure and lightness. What guides your decisions during the design process, and how do you know when a piece is complete?

I start with a sketch, then move to the fabric, or sometimes both at once. There is an initial sketch, then I [revise] it for the final version. While we were making the [recent] collection, [several] edits happened. We removed a vest, changed a pair of pants, and one design did not [even] push through because we ran out of time.

[Many] factors affected [how the collection turned out], but it was really on the shoot date that the final look came together. It still [resembled] the original sketch, but of course with some differences. Clothes really do change once they are worn by a model. There was one pair of pants I did not like at first, but when the model wore them, it suddenly worked.

Geof Gonzales [styled] this collection. He’s good. He is also the one who keeps [encouraging] me to sketch, saying, “Maybe you can still do this.” [His ideas] are inspiring, and what we make together is [always] fun when we bounce [things] off each other. “What about this? Can we do it like this?” There’s always something new, always [something else to explore].

This new collection will be shown abroad, but its language is very much your own. What set this body of work in motion, and was there a particular image, material, or internal shift that shaped it?

That is my current [creative] conflict: who am I? Am I defined by a specific aesthetic? By my use of fabric? What visual language do I speak?

[Right now], I’m [drawn] to soft fabrics. Since the direction is Filipiniana, I used a lot of silk cocoon. I mixed in some piña, but just a little because it’s expensive. There were heavier fabrics like moire, but I tried to make them feel softer by adding a film of bubble organdy or creating [more] roundness in the structure.

When designing for a context outside the Philippines, do you feel a responsibility for what the garments reflect, or is the act of creating already its own way of carrying meaning across?

For me, as much as possible, [it should] come from the Philippines. From the fabric, the terno shape, barong-inspired details, and the kimona. [That’s where I start to] play with the design. It’s what I know, and where I began.

I even have a book about the textile exhibit at the Ayala Museum, and while reading it, I realized how much I still don’t know. There is still so much to learn and experiment with in design. I’m still new as a designer, and I have probably already made things that people could say, “Oh, that has been done by someone else,” or “That has already been used before.” Sometimes it is hard when I focus on that, so now, I just try to enjoy the process.

Do you tend to start from fabric, structure, or feeling? or does the form emerge more intuitively as you go? Are there materials or rituals you return to often?

Fabric and sketch, and whatever I [already] know how to do, that’s where I start. But if you [saw] my sketches, they’re messy: a lot of [notes], erasures, layers. I even have printouts of each sketch, like postcards, sealed in plastic packaging. That’s what I always go back to. It’s a reminder of the process and [of] what it’s supposed to look like.

Throughout your collection, elements like the terno sleeve, an understated palette, and subtle fabric manipulation feel precise without being ornamental. How do you design for impact through restraint, rather than addition?

My designs are basic, but once we’re in the workshop, there’s suddenly so much to explain. What will the finish be? How long should it be from the waist? How much [should] we add when this is attached? Which layer goes outside, and which one underneath?

It’s all trial and error, then instinct: Do I like this? I need to like it. Sometimes, the idea is only in my head. I’ll have it made, but it won’t work. Other times, a wrong stitch turns out beautiful. So many things happen in the workshop.

TernoCon brought together designers with vastly different sensibilities. What did that experience open up for you in terms of form, tradition, or how you position your own work?

I’ve said this before in an interview; I feel like an outsider in fashion. But thankfully, at Ternocon, I met a lot of great creative people (and I learned a lot from them too). They were all inspiring because each one had their style. That experience was intense, to have your name announced at PICC, then your designs walk the runway.

After I joined Ternocon, I became more confident suggesting Filipiniana to my clients, even if they were just wedding guests, even if it wasn’t a Filipiniana-themed event. I want to normalize it so [it’s seen as something you can wear anytime], not just for formal occasions or costumes.

Do you think of clothing as a kind of travel: can garments take us somewhere or return us to something we’ve known, either for the person wearing them or for those encountering them?

Is that something [we feel as individuals], or [something embedded in us as] Filipinos? Why was Filipiniana forgotten? And why is it suddenly trending again? Why did it disappear?

There’s a story in clothing. Why did the sleeves get bigger? Why did the pañuelo disappear? Why are old elements being brought back now? Why are terno sleeves trending again?

If you look at the book Fashionable Filipinas, there are so many stories there about the evolution of the terno sleeves; you’ll see how it changed, disappeared, and came back again. You’ll learn so much if you go back to history.

Designer: Koko Gonzales of LSW. Stylist: Geof Gonzales. Photographer: Colin Dancel. Model: Belinda. Hair: Andy Del Rosario Porquez. Makeup: Sam Victor. Runway Music: DJ Mike Lavarez. Video Editor: Ely Caluag. Custom Fans: Jose Ramon Diokno Olives. Custom Jewelry: Eric Manansala. Shoot Producer: Myrrh Lao To. Production Assistant: Carlie Lajara. Venue: Sine Pop! Special thanks to Ibu Phoppy Dharsono, Hon. Gonaranao B. Musor, and Ms. Jollan Margaret A. Llaneza.

- The Pathfinder: Raffy Tesoro on His Mother, Designer and Textile Artist Patis Tesoro

- How Conner Ives Won The 2025 BFC/Vogue Designer Fashion Fund: A Behind-The-Scenes Look At The Judging Panel Day

- Designer Anthony Ramirez Is Reinventing a Philippine Weaving Tradition

- Interior Designer Tessa Alindogan Takes Style Cues from Design and Life