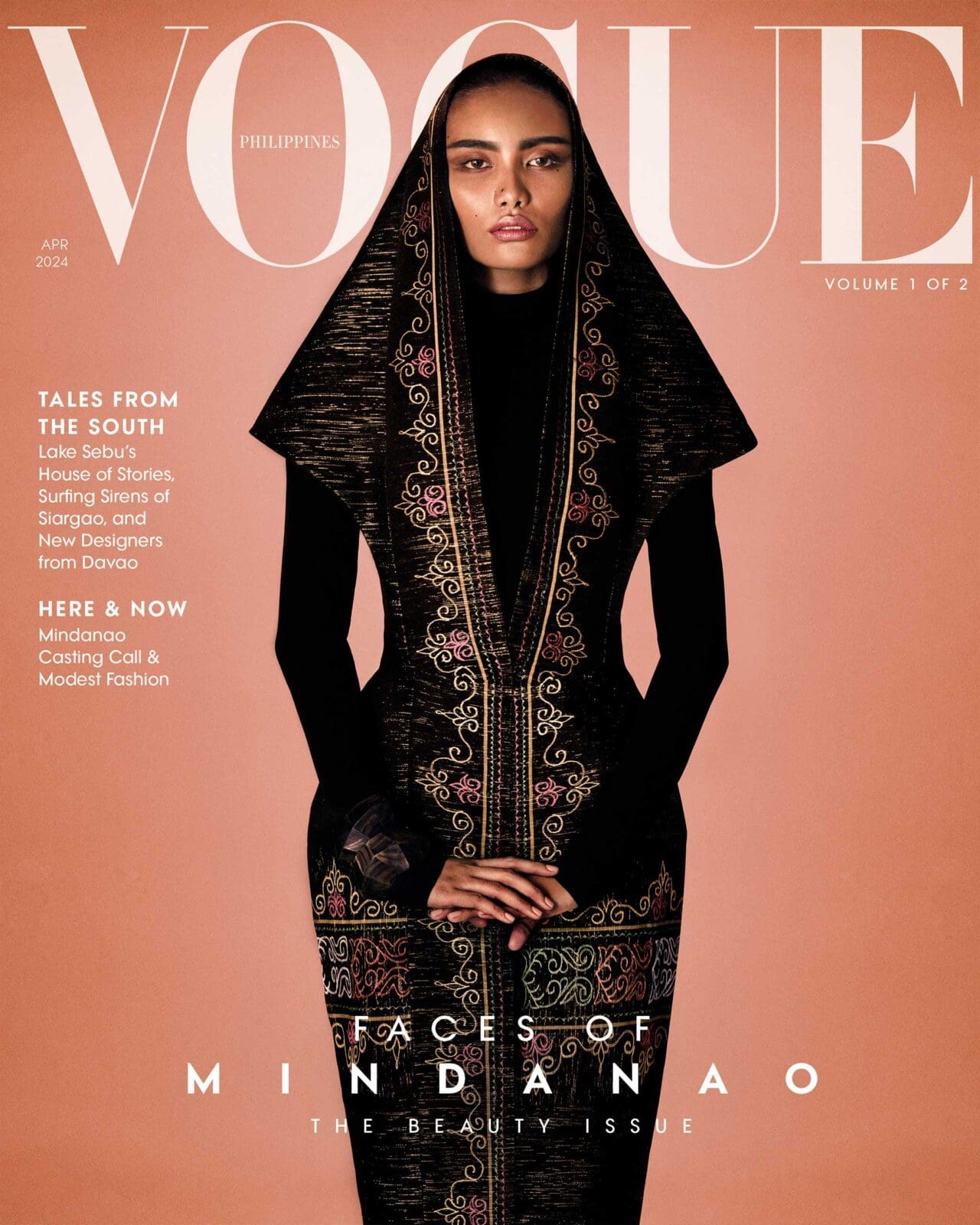

Photographed by JOSEPH BERMUDEZ for the April 2024 Issue of Vogue Philippines

As one of the emerging designers from Mindanao, Wilson Limon reimagines indigenous textiles to breathe new life into centuries-old traditions.

When travelers journey to the highest peak in the Philippines, it’s often in pursuit of an arduous, days-long hike. But that wasn’t the case for Wilson Limon, at least not in October of 2014: “I went to the foothills of Mount Apo to meet a weaver.”

Then a fashion design senior at the Philippine Women’s College of Davao, Wilson was working on his thesis project that required a reinterpretation of traditional attire. Each student in the program was designated one out of Davao’s eleven ethnolinguistic groups, and Wilson was assigned to the Bagobo Tagabawa. Coming into the project, he admits having “zero knowledge at all, even if I’m a Dabawenyo.” What began as an extensive Google search eventually manifested in a site visit, but not before he sent out letters to local government units to secure consent and guidance.

Upon arriving at Mount Apo, Wilson found himself before a simple house akin to a nipa hut. He recalls watching a woman weave on a loom, saying, “It’s very uncomfortable what she’s doing. But, you know, they’re really passionate [about it]. Because that’s their identity. That’s their prized culture. Sabi pa niya na pamana pa daw yun ng lola niya [She even said that weaving is her grandmother’s heirloom].”

Galvanized by the craftsmanship he witnessed firsthand, he chose to reinvent their abaca fabric for his thesis. Observing a lack of weaves in contemporary, everyday menswear, he started digitally printing the patterns on t-shirts and polo shirts.

The thesis collection ended up faring well among audience members; some pieces even sold right after the showcase. Post-graduation, after a slew of competitions, brand collaborations, and artisanal fairs like Manila FAME and ArteFino, Wilson joined the Bench Design Awards in 2017, where he found himself looking for collaborators. He recounts, “There’s a park here in Davao, parang may mga bahay-bahay, yung mga nagbebenta sila, mga ethnolinguistic groups [there are stalls where ethnolinguistic- tic groups sell their products]. From there, I met a Tboli artisan.”

Following a series of commissions with that weaver, Wilson finally decided to visit Lake Sebu in South Cotabato, where the Tboli are native to. There, he met even more weavers, and became immersed in their artisanal processes. “What I do is, number one, research,” he emphasizes, “I work with different communities. They have their different laws, so ideally, I study muna. For example, there’s a Blaan community in Sarangani. So, what are their strengths? Do they weave? Do they embroider?”

“Dismissing the title “designer,” Wilson instead uses the term “creative director.” According to him, he isn’t designing anything—the indigenous artisans are. His role is to reimagine the textiles they design and make; to put forward interpretations of it that they might appreciate.”

Over time and through research, he identified five communities that actively practice their craft and are also open to working with entrepreneurs. Presently, Niñofranco collaborates with 30 artisans, all women, across five communities: the Bagobo Tagabawa, Tboli, Blaan, Mandaya, and Tagakaulo.

Dismissing the title “designer,” Wilson instead uses the term “creative director.” According to him, he isn’t designing anything—the indigenous artisans are. His role is to reimagine the textiles they design and make; to put forward interpretations of it that they might appreciate.

It’s what he did for one of their bestselling scarves, a fusion of the Blaan’s Tabih Dafeng (tubular skirt) and Swat (beaded comb headdress), both traditionally worn by women. The patterned scarf was adorned with tassels that referenced the suspended string of beads on the Swat. “Super hit ng scarf na yun sa kanila. Sabi nila na they never thought that yung product nila, pwede din pala gawing scarf [That scarf was a hit with the community. They said that they never thought that their product could be made into a scarf].”

The creative director reveals that the weavers are free to replicate the scarf and sell them independently, as it is “technically theirs.” His only request is that their items come in a different color from what’s being sold under the Niñofranco label. “I mean, that’s the point. Kaya ako nandyan [That’s why I’m there]. It’s to help them sustain their livelihood.”

Gestures like these are what keep his relationship with the artisans strong. Currently, the brand is focused more on embroidery and beading on linen and cotton fabric, but Wilson still makes time to visit the indigenous groups at least five times a year, and sets aside a part of the brand’s profits to provide them with school supplies and basic needs. For Niñofranco’s first trunk show, he insisted that one representative from each community walk on stage after the presentation. “They were so happy,” Wilson remembers fondly. “I think that’s how you empower them. You give them a place to be seen.”

Words & Styling by TICIA ALMAZAN Photographs by JOSEPH BERMUDEZ. Makeup & Hair: Goldie Siglos. Model: Ivanna Lagman. Photographer’s Assistants: Adi De Gracia, Ellah Plariza. Stylist’s Assistant: Patricia Villoria. Shot on location at Dusit Thani Lubi Plantation Resort.