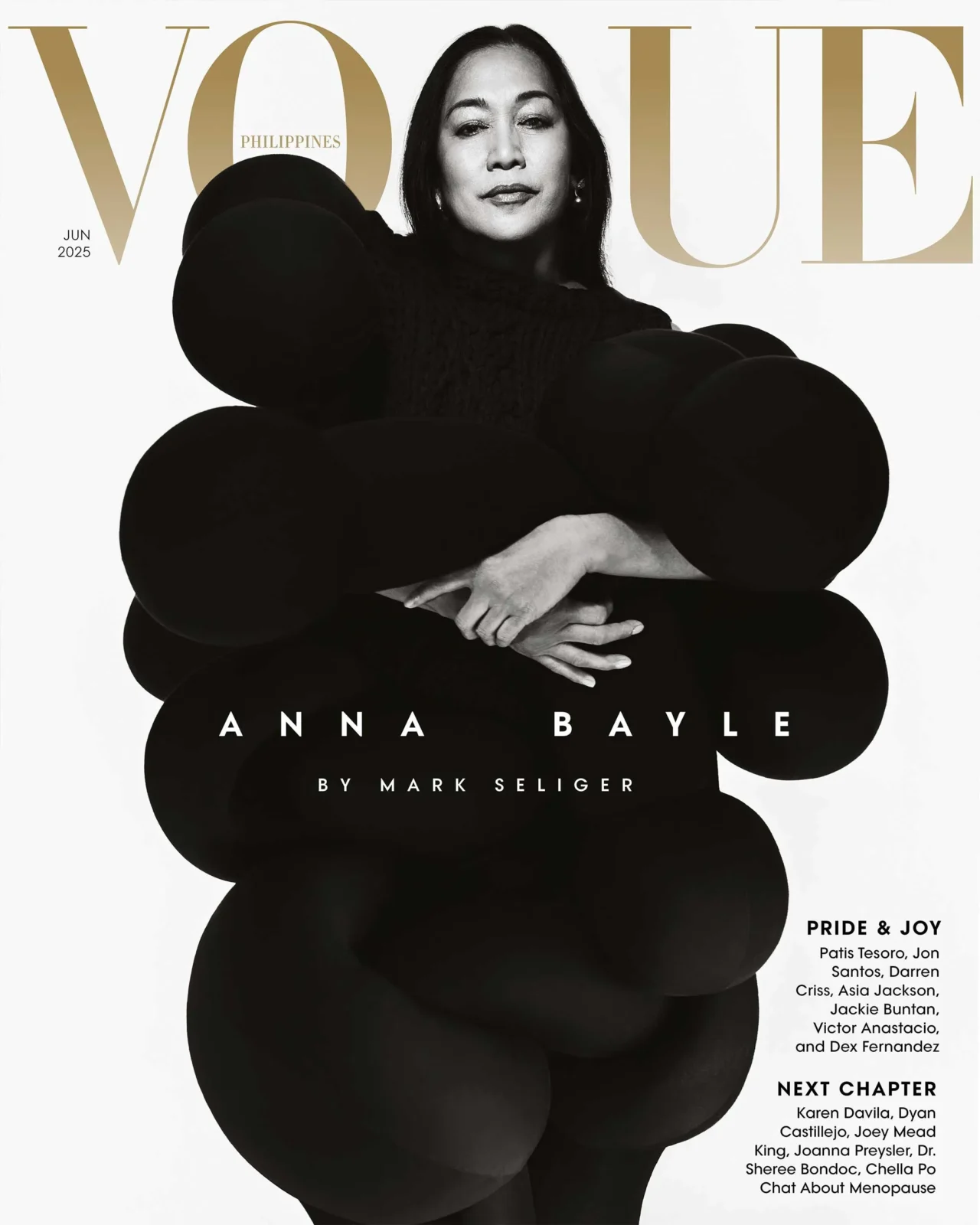

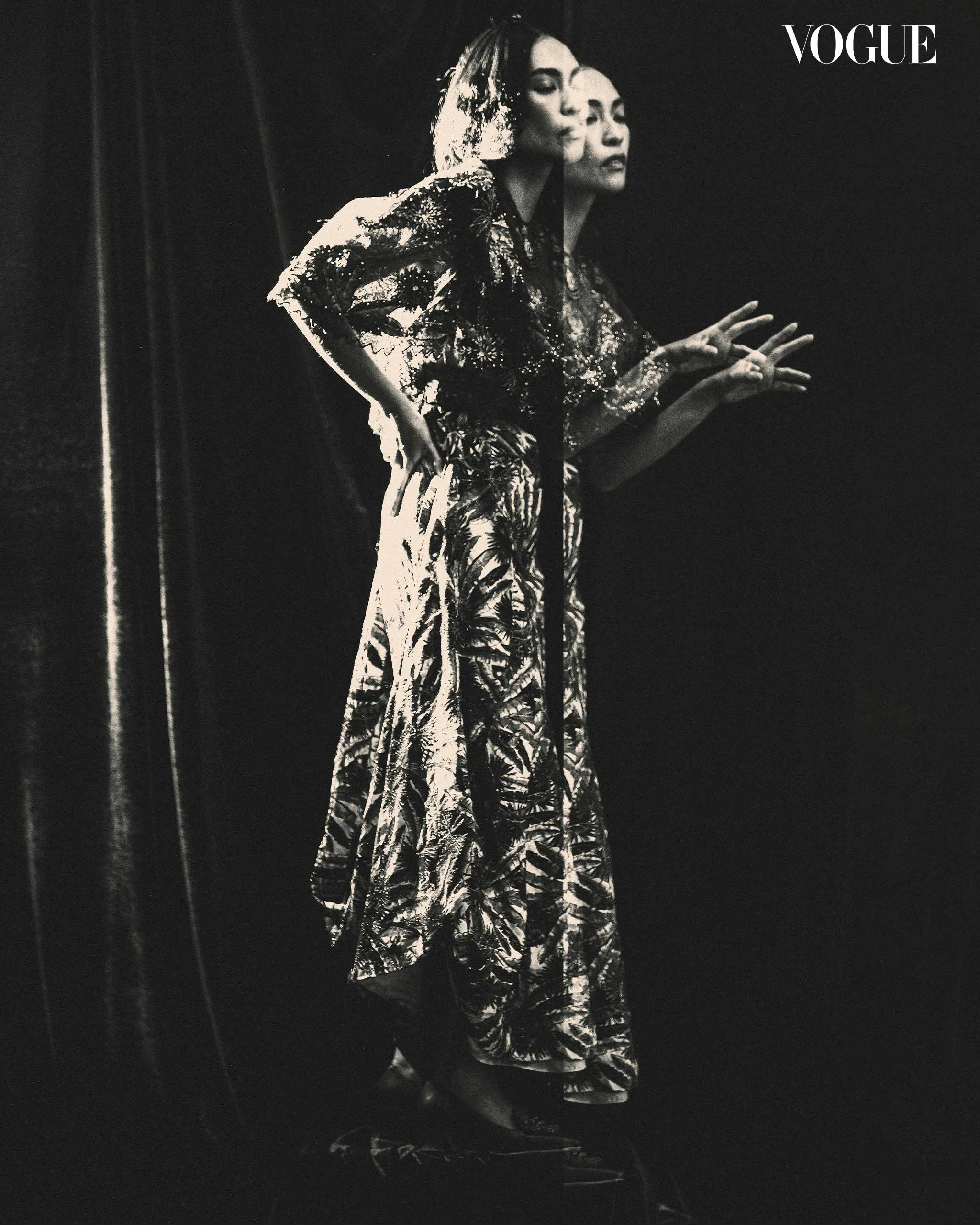

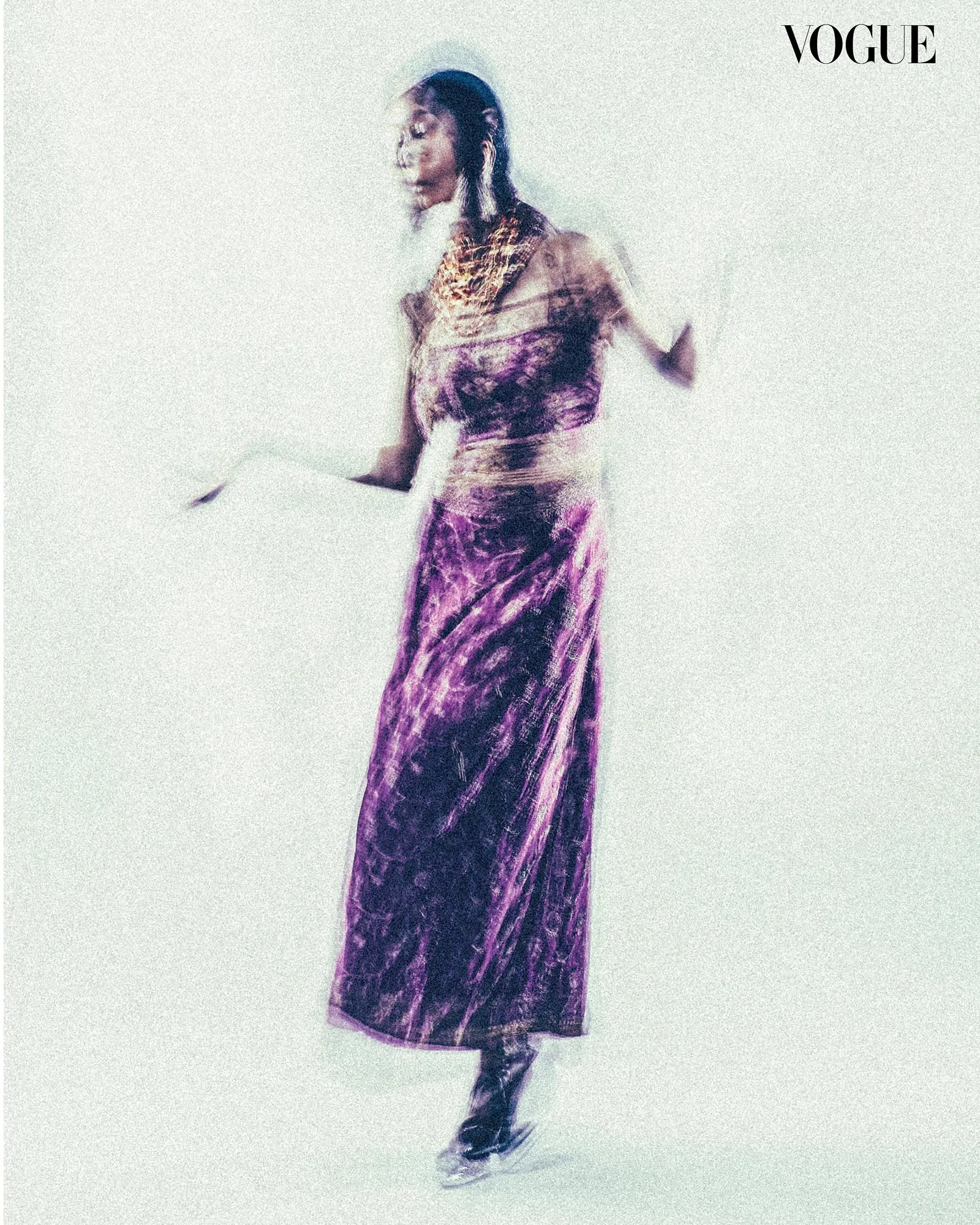

In 1989, Evelyn Lim-Forbes commissioned Tesoro for a look that could be worn for different occasions. The designer decided on a “tropical, lightweight design that would not age,” Lim-Forbes recalls. “I have worn this outfit many times and have always felt like an Amorsolo figure when donning it; not bad for a 35-year-old dress.” It is worn here with UNANG PANAHON jewelry. Photographed by BIMPOMAN for the June 2025 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Patis Tesoro’s design philosophy isn’t limited to her pieces; it is lived, woven into the fabric of her waking world.

Time moved differently in San Pablo. It did, at least, within Patis Tesoro’s home studio, where its residents, guests, and staff took their schedules very seriously. The pulse was in stark contrast to its surroundings, which invited a slowness, paced to the dance of dappled light cast by ventanillas, the rush of a breeze between looming branches, the infrequent birdsong.

Still, everything had to run on time; the kitchen and atelier would close at 5 P.M., no exceptions. Here, someone would constantly remind you of the time, kept in meals, made-to-order pieces, or, in today’s case, a 15-piece collection due at 2:45.

The sky was overcast when Vogue arrived just a bit after noon; thankfully on schedule, as we’d later learn, for a brief encounter with the veteran Filipiniana designer and textile artist. It took a few drive-bys to find the complex, which sat on a long, narrow street, behind a gate weathered by rust and half-hidden behind overgrown plants by the wayside.

Off the gravel driveway, we enter on a mossy stone path that slowly reveals, between large leaves and overhanging vines, a carved wooden sign that reads “Patis” above an entryway. This two-storey building, the Verbena, is the first stop on our informal tour. Inside, every corner was a riot of pattern, texture, and color. Murals trailed the length of the walls through to the ceiling, depicting budding blossoms and verdant leaves, swirling over a swell of golden clouds.

At the room’s center, racks made from bamboo are held upright by clay pots filled with earth. These are populated with Tesoro’s more recent ready-to-wear pieces: a mix of printed caftans, day dresses and beaded gowns, barongs embroidered with tropical scenes. Along the sides of the room, the bamboo rods are lined with rolls of fabric that sing. The variations of abaca, piña, and calado, which were dyed or hand-painted or embellished with glass beads that glimmered in the light, looked more like a display of the breadth of local creativity than regular boutique offerings.

Individual tags were pinned to each piece of yardage, with neatly handwritten descriptions detailing its technique, colors, and what kind of Filipiniana it could be used for. “Handwoven Piña Suksuk / Green/Orange Suksuk / Barong,” one of them read. Another, “handwoven piña calado / dyed black.”

A low hum of soft chatter and sewing machines whirs from the adjacent room on the left, where artisans and artists work on made-to-order pieces, and more urgently, the collection Tesoro would present the next day, during the unveiling of her documentary and four-kilo book spanning five decades of work, both titled Filipiniana Is Forever.

Tesoro themed this collection to her current sentiments that leaned more “bohemian.” These Filipiniana profiles were freer, looser, but still held the vibrancy of her signatures in embroidery and embellishment. Her workroom staff was due to present the final pieces for her review later today.

It wasn’t long before we were told Tesoro was ready to receive us at the main residence, which was across the garden in the center of the complex. Down the walkway and around a bend, we meet double doors with brass geckos for handles. We find Tesoro immediately upon entering, sitting at her breakfast table and dressed in a primarily pink printed daster with lipstick to match. She greets us with a bright smile. We’re here for our video interview, we tell her, and ask if she’d like a quick touch-up. “Oh, makeup?” she fans. “You don’t have to worry about that.”

Lunch is served right as we finish our introductions, and Tesoro leads us inside to present the dishes on today’s menu: a large serving of white rice, ginisang gulay [sauteed vegetables], red egg salad, and beef rendang. She cooked the latter herself, she tells us, “Though I don’t eat meat anymore.”

When Tesoro sees her guests’ meals piled onto their plates, she sits at the kabisera, and then starts at the beginning.

“From the age of six years old, we really knew how to embellish,” she narrates, speaking of her time at Assumption Iloilo, where nuns taught her and her classmates how to make placemats, tablecloths, and bedsheets, skills for a housewife. Tesoro describes this time in her life as when she discovered her innate affinity for embroidery and embellishment. “My hands were small, but it was something I liked to do, while my companions, some of them, did not like it,” she told her daughter Nina Tesoro-Poblador in the introduction to Filipiniana Is Forever. “It wasn’t like that for me. I was always interested in it.”

That interest would amount to actionable pursuit, when Tesoro began selling her handmade pieces in a small, quiet section of her mother-in-law’s shop, Tesoro’s: The House of Philippine Treasures. By the time she was 19, she was formally in the business of ready-to-wear. Her first inspirations were romance novels, the British designer Laura Ashley, who was known for her Victorian era-inflected floral dresses, and the Christopher Reeve and Jane Seymour starrer Somewhere In Time, which she frequently referenced in her designs.

As there weren’t many working models then, Tesoro’s maiden campaign cast her friends. They were photographed stepping out in boxy shift dresses in summery shades of cream and pale pink, machine-embroidered over with simple floral patterns and often belted low at the waist with strips of fabric that, on some pieces, had their ends twisted at the front to evoke a 3D bloom.

She was also experimenting in the Filipiniana as early as then, learning the nuances in structure and technique. In her early designs, her embroidery elements were “basic but always prominent,” reads one caption in Filipiniana Is Forever, as seen on lace appliqués applied on sheer butterfly sleeves and colorful suksuk designs on barongs.

“I think in art, we are inspired. It must go on to the next, and the next, and the next generation.”

At the time, Tesoro frequented salons organized by the Patrones de Casa Manila, an informal group of friends bonded by their love of 19th to 20th-century Philippine history and culture. They gathered together to reenact scenes of the past, which mostly meant that “we would just sort of like sit there,” Tesoro told Nina. “But the mere experience opens up your mind all the time.”

In these tableaus the Patrones would wear traditional dress: barongs, maria claras, or baro’t sayas in colonial-era styles. By her association with the community, Tesoro would end up receiving more orders for Filipiniana.

But she soon noticed that the piña she used to create these pieces was becoming increasingly scarce. “In my thirties, I saw that it was dying,” she starts. “I had to work with the Department of Agriculture.” Well, it’s not like she had to. (“Jusko, ‘day!” she cries, just at the thought of it. “No one wants to go through the pain of revival.”) But to her, stasis was not an option. “Because if you don’t have the source, you cannot do anything,” she says. And do, in her case, meant create.

Tesoro set out to revive piña weaving in 1986 by making countless trips to Aklan, at the time the only source of piña in the country. There, she met with generations of weavers to learn about their process from harvest to weave, and with local officials to lobby for weaving programs for the youth. After a successful campaign in the province, she moved on to Lumban, then to Abra, this time in pursuit of reviving their natural dyes. Soon she would travel the country over, and wherever she went, she found histories to resurface.

To date, the designer is not only credited with the revival of piña but also of various cottage industries across the country: natural dyes and textile weaving in Ifugao, Mandaya fiber, bag and hat making in Lucban, weaving abaca and pineapple fibers with silk threads in Kalibo, machine embroidery and weaving in Bulacan, Tboli abaca, and jusi (handwoven Philippine silk) and patadyong weaving in Iloilo, to name a few.

With enough material to source, Tesoro found she could finally expand on her specific vocabulary, which comprised consonant and contrasting hues and typically opposing sartorial flourishes, tacking print on print on print, or pairing shades like red and green without it looking like Christmas. “My mom was a color connoisseur,” Nina tells me in a separate interview. “That was her superpower.”

However, her son Raffy Tesoro adds, she also had the capacity to create something very minimal. He cites one black velvet terno she made, still featuring embroidery and embellishment, but only kept to its white ruffled trim. “Everything else was completely black velvet,” Raffy recalls. “That was a complete 180 from her usual design philosophy, which is ‘I’m going to throw color and everything on it, and let’s see what sticks.’”

In practice, her pieces always tread the line between too much and not enough, pushing to extremes then paring back in quiet gestures. She would ground frenetic floral appliqué with thick lace trims, or she would veil full-saturation prints beneath sheer half-slips (or anaguas, traditionally worn as inner garments) to act as a kind of soft filter.

As a purveyor of local craft, Tesoro’s references to our heritage textiles and techniques were wide-ranging, from subtle to more overt expressions. One Victorian-era reminiscent gown used a hand-loomed, mixed tribal fabric hailing from the Cordillera, accented with embroidered lace from Bulacan. She used patadyong, which hails from the Visayan region and is historically worn as a tube-like skirt wrapped around the waist, for Antipolo-style ternos and Western-style dresses. For another terno, she sourced inaul from Maguindanao and tailored it into a form-fitting bodice that flowed down to a trumpet-cut skirt; in this light, the textile evoked the feeling of a rich brocade.

In the sum of a body of work spanning five decades, a Patis Tesoro label piece was never left without the thing that could define it as distinctly Filipino. Often, that meant embroidery and embellishment techniques, honed through generations, and in some parts of the country, under her guidance, through continuous, uninhibited experimentation. “Embroidery can encompass beading or flower-making,” she explains further. “Basta (as long as) we embellish.”

Nina and Raffy say that what best defines her signature might be her ability to produce this uniquely Filipino sensibility. Creativity is a means of communication, Raffy explains, and “she is an excellent cultural communicator for the Philippines. Why does it resonate? Because she is communicating Philippine culture to the Filipino.”

Throughout their years helping stage their mother’s runway shows and archiving her pieces, Nina and Raffy were quick to witness when identical work would dot the market, expressing that if anything had to change within the Philippine fashion landscape, it was artistic integrity. While there is value in their sentiments, Tesoro holds opposing views. “I do not mind being copied,” she says simply, unprompted. “I think in art, we are inspired. It [Filipiniana] must go on to the next, and the next, and the next generation.” She pauses for a moment. “Because I am at the exit of my life. We are Filipinos. We must continue the legacy.”

Craft as ritual

“I always like to create, so I’m continuously creating,” Tesoro tells us at one point. “When you do art, for me and for most artists, it’s not for the money. It’s for your own well-being.” She confesses that she still keeps to her rituals, which begin as the sun rises, with her drawing at her desk. Her morning meditations come in the form of wild blooms or swirling vines over pebbled backgrounds, or psychedelic, petal-pumped spirals that, upon closer inspection, are made up of tiny and tinier curved lines.

She says that they come to her as visions in dreams. Although I suspect, drawing connections between the budding blossoms in her garden to the abstractions in her boutique, that art is how she’s come to continually make sense of her world. The Laguna home she’s built reflects the design language she’s known for. Ventanillas capture the feeling of callado and embroidered drawnwork, and Machuca tiles and glistening mosaics embedded in the pavement her colorful beadwork.

“All of that is really what she stands for,” Nina says. “Her value system includes creativity, greatly, but also the sustainable Filipiniana lifestyle that she lives; the fact that this Filipiniana lifestyle includes planting what you eat, includes cooking the food you’ve harvested, includes making the clothes that you wear, and includes creating from a very basic level.”

When Tesoro isn’t working, she’s in her garden tending to plants, flowers, and vegetables that make it into her daily menu. Other times, she’s caring for her 28-and-counting dogs that she knows by name (on either side of her now, at her dining table, are Boom and Sh-Boom, black and white Shih Tzus named after the ’50s Chords single). That, or she’s passing on what she knows, in this space that kindles a creative spirit the same way an artist residency does.

We learn that the murals at the Verbena were painted by Madonna, the son of one of Tesoro’s embroiderers, who grew up to be her executive assistant, regularly receiving clients and visitors and managing stock. In her atelier, one of the painters was formerly a guard on the grounds. “I teach,” Tesoro says. “Basta they have talent, I teach.”

At the moment, she has no plans of retiring, although the thought does come and go quite often. “I’m already 74. I watch K-drama, you know, I’m like, I don’t want to do this anymore,” she smiles, only half-joking. “But I’m willing to do it.”

Promptly at 2:45 P.M., her seamstresses carry in bamboo racks with the pieces for her collection due to present tomorrow, which comprises sheer printed caftans, embroidered piña baros, and malongs that she says are meant to be styled the way our ancestors wore them: without a regard for whether they matched or not.

In a lot of ways, this is the throughline of her more recent design fixation, Bohemia Filipiniana. Relaxed profiles, kimonas and tubular skirts, feature an eclectic mix of embroidery, embellishment, and hand-painted motifs that could have only been puzzle-pieced together through her skilled eye for curation. The patadyong is reimagined with patch-worked prints and beaded flowers.

This type of casual daywear, along with her other new pieces (that are mostly custom not by choice but because “they sell out before they make it into a collection”), is filed under the chapter in her design career she’d like to assign the same title as her full body of work, Filipiniana Is Forever.

If her early work consisted of the experimentation and revival of local craft, her designs today are a celebration of it. There are styles inspired by her travels across Asia, iterations of traditional Indian and Chinese silhouettes that have embedded themselves in her mind. Her versions depict Filipino artisanal craft against kinds of blues, indigos, mossy greens, and searing reds.

Poignant, lucid expressions are strewn across the baro’t saya, traje de mestiza, maria clara, and terno. Tesoro uses gold thread in fine strokes, swirling over gossamer-thin piña veils, beads either sparingly or from butterfly sleeves through to the hem, and tailors to precise lines that move with the body.

The expansive medley isn’t a rewrite of the Filipiniana’s foundations, but the assurance that what we know can be made new. “Clothes not only define a person but also a nation’s identity. We must look back to our colonial past, when we fought to wear our own despite the availability of foreign alternatives,” she says in her book. Does she think the Filipiniana will truly endure? “I think so, if we make a conscious effort to wear it.”

Still sitting at her dining table finishing her dessert, Tesoro gives feedback for her collection’s finishing touches with an eager swiftness that gave away her intentions: she will keep creating, as long as the world continues giving her ideas.

She left in a flurry that afternoon, running late for a dialysis appointment. The pushback in her schedule never changed her demeanor; she was as giving as she had been when we met.

That evening, we checked in at the second floor of the Verbena, which functions as a lodge for Tesoro’s guests. The walls weren’t left untouched by Madonna’s murals. This room featured pothos, philodendron, and carnations in ceramic pots and vases of varying sizes.

As darkness fell on this corner of San Pablo, the Verbena’s lamps glowed neon pink and blue. Their residual light cut through the pitch-black, casting new shades on the paint strokes on the walls. Any lodger would find, after a day spent in time with the workings of Tesoro’s world, that rest came easy, and nights here could be just as vivid as the day.

By CHELSEA SARABIA. Photographs by BIMPOMAN. Fashion Editor DAVID MILAN. Deputy Editor: Pam Quiñones. Media Channels Editor: Anz Hizon. Producer: Bianca Zaragoza. Makeup: Zidjian Paul Floro. Hair: Gab Villegas. Model: Merille Madaus-Bruck. Nails: Extraordinail. Photo Assistants: E.S.L. Chen, Ruzzian Escaros, Sam Stax.