The Christian Dior pre-fall 2023 show took place in Mumbai on March 31, 2023. Photo: ©Dolly Haorambam / Courtesy of Christian Dior

The Christian Dior pre-fall 2023 show took place in Mumbai on March 31, 2023. Photo: ©Dolly Haorambam / Courtesy of Christian Dior

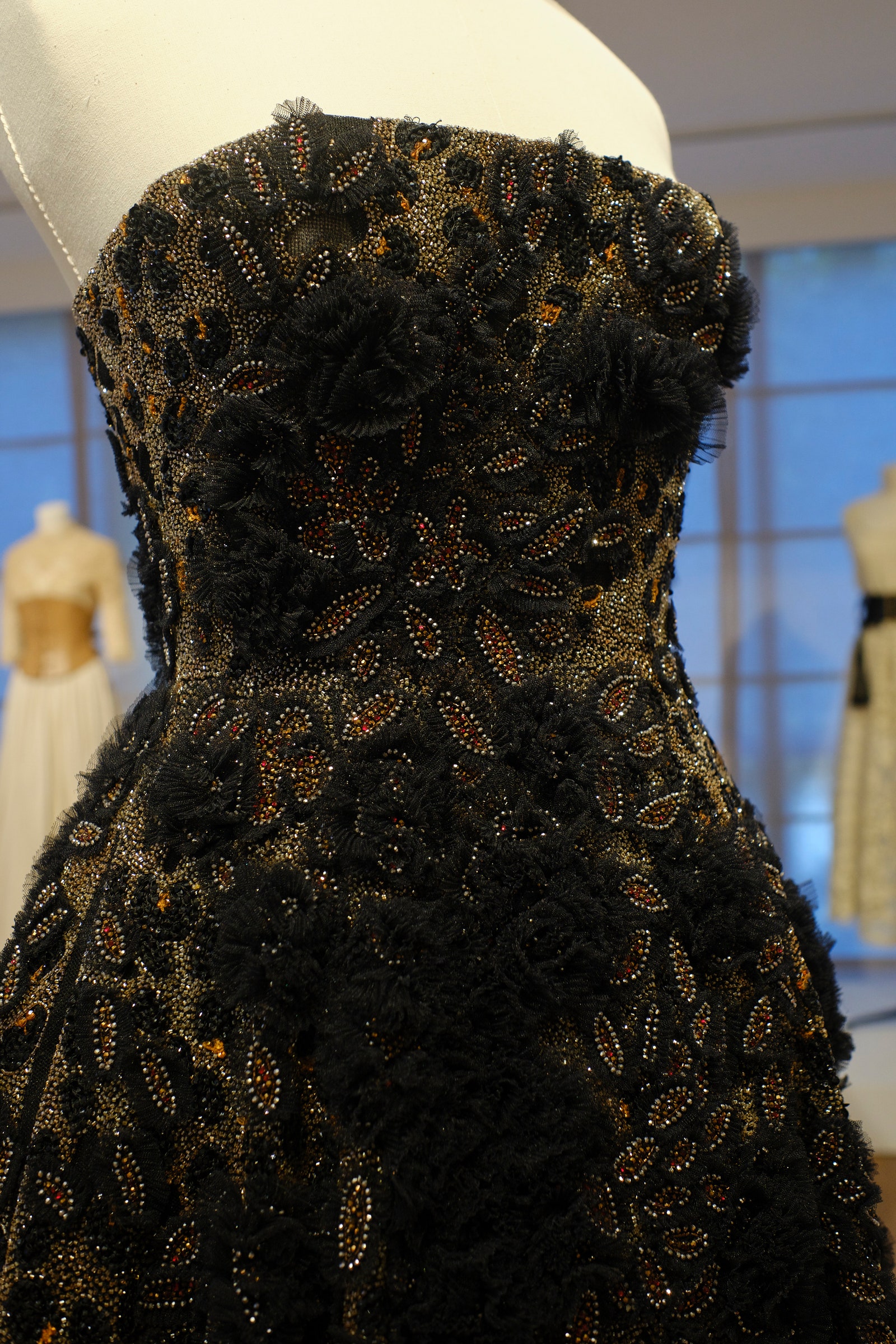

There was something quite mind-blowing about the whole experience of being present at Maria Grazia Chuiri’s introduction to India—or rather, to her making visible all of the many ways that Christian Dior is interlinked with the artisanship centered in Mumbai. One moment, you were taking in the epic scale of a show on the harbor, silhouetted against the Gateway of India landmark, with a runway flanked by a carpet of multicolored flowers. And the next, your retinas were being irradiated by the microscopic ingenuity of Indian traditional handcrafts sparkling—all-over mirrored Rajasthani embroidered mini-dresses were part of it—under a revelatory spotlight.

Earlier in the day, the creative director of Christian Dior womenswear sat chatting with Karishma Swali, the artistic director of Chanakya Ateliers, where all of the intricacies of the insanely detailed haute couture textiles are magicked up for the Paris maison. The two have a deep-rooted professional friendship that’s been going on “for almost 30 years,” laughed Chiuri. They first got to know each other as far back as 1992, when Chiuri began traveling to Mumbai to work on embroideries with Chanakya when she was designing accessories at Fendi. Together, since Chiuri began at Christian Dior, she and Swali have pushed both for the visibly spectacular and the feminist and ethical—on the one hand, the production of the vast textile murals commissioned from women artists that decorate the walls of Dior couture shows in Paris, and on the other, the establishment in 2015 of the Chanakya Foundation school which educates women in crafts and opportunities in a largely male-dominated field.

“From the very beginning, apart from being a symbol of grace and elegance, Maria Grazia has also been someone who’s extremely generous. I think our values kind of radiate outwards,” said Swali. “She’s someone who’s incredibly inspirational for us. Then she pointed out an embroidery that she and her teams had dreamed up to symbolize the woman they know Chiuri to be: “We created this double-headed pop-lioness that I think perfectly encapsulates what we feel about her,” she said. “Because she has one ear to the past, and one eye to the future.”

Chiuri nodded, beaming, “because I believe that it is important to study the past very well, but at the same time to try to use these references in a different way, and also to renovate them. That is what I have tried to do when I look into the archive of Christian Dior. You cannot reproduce the past.”

She’s been talking for ages about what she’s been doing with Chanakya to journalists backstage at her shows in Paris. It was quite another thing to demonstrate the reality in person—with a group visit to the Chanakya Ateliers, and a chance to dive into the close-up wonders of the vast breadth of specialisms that have been passed down through centuries in India. Astonishingly, they number up to 300 distinct crafts. From Kantha, to Zardozi, to Pachisi, to Madras weaving and block-printing—it’s mind-bending to a novice viewer. “India is a continent. Each part is like a state, with its own traditional techniques and cultures. But I think, in the end, the connection to elements of nature is very strong everywhere,” Chiuri said.

Even to drive through Mumbai to the Chanakya Ateliers is to be visually overwhelmed by the city’s burgeoning nature: the lush green foliage, the tiny flowers and manicured miniature topiary, the banyan trees lining streets, the overhanging cascades of bougainvillea. The rhythm of pattern and color bursts out from everything, including black and white striped curbs, murals painted on concrete flyovers, and ramshackle corrugated fences. In Mumbai, a talent for decoration, for the possibility of making things, and changing whatever little one has for the better are collective qualities that have been long-forgotten in parts of the West.

Inside Chanakya’s modern-built complex, Swali had laid on an exhibition of the antique textiles she’s collected from all over India and beyond; pieces which stimulate the kind of cross-cultural research that ends up—differently every time—in Dior collections. It was a chance perceive from two inches away that the 3-D beige roses on a filigree dress are actually made from crocheted raffia, or that the glinting lace of another is achieved through ancient Mughal-era zari silver and gold thread embroidery.

Downstairs, craftspeople were working at benches and looms, or sitting working on the floor collectively. In one zone, you saw how the reference of the tree of life, embroidered on an antique bed-covering, was echoed through the floral edging on a pair of 17th-century French silk waistcoats, and how an artisan was now satin-stitching garlands of miniature flowers on the makings of a Dior dress. Guides talked through each skill, and its roots in regional and tribal cultures. “We have artisans that are experts in everything. It’s a lot of hours, a lot of work, a lot of really technical stuff. These are artisans that can be 13th generation—in the sense that they’ve been passing down this craft for so many years. Now they’re the experts with regards to needle-making, with regards to lace work, to crochet, thread-work, fine-stitch sequencing,” one said, proudly concluding, “so there’s no chance of them getting it wrong.”

Chanakya has these different artisans from around the country, a workforce of 300 to 400, mostly men, whose skills have produced the vast tapestries that Chiuri began commissioning with the artist Judy Chicago’s installation for spring 2020. That’s an impressive achievement, yet even more so is the non-profit school that Swali has established and which is supported by Chiuri and Dior.

That department, on another floor, was open for visitors. Swali’s staff explained how they’ve trained 1,000 women, the youngest aged 16, the eldest 60, in the eight years since it was founded in 2015. The program is structured over 950 class hours, which can be taken as the students can manage time-wise, so they’re “building craft excellence in their own time.” To help overcome financial barriers, travel is paid for. After a year, the graduates may be offered internships. Many others, though, have set up their own businesses on leaving, or started to teach. “We encourage entrepreneurship to leverage any skills learned in our curriculum.”

Paying it forward for the independence of India’s diverse communities of women and girls is clearly one of the greatest satisfactions for Chiuri and Swali. Observing them, it’s obvious that it’s one of the bases of an eye-to-eye connection that’s gone much deeper than the typical transactional relationship of client and supplier. But they also simply share a common delight in the work—the magical textiles—that they can endlessly create that have never exactly existed before. “The idea is also to be able to mix techniques. It’s really teamwork,” Chiuri exclaimed, glancing at the friend and collaborator she knows so well. “It’s not even conscious for us,” she laughed. “It’s playing.”

Photographed by Sahil Behal