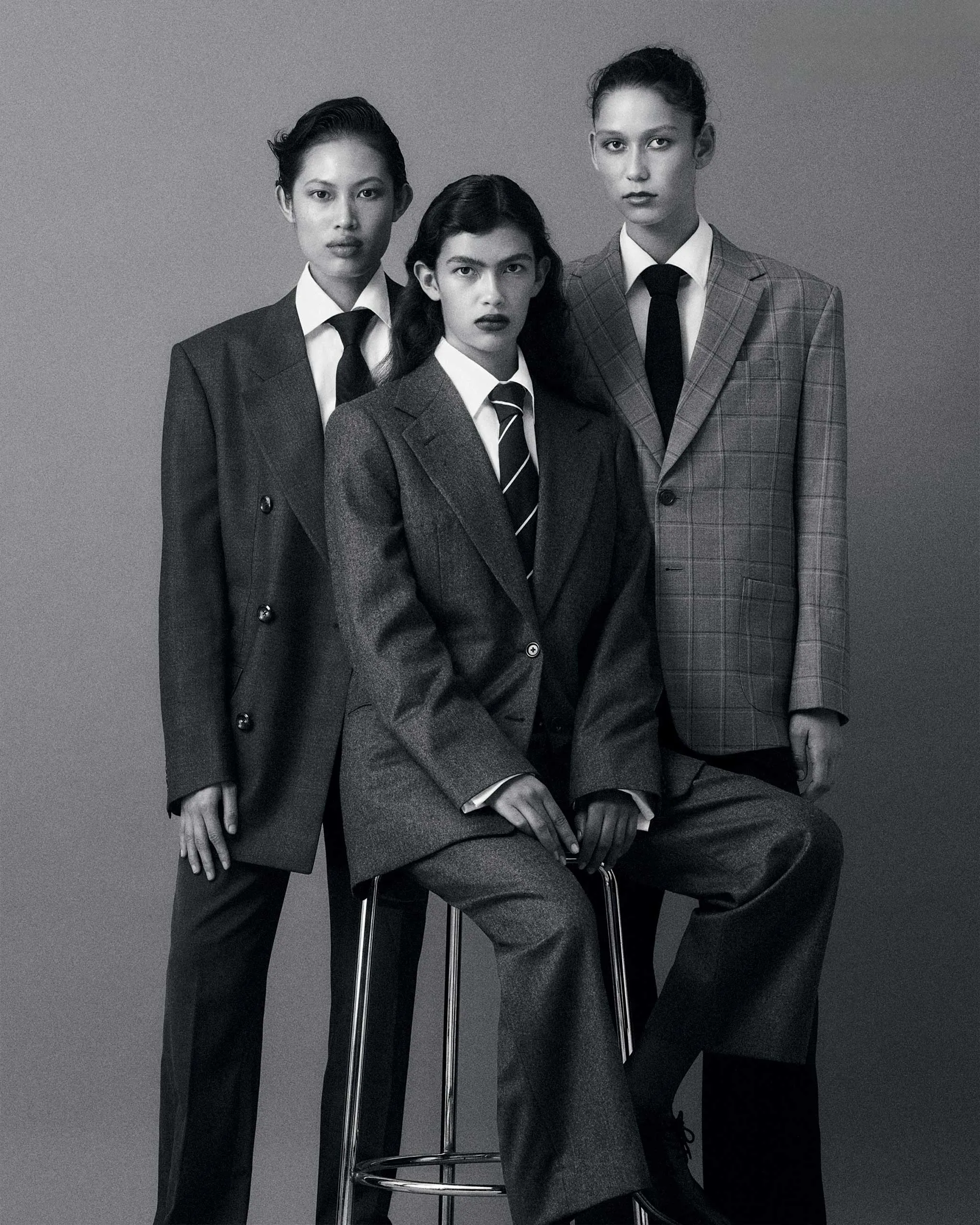

From left: Ploy wears an EMPORIO ARMANI men’s suit, shirt, and tie; Katie wears a P. JOHNSON suit, shirt, and tie, and BARED FOOTWEAR shoes; Selena wears a SUIT IT UP MANILA blazer, P. JOHNSON shirt and tie, and vintage YVES SAINT LAURENT trousers. Photographed by Diego Lorenzo Jose for the December 2025/January 2026 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Creative director Paulina Paige Ortega explores the suit and its visual history of self-fashioning as reclamation both here and abroad.

It was a childhood memory that Paulina Paige Ortega recalled often: the sight of her grandfather dressed for a formal occasion in freshly pressed, natty layers. It was the typical formula: a coat, trousers, and a tie. As sharp as he was, it was memorable, she says, because of the particular way he referred to himself: naka-amerikána. “I just thought it was really curious,” she furthers, “that Filipinos called suits, Western suits, amerikana.”

In itself, the term held an interesting tension; for Filipinos, to wear a suit was to interact with its history: in local context, as it has evolved under Spanish and American occupation, and further within a much larger, global conversation, on the attire as a symbol of poise or power or both, of fantasy and possibility, of assimilation versus self-expression.

In the Philippines, the suit arrived with the Americans at the turn of the century. It wasn’t the first time Filipinos wore Western clothing, as seen among the ilustrado and the upper class in the 19th century, but the “suit” by modern definitions was first seen on students and young men around 1910 to the 1920s. They wore a version that suited the weather; the amerikana cerrada featured black or white lightweight drill suits, with shirts that buttoned all the way up to standing collars, and was often accessorized with a Panama hat and a walking cane.

At the time, women still wore the baro’t saya, but even then, it began to transition in favor of Western-style clothing. Historian and academic Gerard Lico narrated these shifts in Siglo 20, a compendium of 20th-century Filipino style and design, writing, “The terno stripped down the pañuelo and tapis, and fused the camisa and saya into one piece, gradually changing the silhouette from the Maria Clara to the Gibson Girl.”

“It’s the same elements of wanting to transcend any hardship by just feeling good and confident…and you know, sometimes, that’s all a person has.”

However, the terno had longer staying power over men’s Barong Tagalog and camisas. Men frequently wore amerikana, as, before the country’s proclamation as an independent Republic, Filipino elite “tried to show they were equal to the West,” wrote Mina Roces in The Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas. By 1929, it was driven into popular culture, when writer Romualdo Ramos and cartoonist Tony Velasquez would debut the first serialized comic strip in the country within the pages of the prominent Tagalog weekly Liwayway. His titular character Kenkoy, despite his uniquely unserious, cheeky disposition, was always depicted as quite dapper.

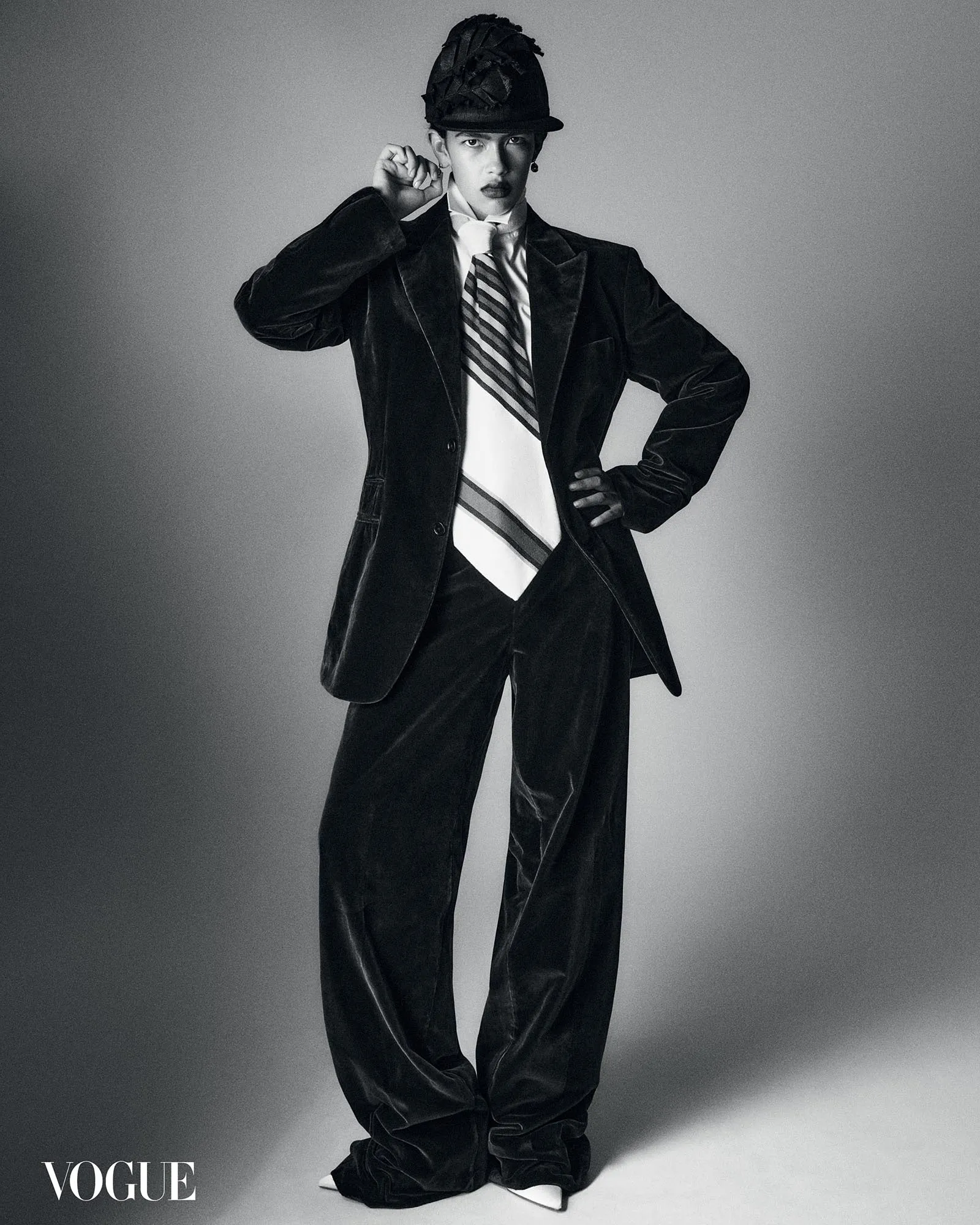

He wore a suit of slightly exaggerated proportions: a broad-shouldered coat with a cinched waist, an untucked collared shirt, and pegged trousers. On a few panels, his slicked back hair was topped with a fedora, and on others, he carried a walking cane. Intentionally or not, his appearance mirrored the look of the growing attitudes happening overseas at the same time in the mid-1930s, in America, on the far ends of each coast.

Just as Philippine menswear adopted the amerikana through colonization, Filipinos abroad had a hand in influencing the one suit that is considered to be “authentically American”: the zoot suit, characterized by its oversized coats with wide lapels, broad shoulders, and a cinched waist, and high-waisted trousers with pegged cuffs.

“No one really knows for sure where the suit came from,” begins Clarissa M. Esguerra, fashion historian and curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). “There are stories about a tailor from Pittsburgh, a tailor in Georgia, everywhere. One of the stories is that Filipinos came up with the style because they’re smaller.” She smiles, “I mean, who knows? That could just be somebody’s story, but that is one of them.”

The zoot suit would emerge as a trend in New York City, worn on the backs of the Black musicians, artists, and poets who made the Harlem Renaissance, and in Southern California, among Black and first-generation American men, particularly those of Mexican, Filipino, and Japanese descent. The people who wore them were “young, disenfranchised men who needed community and a way to express themselves where they felt proud and good,” Esguerra explains. “And so, they would adapt the suit to be seen.”

Their “drapes,” as they referred to them, were either bespoke or semi-custom to specification. At the time, Americans wore suits inspired by those from London and Milan, which were tighter and slimmer. By the 1930s, menswear had come to be characterized by the natural body, or a softer, draped silhouette that originated on Savile Row; the zoot suit was built upon that base, then “exploded” to exaggerated proportions.

In an opinion piece she wrote for Vestoj, Esguerra explains that the suit was a style that these men often had to work towards. “Although these semi-custom suits were more affordable than custom tailoring, the cost was still expensive for most working-class youths,” she writes. “The sheer extravagance in the draped shape of this suit suggests that it may have…[been] worn for performance, as the wearer would have generated such movement and presence in the pegged ensemble.”

“One of the stories is that Filipinos came up with the style because they’re smaller. I mean, who knows?”

The suggestion of performance was a defiant act. For many white Americans, the zoot suit was “a symbol of subversion, especially as racial tensions continued to rise,” at the height of Jim Crow. When wartime restrictions made the use of textiles in excess illegal, Esguerra tells Vogue Philippines, by wearing a zoot suit, “you were doing something that was ‘unpatriotic.’ But these kids, they’re like, ‘What do I need to be patriotic about, for this country that has done nothing for me?’”

Animosity was a price these young men paid, if only to look and feel their best. “The zoot suit came to symbolize a place that was theirs, that was for them,” Esguerra says. “It was a style that they developed. It was worn for a place they frequented and were welcome to be part of. It was worn as a celebration of themselves.”

Not only was the suit a display of cultural identity but also a means of dandyism, the philosophical idea that first emerged in 19th-century Europe, in which “taste” is favored over all other societal means of measuring a man’s worth. In American Black dandyism specifically, the gesture of customizing drapes to ultra-specificity was later streamlined into a language of superfine: jewel-toned color-blocked suit sets, bedazzled boutonniers, fantastically patterned shirts, and neat, crisp cuts that could only be tailored-for-you. That, or whatever fit, fabric, or embellishment it takes to be “well-suited.”

“Whatever makes a Black dandy today is what made a Black dandy of the zoot suit times,” Esguerra says. “It’s the same elements of wanting to transcend any hardship by just feeling good and confident…and you know, sometimes, that’s all a person has.”

While the zoot suit fell out of fashion by the mid-1940s, its narrative for people of color in America remains and continues to evolve by the decade. Black, Mexican, and Filipino American men, as well as Japanese Americans, Jews, and other minority groups, played a role in influencing the suit that would define men’s tailoring in America to this day, set apart from British and Italian suits by its looser, freer cut, and remembered as a symbol of found community and joy. As playwright Jeremy O’Harris recently opined in Vogue, “To be a Black dandy is to dress as though you know you’re loved and therefore have no use for shame. Shame comes from fear, and fear is the enemy of style.”

By 1946 in the Philippines, amerikana remained as the only accepted dress for men’s formalwear. But attitudes began to shift in the ’50s, as the country gained independence from the United States, and as politicians began adopting a public-facing affinity for the Barong Tagalog for special occasions to win over the masses and appeal to their desire for “simplicity,” as Roces writes. Ramon Magsaysay popularly chose piña and jusi over a coat and tie, and this “deliberately distinguished the new president from the elites with Western tastes.” And by the ’90s, the needle had shifted so that the Barong Tagalog had become both a standard for formal occasions and the popular choice among grooms on their wedding day.

As these shifts occurred, different movements were happening in womenswear in the West, more prevalently in Italy and America. Power dressing became normalized in the workplace, with archetypal big-shouldered coats often paired with skirts, and sometimes, trousers. A coveted Calvin Klein suit might be described as precisely tailored, with broad, straight shoulders, nipped-in waists, and long lines; this was the uniform of the empowered woman who worked outside of home and provided for herself.

To wear a suit today is to carry these separate histories, of identity, empowerment, and so much else at once. Revisiting that memory of her grandfather in what he called his amerikana, Paulina Paige Ortega engages with questions she’s had since she first learned the term. How do we reclaim or engage with the suit or amerikana as Filipinos?

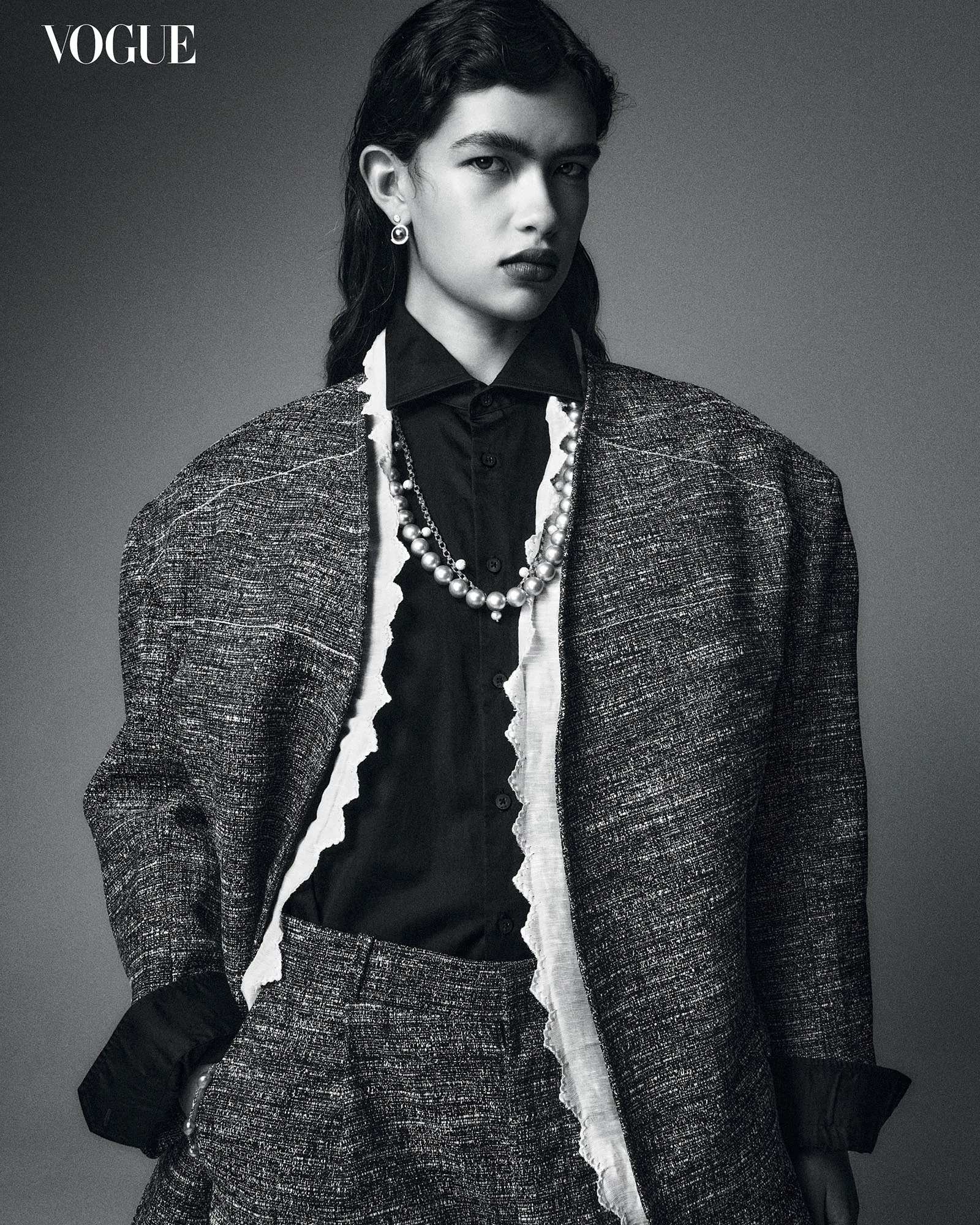

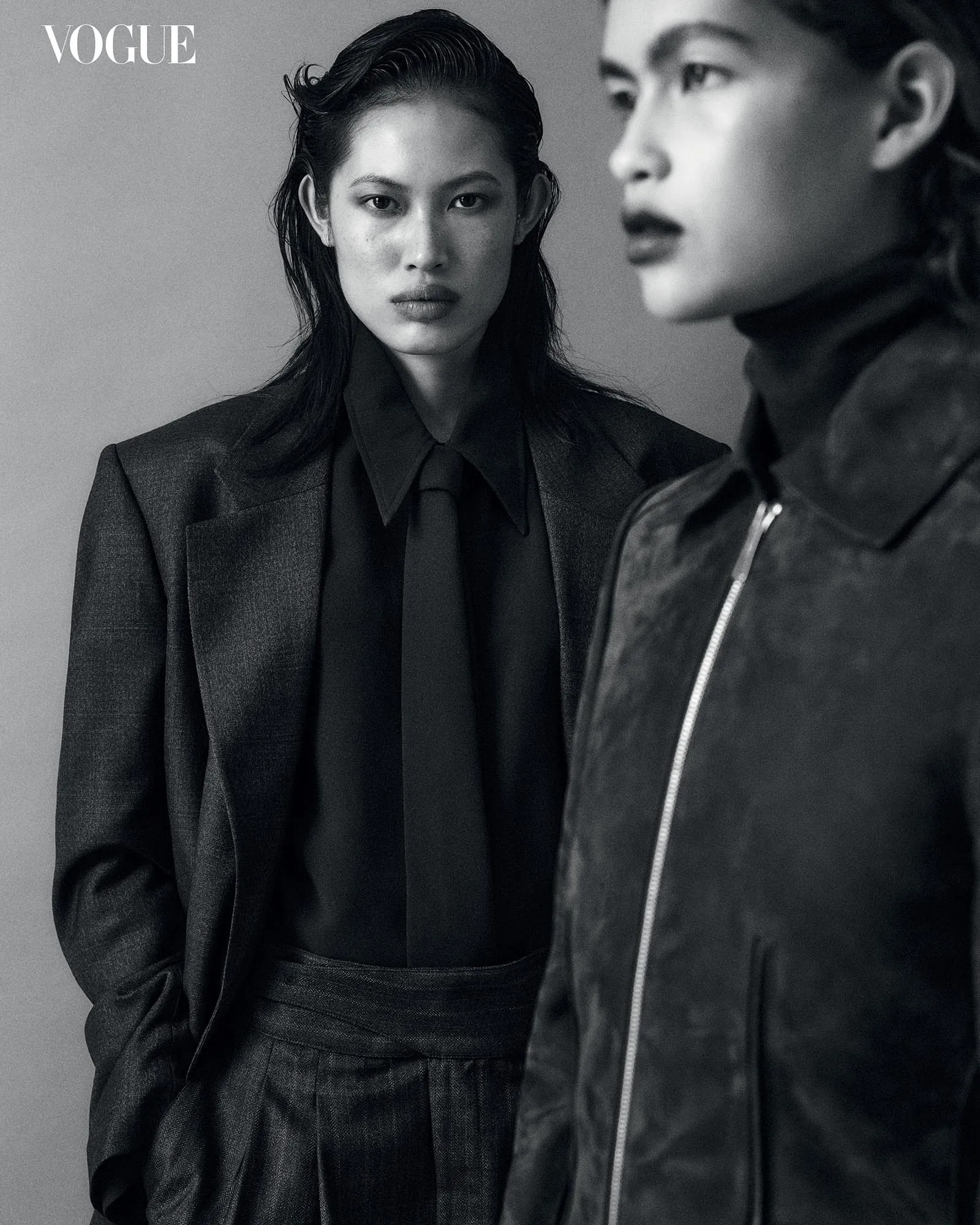

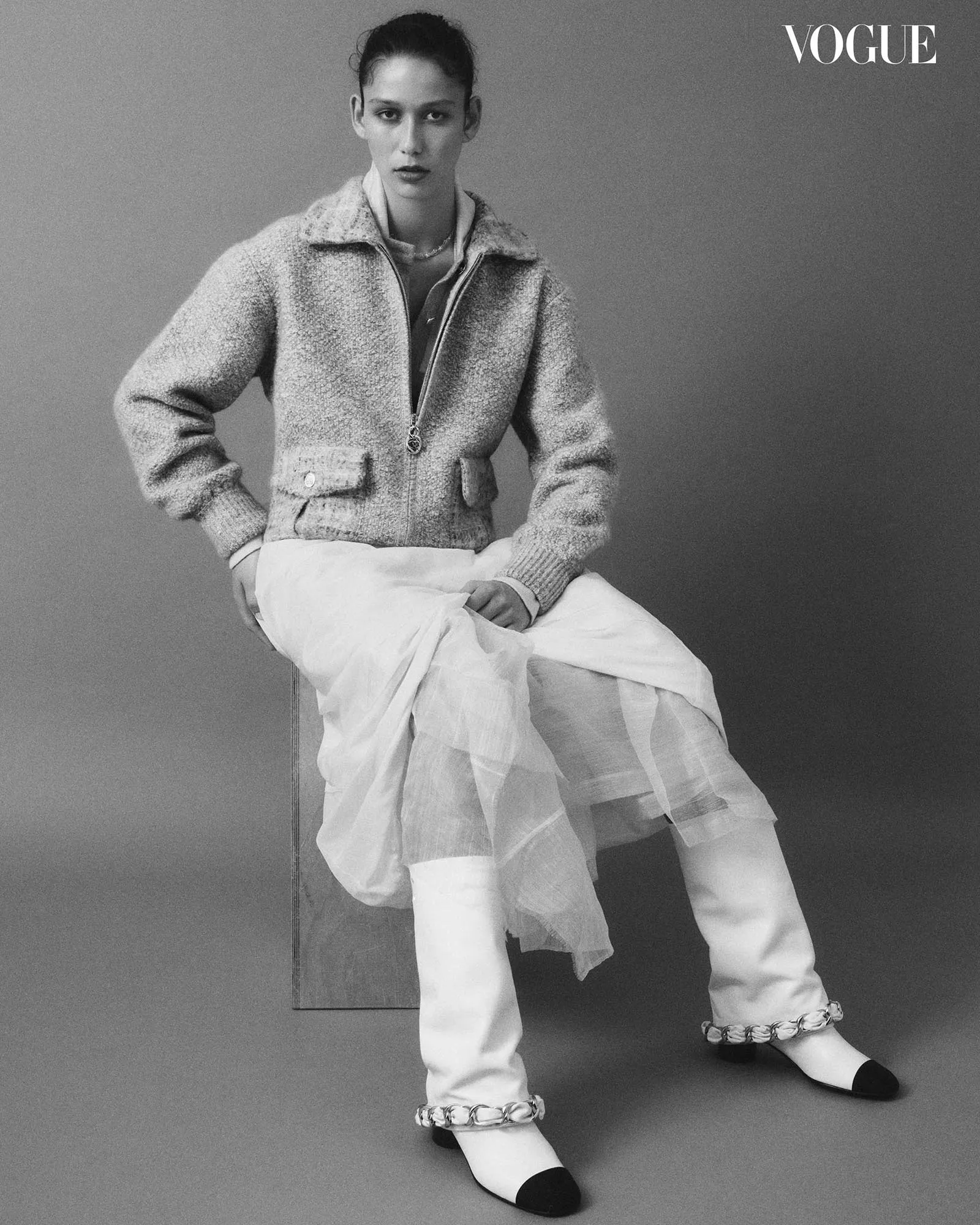

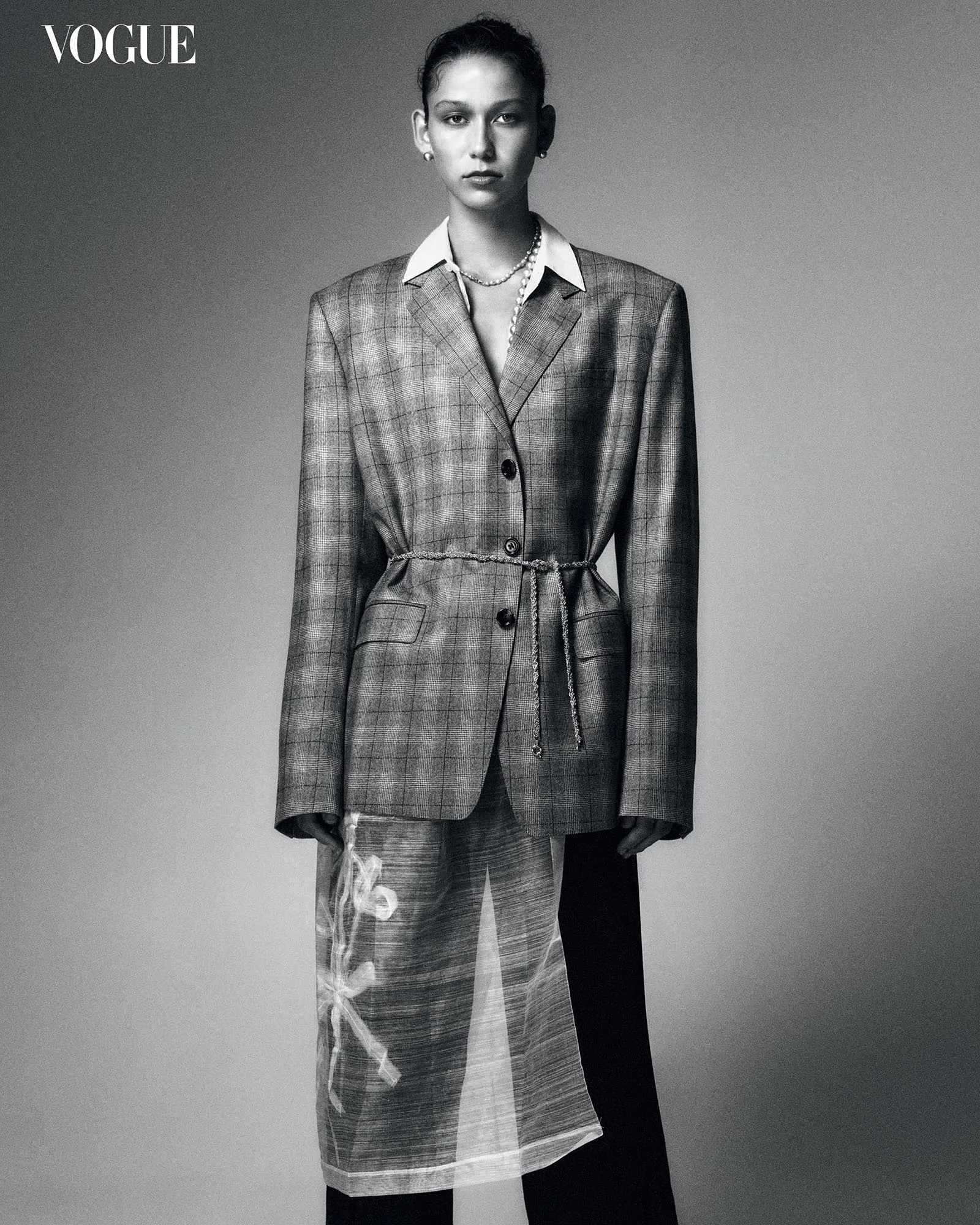

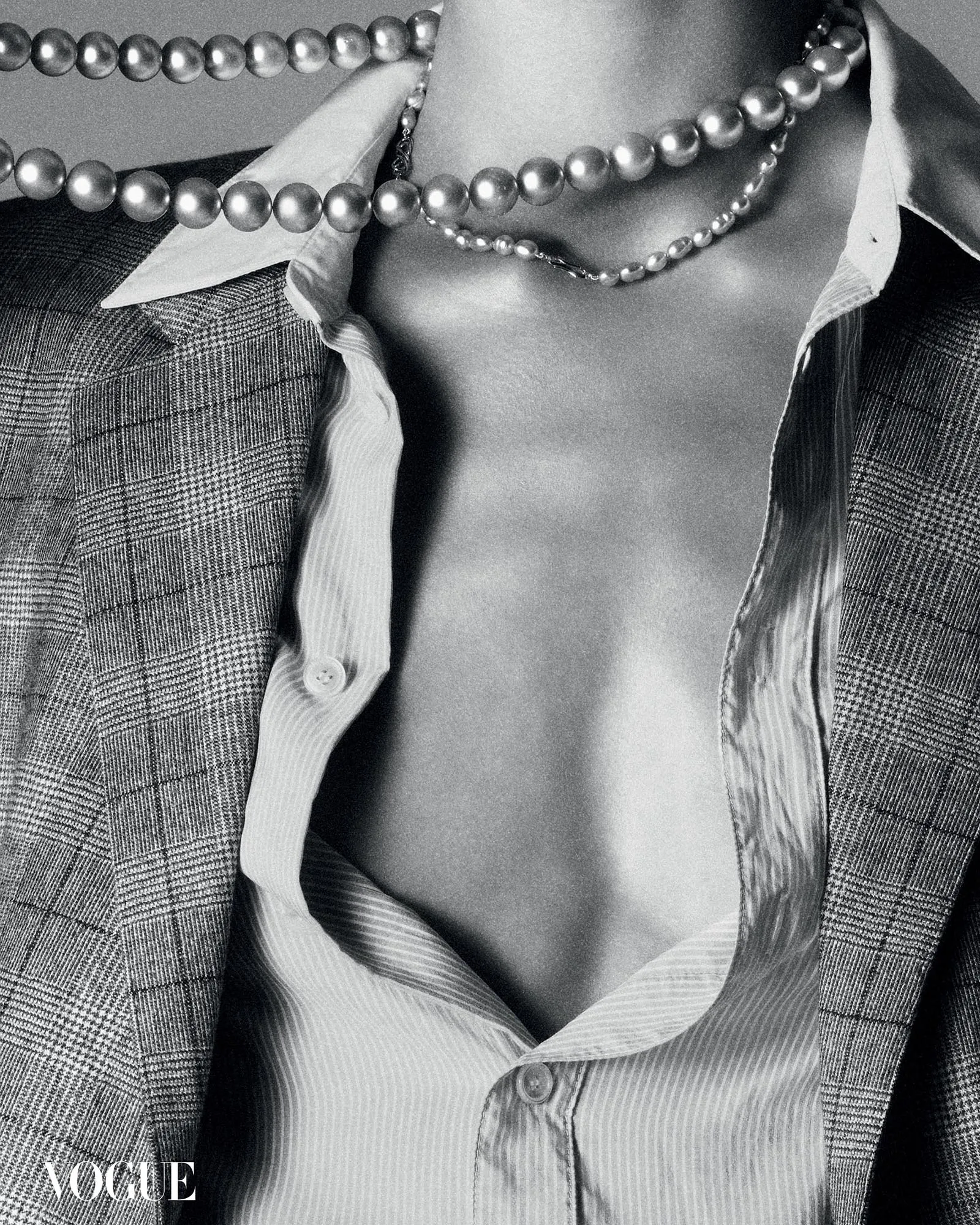

Photographed by Diego Lorenzo Jose and styled by Ilkin Kurt, Ortega’s interrogation into the topic unfolds over a mix of textures, blown-up proportions, and familiar silhouettes: in layered, sheer skirts that echo the tapis, the impression of a Maria Clara bell sleeve, and the raised collars that recall the time the amerikana cerrada arrived on our shores. She expands, “I really wanted to think about, as a Filipino in 2025, [the question of] how can I engage with suiting where I can bring other facets of my identity into it?”

“If anything,” Ortega clarifies, “this story is just a thought prompt, or the start of a conversation. I’m sure other people would have started it as well, but it’s something that we should continue having.” Wrought and wound with so much rich detail, the history of Filipinos’ perception of a suit, of the amerikana, is yet to be compiled; until then, new narratives will continue to be written. The needle still shifts.

“This conversation will evolve over time,” says Ortega. “As identity does.”

By CHELSEA SARABIA. Photographs by DIEGO LORENZO JOSE. Styling by ILKIN KURT. Creative Director: Paulina Paige Ortega. Lighting & Camera Assistant: Glen Edwards. Digital Operator: JP Westlake. Videographer: Duc Thinh Dong. Fashion Assistant: Genesis Mansilongan. Makeup: Victoria Baron. Hair: Rory Rice. Makeup Assistant: Celeste Gubb. Assistant Producer: Nicole Yagdulas. Models: Ploy Rida and Katie Crane of Priscillas, and Selena Feathers of FiveTwenty Model Management.