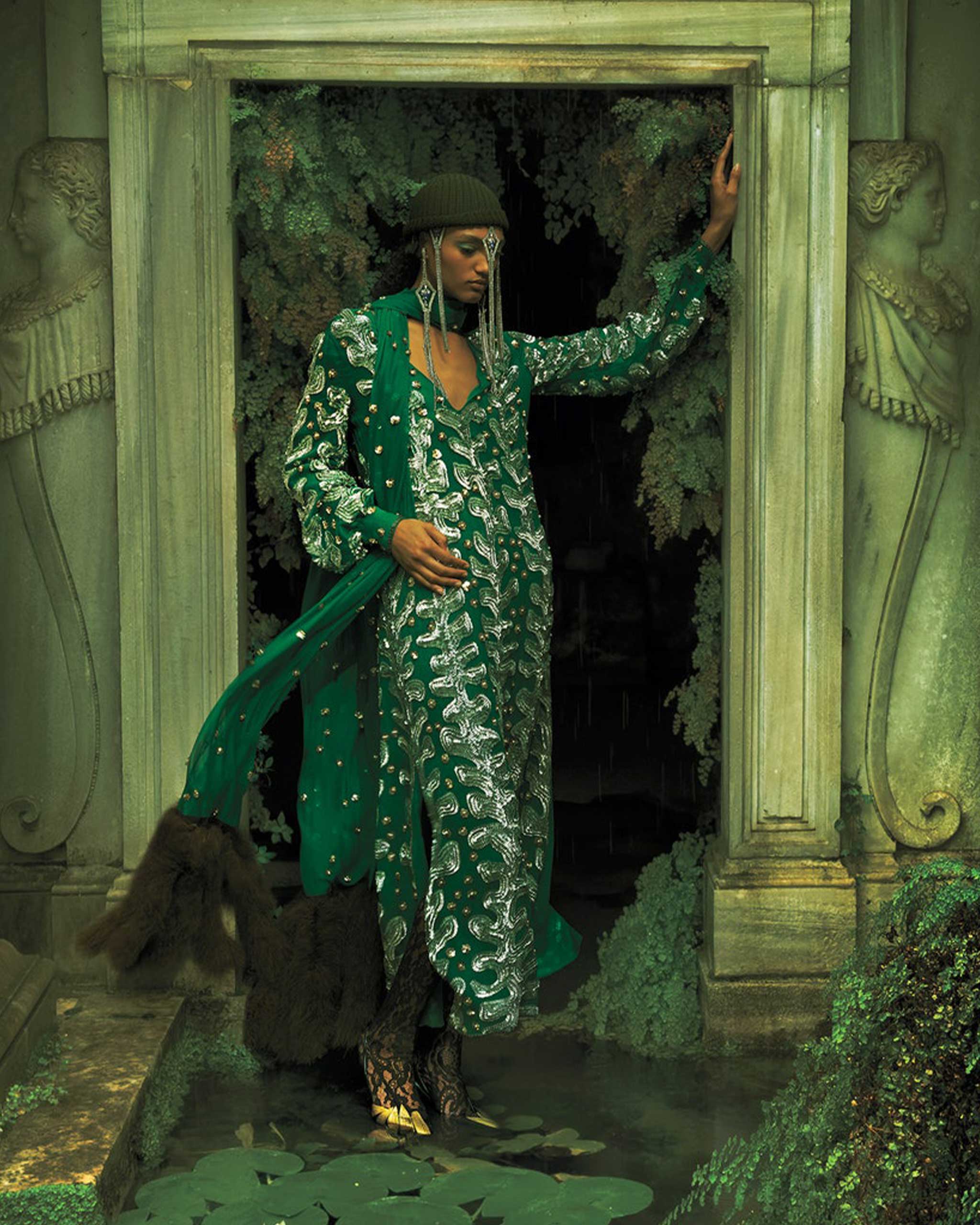

ANSWERED PRAYERS

Michele’s unfettered approach to designing Valentino is being fed by Rome. “It is about God,” he says of his hometown, “but it’s also about decadence and beauty and richness and love affairs.” The result? Otherworldly clothes.

When Alessandro Michele was growing up in Rome in the 1970s, one of his favorite pastimes was to rummage through his mother’s closet and to run his hands over the rustling taffeta, glinting sequins, and other adornments of time past. Michele’s mother worked as an assistant to an executive at a film-production company, a career that called for a glamorous self-presentation, and one gown particularly captured the young Michele’s imagination. Fashioned from crepe de chine in the style of Valentino, it was full-length and high-necked, falling straight down in a manner that reminded Michele of a candle. The front of the dress was entirely black, which Michele’s mother considered reliably chic. Embroidered on its reverse, however, was an enormous pink and lilac butterfly—an elegant yet subversive gesture, suggesting metamorphosis and transient beauty. Michele’s mother explained that she had bought the gown for a premiere; it seemed to him, he later recollected, “like she was telling me: ‘I wore it in a world that now no longer exists.’ ”

Four decades after those closet explorations, Michele last year came into possession of another sartorial treasure trove: the archive of the house of Valentino, to which he was appointed creative director in the spring of 2024. On his first day at the Valentino offices, in a late-Renaissance palazzo on the Piazza Mignanelli in Rome, Michele immersed himself in an extraordinary storehouse of garments, shoes, and other objects, all of them constructed with an exquisite lightness that belied an almost architectural rigor. In his former role as creative director of Gucci, a position he held for almost eight years until late 2022, Michele had established himself as a consummate curator, reshaping that brand with his magpie taste for the vintage and the bohemian and dressing his aficionados in garments that looked like they’d been found in English church-hall sales, or had been sourced from the cast-off wardrobes of Italian nobility. Being loosed into the Valentino archive—and being granted access to the skilled technicians whose know-how underpinned its remarkable contents—gave Michele an unprecedented opportunity: to feed his own imagination by handling, weighing, and reconceiving the material legacy of his vaunted predecessor.

On a late Saturday afternoon in September, just under six months after that first day in the archive, Michele was in Paris, at the Valentino offices on the Place Vendôme, where he was putting the finishing touches on what would be his first ready-to-wear runway presentation for the label, to be shown the following afternoon. A few decisions remained to be made about accessories and footwear, and last-minute adjustments to hem lengths or necklines. Michele sat on a chair at one end of what had once been a grand reception room, with high ceilings and gilded plasterwork. Long tables were laden with accessories: turbans, eyeglasses, and bags, including a selection of clutches that looked like porcelain ornaments in the shape of a kitten. Members of his team sat alongside him; his partner, Giovanni Attili, hovered in the background. At the far end of the room, positioned in front of a huge, framed mirror, was an even more enormous mirror. As each model walked toward him, Michele could simultaneously see the outfit from the front and the back, so as to survey its internal consistency and subversiveness—the dialogue between, as it were, high black neckline and vivid embroidered butterfly.

The atmosphere was calm. “It’s a mess,” Michele joked, when I first joined him and his team. “We can relax a little, because it’s almost done.” Michele, who turned 52 in November, was dressed in blue jeans, a Black Watch plaid shirt, and a pair of red-and-white Vans. His hair tumbled about his shoulders, like Christ as painted by Caravaggio, restrained only by a loose braid on each side. His wrists were so heavy with bracelets—linked cameos, glittering diamanté, multiple bangles—that he jingled every time he made an adjustment. The models, too, were adorned according to Michele’s aesthetic of quirky abundance. “Try to walk with the hands in the pockets,” he instructed one, dressed in a nut brown, calf-length skirt, high-neck blouse, and fur-trimmed jacket, all made from the same patterned silk-cloque fabric from the Valentino archive; she also wore a pair of John Lennon sunglasses from which dangled gold sequins, and a weighty gold chain necklace with a glittering pendant, like a rapper’s trophy combined with the prized heirloom of a dowager duchess. “Is it difficult to stand up straight?” Michele asked another model, who teetered in black-and-gold strappy shoes worn with white lacy tights, a sequined teddy, and a ruffled georgette-crepon negligee—the kind of outfit suitable for ordering late-afternoon room service of caviar and oysters from the Beverly Hills Hotel. “Better to keep walking,” Michele told her, sympathetically.

Another model emerged wearing an outfit that flirted with conservatism: high-waist, tailored gray pants with a boxy cream-colored polka-dot jacket. The jacket was fastened with a satin bow in the shade of red that Valentino Garavani, who designed the clothes that bore his name for 45 years before retiring in 2008, made his own decades ago; it was accessorized with gloves constructed with delicate black netting punctuated by embroidered white dots. The straitlaced cosplay was, however, undermined by punkish jewelry: a substantial diamanté nose ring, as if fashioned for an imperial bull, as well as a jeweled crescent shape suspended from the lower lip—S&M for the visage. There was a hubbub and a flurry of googling around the model when someone pointed out that, with her heart-shaped face and her long brown hair, she resembled Isabelle Adjani. The girl blushed at the comparison, and smiled so much that her lip jewelry fell off.

Red is cardinal in the Valentino universe, but in the view of Alessandro Michele, seen here in his office at the house’s Rome HQ with model Ali Dansky, not everything has to be so bright. “I like this dust around the brand. The dust is precious.”

For several hours, the team worked steadily, Michele sustained by an early-evening plate of thin slices of prosciutto. “Are you tired?” he asked a woman wearing a yellow Valentino sweater with a tape measure strung around her neck—the head of the seamstresses, who were toiling on adjustments one floor up. The quality of the work Valentino Garavani had commanded, Michele told me, had been a revelation. He showed me a strapless, floor-length, silk-chiffon dress in a cerulean blue patterned with polka dots; it had a bodice ruched horizontally, with a burst of ruffles at the dropped waist, below which fell a columnar skirt of narrow pleats, with more cascading ruffles swirling below the knee. “They are so complicated,” Michele said, of the varying pleats. “It’s like an origami. It’s unbelievable. He had this very specific way of being an engineer.” I was puzzled as to why Michele was using the third person: Was the dress a close reproduction of something from the archive, or something new? Was this Valentino Garavani, or Alessandro Michele?

“This is him, with me,” Michele replied. “It’s almost him. I tried to make it a little bit different. Sometimes I try to replicate the same, because it’s so fascinating. But I think that we are both in the same dress.” The gown looked like nothing I’d seen anyone wearing for decades; it could have come from the early-’80s wardrobe of Princess Diana. “I like it because it seems very démodé now, but the things that look old and démodé are, like, the best,” Michele said. “Also, in a month, they are going to be super fashionable.”

That metamorphosis—from démodé to utterly of-the-moment—began the next afternoon, when the collection was shown, not in a chic central-Paris location, as had been Valentino’s practice, but out on the Périphérique, in a martial arts venue that had been reconceived for the occasion. Guests and friends of Michele including Elton John, Harry Styles, and Hari Nef entered on cracked-mirror flooring and sat on armchairs and chaises swathed in dust sheets, as in a dilapidated mansion awaiting renovation, haunted by elegant ghosts. The cavalcade of models walked a snaking path between the onlookers, offering an intimate display of rich brocades, draping furs, billowing chiffon, delicate lace, glittering sequins, and tumbling ruffles over a mournful soundtrack of the 17th-century song “Passacaglia della Vita,” about the transience of life. When the blue dress appeared, about two thirds of the way through, its wearer was uncharacteristically unencumbered, bare-headed and virtually makeup-free—like a child who has just stepped into a gown from her mother’s dressing-up box. As she walked upright, the long column of the dress fell straight; mirrored in the fragmented floor, the skirt’s swirling complications of chiffon shimmered and fluttered, alive like a pure blue flame.

Almost two months later, I caught up with Michele at his office in Rome. Furnished with Michele’s own 19th-century double desk and 18th-century daybed with yellow satin cushions, the room was a palimpsest of its earlier occupants: from the late-16th-century coffered ceiling to the 19th-century murals to the faux boiserie wallpaper installed by Valentino Garavani in the 1980s and now wrinkling with age. “It’s a kind of creepy conversation with the beautiful ceiling,” Michele said. “I like the mess.” He was eager, he added, to explore what relics of past centuries had been covered over by Valentino’s now vintage wallpaper.

“The things that look old and démodé are, like, the best,” Michele says. “Also, in a month, they are going to be super fashionable”

I first met Michele in Rome in the spring of 2016, a little over a year after he had been named creative director of Gucci. On this morning, he appeared little-changed, with the same luxuriant beard and enviably thick, dark, center-parted locks, though on this occasion he wore his hair in a pair of tight braids. The only difference I noticed lay in the jewelry that heavily bedecked his fingers; rather than rings of silver, as he had been wearing eight years earlier, Michele had upgraded to warmly gleaming antique gold. He wore a burgundy-colored cashmere sweater and baggy pants made from wide-wale brown corduroy. Around his neck was a swath of necklaces: a bib of 18th-century neoclassical cameos; a string of wild seed pearls; and a long rope of turquoise ceramic beads with dangling floral decorations which dated to the late-Ptolemaic era. It was not, he acknowledged, a piece for everyday wear: One missed mouthful at the lunch table might inflict damage that had been avoided for 2,000 years.

Michele’s personal charisma is considerable: He is open, engaging, and intellectually curious. “You can spend a second with him and it’s like spending three days with someone else,” his close friend Elton John told me in an email. (John also noted another of Michele’s seductive attributes, undetectable in photographs: his penchant for a fragrance first manufactured almost 200 years ago by the Florentine apothecary Santa Maria Novella.) In his years at the helm of Gucci, Michele looked entirely at home alongside Jared Leto or Harry Styles on the red carpet. But before his elevation, Michele, who had worked at the company for 13 years, had been an unknown. Having worked as second-in-command to Frida Giannini, his immediate predecessor as creative director, but also under Tom Ford, who in the 1990s had made Gucci synonymous with sensual, ’70s-style sleekness, Michele had an encyclopedic knowledge of the brand. In the top job, he added to that his own idiosyncratic aesthetic sense, which merged a fascination with Renaissance ornamentation, Baroque drama, 20th-century punk, and dozens of other influences.

At first, Michele’s reenvisioned Gucci was greeted with wariness, but before long his vision was enthusiastically embraced by both critics and consumers. Michele’s madcap creativity was, though, married to a solid work ethic. “The great secret with Alessandro is that he’s really someone it’s fun to be around—there’s always time for a joke—but there’s always seriousness,” Michela Tafuri, who has worked with Michele for much of the past two decades, told me. Ginevra Elkann, a filmmaker and friend and neighbor of Michele’s in Rome, told me, “He looks very exuberant, which he is, for sure. But there’s something quite tidy that you wouldn’t expect—something organized, and precise. He’s not all over the place.”

Michele’s organization and hard work paid off for Kering, the parent company that owns Gucci; the brand’s revenues grew during his tenure from just under 4 billion euros to around 10 billion by the time he and the company parted ways, in late 2022. “I left the company because there was something that was not working anymore,” Michele told me. The growth was on a scale that was no longer human. “It’s impossible—it’s not natural,” he said. “The best growth is that you grow slow—you must care about the way you grow. It’s like a body. It needs time.” The pace was unsustainable for Michele, personally and even creatively. “I was risking being a prisoner of that place—always with the same people in the plane, in the hotel. I was inside a bubble a little bit,” he told me. Valentino, on the other hand, reported revenues around a tenth the size of Gucci: a boutique operation by comparison.

A gleaming red bow offsets a gilded confection of ruffles, transparency, and golden embroidery like ancient scrolls worn by model Jiahui Zhang—seen here at Rome’s Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia.

Stilled by a yearlong noncompete agreement, Michele devoted himself to other passions: He has restored an apartment in a celebrated Roman palazzo distinguished by its own medieval tower; it is now filled with objects from Michele’s collections, which include Renaissance paintings and delft glazed tiles. He has set about the restoration of a castle on his country estate in Lazio, north of Rome, where he has bought up a swath of countryside to save it from the encroachment of industrial pig farming. Michele’s real estate portfolio does not yet rival that of Valentino, who circulated between his Roman villa; a château outside Paris; bolt-holes in New York, London, Capri, and Gstaad; and his yacht. Michele has, though, acquired an apartment on one floor of a 15th-century Venetian palazzo, showing me in a photo on his phone how it is bordered on two sides by canals. “I like beautiful places,” he said, helplessly. “I don’t care about cars, or nothing like this—the only thing I really care about is historical places. I like the places where people died, people lived.”

When Pierpaolo Piccioli, who spent 25 years at Valentino, departed the role of creative director in 2024, Michele was the obvious choice, Jacopo Venturini, the company’s CEO, told me. “I knew that he loved working on an archive, and at Valentino, we have a very big archive,” Venturini said. “Valentino is not an empty box. It’s not a brand where you can do whatever you want, because we have a past.”

Valentino Garavani and the label that he, along with his business partner and former lover, Giancarlo Giammetti, established, was a part of Roman history. Having set out in 1960 to create an haute couture house equivalent to those in Paris, Valentino dressed princesses and the wives of presidents, and those who aspired to look like them. As a teenager growing up in Rome, Michele had been more influenced by music, and the concomitant innovations of a designer like Vivienne Westwood, than by haute couture of the sort that Valentino created. But Valentino himself was a grand personage about town. “He was familiar, like the pope,” Michele told me. “Sometimes the pope was going through in a car, and so was Valentino. In Rome, you have such an easy connection with power—you are in touch with the Roman Empire, and a long human story. I like to put Valentino together with the pope, because Rome is about God, but it’s also about decadence and beauty and richness and love affairs.” Michele has only met Valentino, now 92, in passing, years ago, though the elder man texted the younger when he was first appointed.

“I didn’t really talk with Mr. Valentino, but it’s like I spoke with him, staying in his house—you can get many things from the relics, the pieces of his life,” Michele said. “They can also tell you a very different story. They can tell you things that maybe he would never be saying in front of you—about his delicate soul, and his idea of freedom.”

While Valentino’s customers were often establishment figures, Valentino himself was far from conventional or conservative, Michele noted. “We think of him as a very classical man, but that’s so wrong,” he said. Like Yves Saint Laurent, Valentino only became considered the standard of elegance because of his innovation. “With all the change they built in the culture, they became the culture,” Michele said. “So we approach them as classical. When you see a lady with a fuchsia color shirt and a black velvet skirt you say, ‘She’s chic, she looks so classical, so Saint Laurent.’ Or when you see a lady with a chic ruffled dress, we say, ‘She’s so Valentino.’ But they did many revolutions. We forgot. Valentino, he lived his life as a gay man in the ’70s. Nobody did, in the fashion world. He did it in a way without regrets.”

“I’m always fighting with the boundaries. I am always trying to be like water, going through the little space to destroy the things in the boundaries”

In Paris, Michele’s collection, and the atmospheric setting in which it was shown, had been greeted with delight and excitement by critics and fans who appreciated the way in which Michele had combined his own aesthetic of maximalist richness with Valentino’s legacy of refined craftsmanship. Michele was mostly pleased by the reception, though when I met him there two days after the show, he had been scrolling through some less laudatory takes on social media, where some observers complained, with considerable vitriol, that he was simply replaying what he had done at Gucci. “It’s a very interesting thing about our time—that people are so violent against people that are free to do what they want to do,” he noted. One commenter had been railing against Michele’s playful accessories: “She’s just screaming for a lady with a kitten bag!” he said. He suspected that his critics were motivated by their own sense of being disempowered. “The more free you are, the more people go crazy,” he went on. “I think people feel themselves to be not free. And if you are managing your freedom, they are like, ‘Why are you doing what you want, and I can’t do what I want?’ That’s interesting.”

During his sabbatical, Michele completed a book, La Vita delle Forme (The Life of Forms), with Emanuele Coccia, a professor of philosophy. Michele has always offered a critical, theoretical lens upon his creative output, influenced in part by the intellectual work of Attili, his partner, a professor of urban planning. During his time out from working, Michele sometimes snuck into Attili’s lectures at the university in Rome. “In my next life, I want to study all my life,” he told me. Attili encouraged him to take his time after leaving Gucci. “He was the one who said, ‘We can change our life. You can change your life. I’m fine.’ ”

In the book, the English-language publication of which is forthcoming, Michele gives an account of the ideas that underlay what, in the past few years, he has sought to explore on the runway. These include his then innovative embrace of nonbinary gender identities and their expression—a gesture that has in the years since become almost commonplace. In each of his collections, he writes, “I pursued an ideal of beauty and ambiguity that revives in bodies forgotten identities.… From the beginning…I hybridized everything I encountered: as a way to include diversity within each single form.”

Inevitably, Michele told me, his work at Valentino would continue the explorations he had undertaken at Gucci: His intellectual and aesthetic sensibility is constant, even if the material heritage within which he is working is a different one. “I think it’s going to change a little bit—half and half,” he told me. “I mean, keeping the soul, but making the brand more alive. But I like this dust around the brand. The dust is precious.”

When Michele began to plan his first haute couture collection for Valentino, he could not stop thinking about a painting he bought a few years ago that hangs behind a dining table at his home in Rome. Painted by François Quesnel, who lived in Paris in the late 16th century, and whose works Michele collects, it shows a woman wearing a dark gown, narrow at the waist and cut very low on the bodice, her face and décolletage framed by a delicate white upright collar, her neck adorned with a pearl choker.

“She was a rich woman,” Michele explained over a lunch of fried artichokes and Dover sole at Ristorante Nino, an old-school spot close to the Valentino office. “People think that the black dress is just about mourning, but it was about richness, because it was the most precious color ever. This is kind of a fake black—dark aubergine.” What appealed to Michele was not just the color, but the symbolism encoded in the painting. On the wall behind her hangs a portrait of herself as a younger woman, and by her side stands her young daughter—to demonstrate her maternal role. From her waist, a gold chain suspends a locket that contains a portrait of her late husband. “She had this legacy of this big kingdom from him,” Michele said. “It’s a very interesting way to say, ‘I am a powerful woman.’ ” He had sent an image of the painting to the head of the couture studio. “I said, ‘Let’s start from here. Maybe we will go far from this, but let’s start.”

Michele’s unfettered approach to designing Valentino is being fed by Rome. “It is about God,” he says of his hometown, “but it’s also about decadence and beauty and richness and love affairs.” The result? Otherworldly clothes.

Michele made gorgeous one-off gowns while at Gucci—like the pink, floor-length silk-chiffon dress with a deep ruffled neckline and appliqués of stars and moons that Florence Welch wore to the Grammys in 2016, of which she told me, “I felt so comfortable—and I felt so myself. Alessandro saw what was beautiful and exciting about how I wanted to dress.” Even before his first couture collection for Valentino (the show takes place this afternoon in Paris), Michele demonstrated his interpretation of Valentino virtuosity by dressing Apple Martin, the daughter of Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin, for Le Bal des Débutantes in Paris in November, fashioning a strapless sky-blue gown with six tiers of silk plissé chiffon. (Paltrow and Chris Martin wore Valentino too.) Today’s couture show is, though, Michele’s first opportunity to offer an entire collection of one-off, handmade gowns fashioned not for performing artists or their offspring, but for the wardrobes of ladies of means—the modern-day equivalent to the woman in the portrait over his table.

It required a cognitive shift to not think about how to replicate a design, as he would reflexively do for ready-to-wear, Michele explained; the technical prowess of the Valentino tailors challenges his imagination in a way that is almost metaphysical. Haute couture, he said, “is a dress that doesn’t answer to the real life.” He went on: “You can put into the dress whatever you want, with no boundaries. It’s maybe hard, because I like to have boundaries. I’m always fighting with the boundaries. I am always trying to be like water, going through the little space to destroy the things in the boundaries. Here, there is no one against me.” He went on, “Freedom is such a delicate thing, you know. It means…completely naked. It means…completely who you are.” There was another meaningful difference in the process: With ready-to-wear collections, Michele’s team presents him with a model fully dressed, as at the fitting in Paris. But for couture, he explained, the model stands before him almost naked, while the seamstresses build the dress upon her—clustering around the disrobed body in an atmosphere that Michele described in sacramental terms.

“Couture is the seed where everything started—it’s an archaeological rite that we are keeping alive,” he told me. “When I see the tailors surrounding that girl and the dress with me, keeping alive that rite, I am feeling like there’s a spirit, a very strong and powerful spirit, that you must preserve. Like a religious thing.” The seamstresses, he said, “know how to manage the thing, like nuns, like the vestali”—the priestesses of ancient Rome who tended to the sacred flame in the temple of the goddess Vesta, the ruins of which stand in the Forum, a short walk away from the Valentino palazzo. The comparison reminded Michele, once again, of the fleeting passage of life and the brevity of individual existence against thousands of years of history. More prosaically, it reminded him of the transitory nature of fashion. Of the culture that has become his inheritance at Valentino, he said, “They want to keep and preserve the flame forever, and I’m going to be one of the people that try to manage the flame. But I’m going to be just one. The flame is the thing that you must keep alive.”

In this story: hair, Shiori Takahashi; makeup, Yadim; manicurist, Silvia Magliocco; tailor, Viola Sangiorgio. Produced by AL Studio and Kitten production.

This article was originally published on Vogue.com.