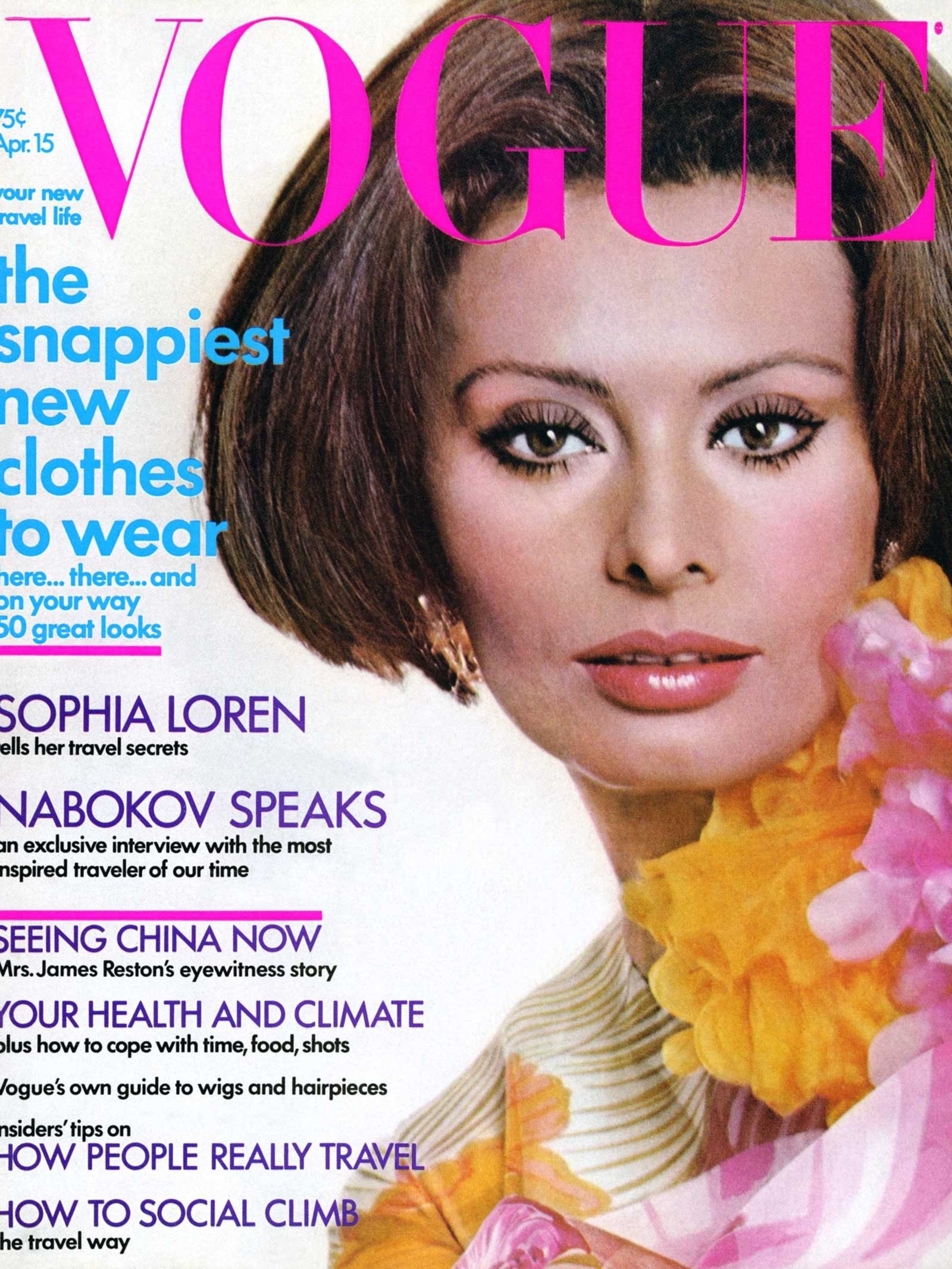

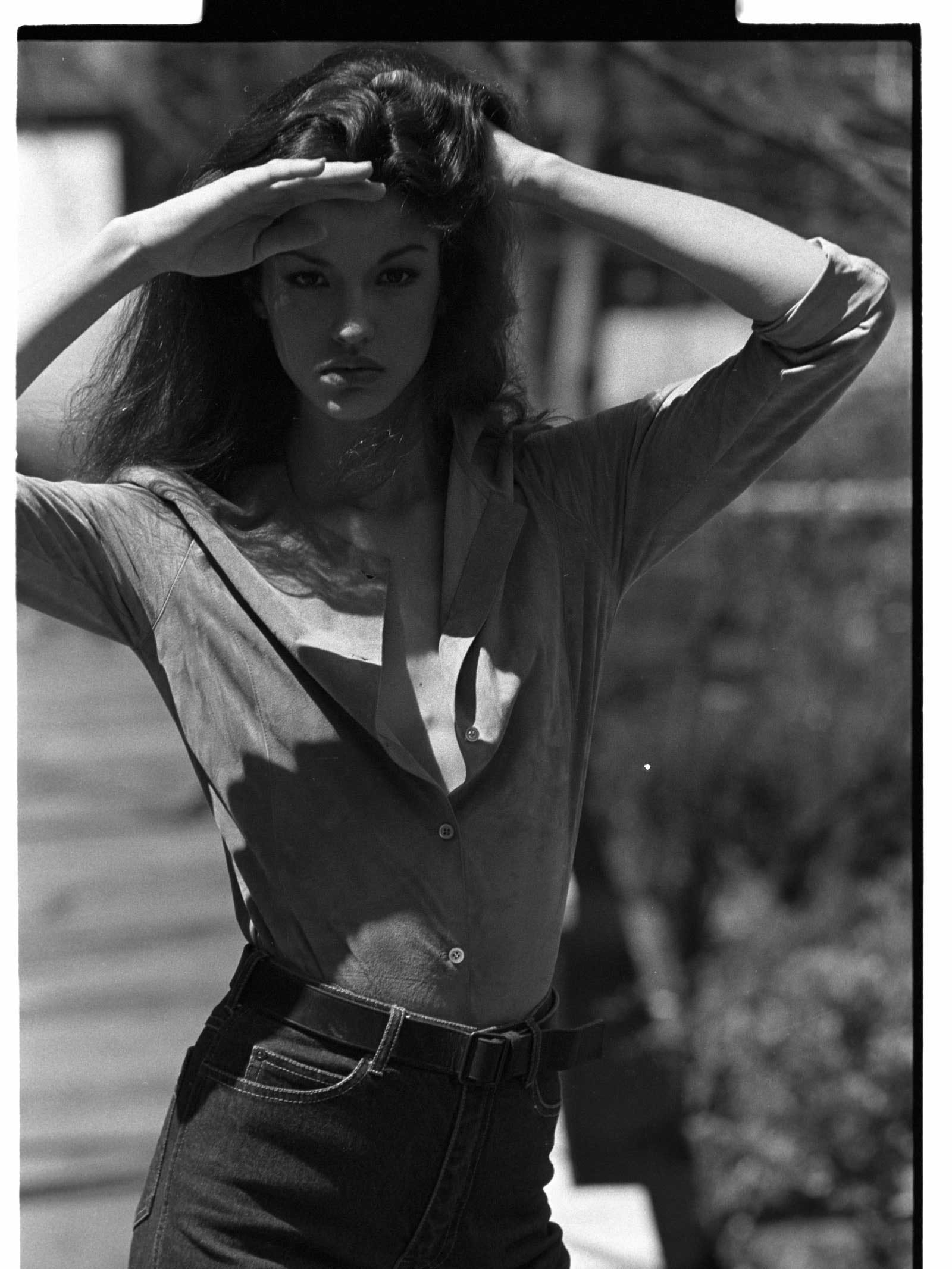

Lauren Hutton in “blaze and feathers from Norell. ”Photographed by Bert Stern, Vogue, November 1, 1971

The 1970s was the decade for the woman, capital W. As women’s liberation marched on (in 1970 more than 50,000 people participated in the first women’s equality march, the Women’s Strike for Equality, in New York City), the way women dressed also embraced a bold new course.

The fashion of the 1970s also put the female body on show like never before. Clothes were soft and clingy and worshipped the figure in its natural form, with much of it requiring little to no structure from undergarments. She was liberated! She wore the pants—literally! Pants, suiting, and—by the late 1970s, anyway—designer denim all became fully acceptable for just about any situation.

Though bold, 1970s fashion also possessed a featherweight touch. Metallics reigned but were subtle in Lurex and soft coppery tones; color was ever present but leaned toward sherbert hues—no neon just yet!

It was an era of easy-on, easy-off fashions for the disco and jumbo jet. In Vogue’s January 1970 issue, an article looked ahead at the new decade, decreeing the fashionable verdict: “Shawls, capes, ponchos—anything that can be wrapped, strapped, or rolled around the body is home free in every way.”

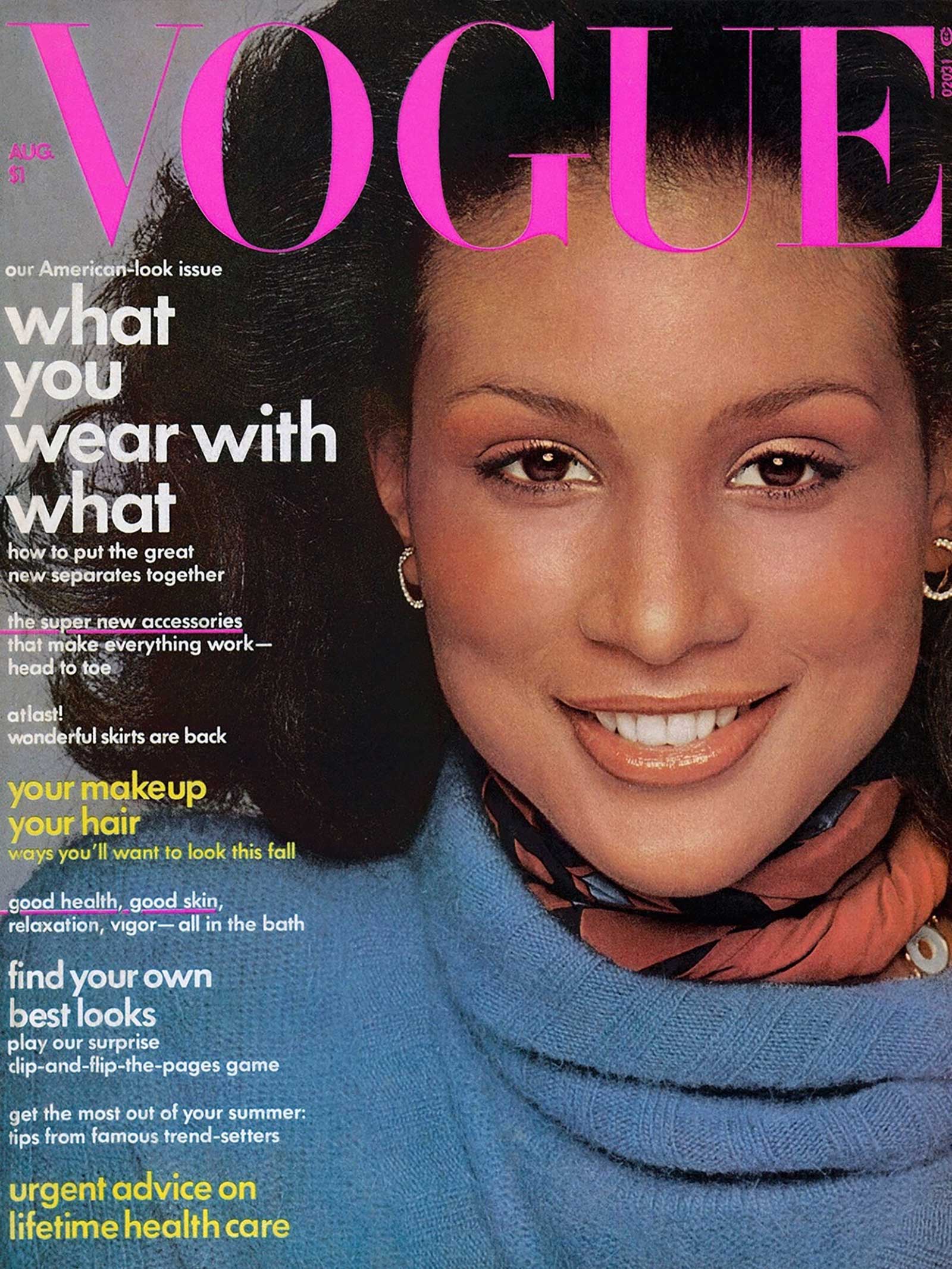

By 1974, Vogue reached a milestone. For the August 1974 issue, Beverly Johnson made history as the first Black woman to grace a cover of Vogue.

Women’s Trends of the 1970s

New Romanticism: Designers Get Dreamy

At the start of the decade, hippie culture still had a hold on fashion. While some embraced the folksy spirit of the movement with thrifted pieces and ethnic garb, others took a more high-fashion route that veered more prairie idyllic than earthy hippie. The look was less defiant and more romantic and was championed by London-based designers and labels like Zandra Rhodes, Ossie Clark, and Laura Ashley, as well as the San Francisco–based Gunne Sax run by Jessica McClintock, and the New York-based Giorgio di Sant’ Angelo.

Kicking off the new decade, Vogue’s January 1, 1970 issue directed its readers to embrace a sensual, free-spirited ease. “All languorously falling things—and with lots and lots of long, dangling fringe to keep the languor lingering…anything that makes you dream a little bit about yourself.” In the spread: an image of film star Natalie Wood wearing a couple of Zandra Rhodes looks described as “yards and yards of purest fantasy—designs that summon the delectable world of Russian fairy tales and English storybook pantomimes.”

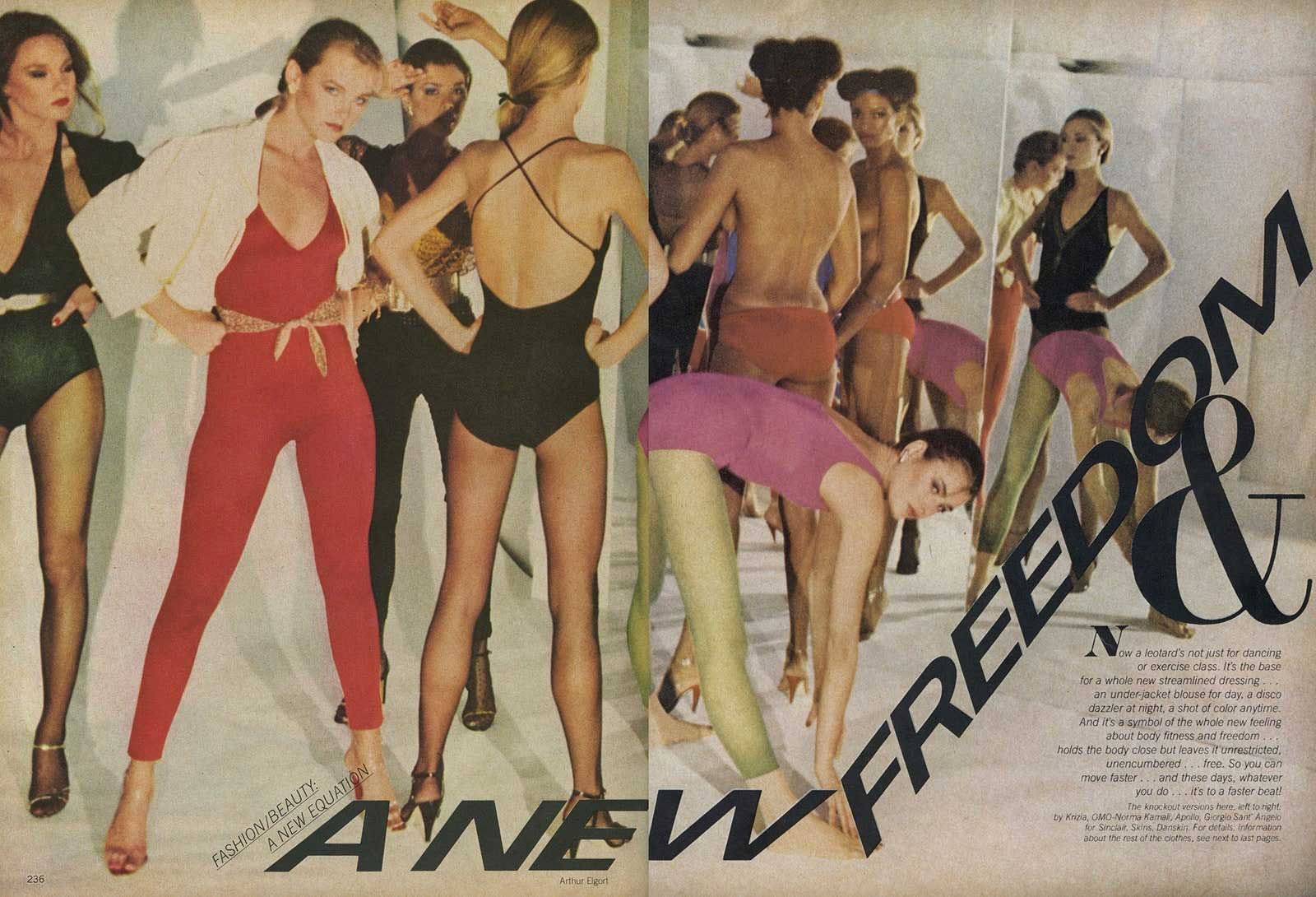

Sportswear Takes Over, Tailoring Softens Up

If the fashion of the decade could be summed up into a feeling, it would be soft: Sonia Rykiel and Missoni were introducing novel, luxurious knitwear; Halston had Ultrasuede separates and clingy jersey; Calvin Klein offered whisper-thin satin slips and double-knit jersey suiting; Fiorucci did stretch denim; and Diane von Furstenberg introduced her second-skin wrap dresses. All shared a supple quality, and the female body was on glorious display in slinky pieces that skimmed the figure. An August 1977 Vogue article put it succinctly: “Sportswear Dress: The Word Is Soft.”

For sportswear—a burgeoning category that has less to do with athletics and more to do with easygoing separates—softness was key. Comfort was paramount in all clothing, especially as women entered the workforce in droves and needed smart yet practical fashion for the job.

Polyester, the Fabric of a 1970s Life

Polyester peaked; if there was one fabric that the ’70s wrapped itself in, it was polyester. In double-face knits, the fiber brought the era’s fashionable silhouettes to life: pointed collars, sweater-y suits, clingy separates. The rise of cheap-to-produce fabric coincided with the decline of couture: In 1968 Balenciaga closed up shop in Paris altogether, lamenting the state of couture while his contemporaries Pierre Cardin, André Courrèges, Yves Saint Laurent, and Emanuel Ungaro all poured their efforts into building ready-to-wear businesses.

Polyester made it so that the chic suiting and modish minidresses seen on the runways could be produced and sold for fractions of the price. Though the fabric had its pitfalls (a lack of breathability and a plastic odor), its iron-free, low-maintenance properties were celebrated. If the 1970s saw women’s liberation make strides, polyester (which was invented by DuPont in the late 1930s and marketed as fashionable by the 1950s) freed women from the iron. It also gave her a low-maintenance suit to wear to the office. But by the end of the 1970s, consumers began to lose their taste for polyester; its synthetic properties were no longer celebrated but disparaged.

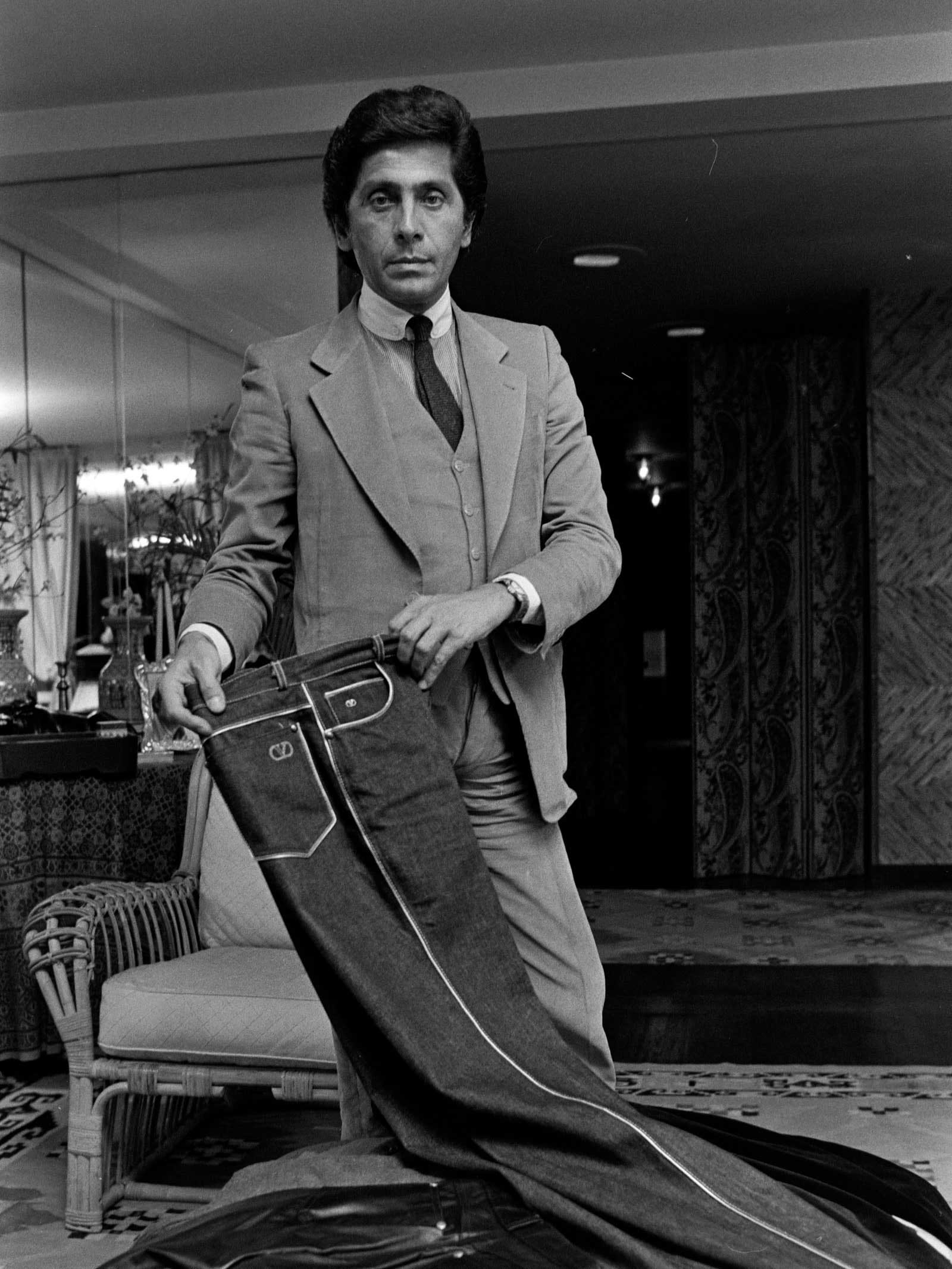

Designer Denim: Fashion Gets On Board With Jeans

In 1973, Neiman Marcus dubbed Levi Strauss the “single most important American contribution to worldwide fashion.” A lofty award, sure, but it was no less accurate. Denim was on everybody and every body. After the 1950s saw the twill fabric go from workwear to streetwear, the jean steadily took over. And by the 1970s, high fashion wanted in.

Levi’s, Lee, and Wrangler were the mainstays, but they were soon joined by Calvin Klein, Gloria Vanderbilt, Peter Golding, and Fiorucci. The designer-denim era had begun. In an article tracing the history of denim in 1978, Vogue wrote, “The lowly blue jean was apparently not worthy of a Name Designer logo. Until now, that is. Just when skeptics were saying that the blue-jean market was saturated and there was talk of the demise of denim; just when the sales of Levis were falling and many stores were reducing their markup on jeans, the Calvin Kleins and Geoffrey Beenes and Ralph Laurens and Oscar de la Rentas begin branding blue jeans with their celebrated names and initials.”

Like the model of perfume and lipsticks, it was a way to buy into a designer’s brand at a low cost. That same article continues, “Calvin Klein, who introduced his first denim jeans earlier this year…insists that ‘jeans are not dead: they’re hot and sexy and still great.’ He claims he waited to get into the jeans scene until he could get a licensee (Puritan Industries) to make them ’at a reasonable price. I want the girls who can’t afford to wear my clothes to wear my jeans.’”

In a stroke of marketing genius, Studio 54 got into the denim game a couple of years after opening in 1977 with the brilliant tagline “Now everyone can get into Studio 54.”

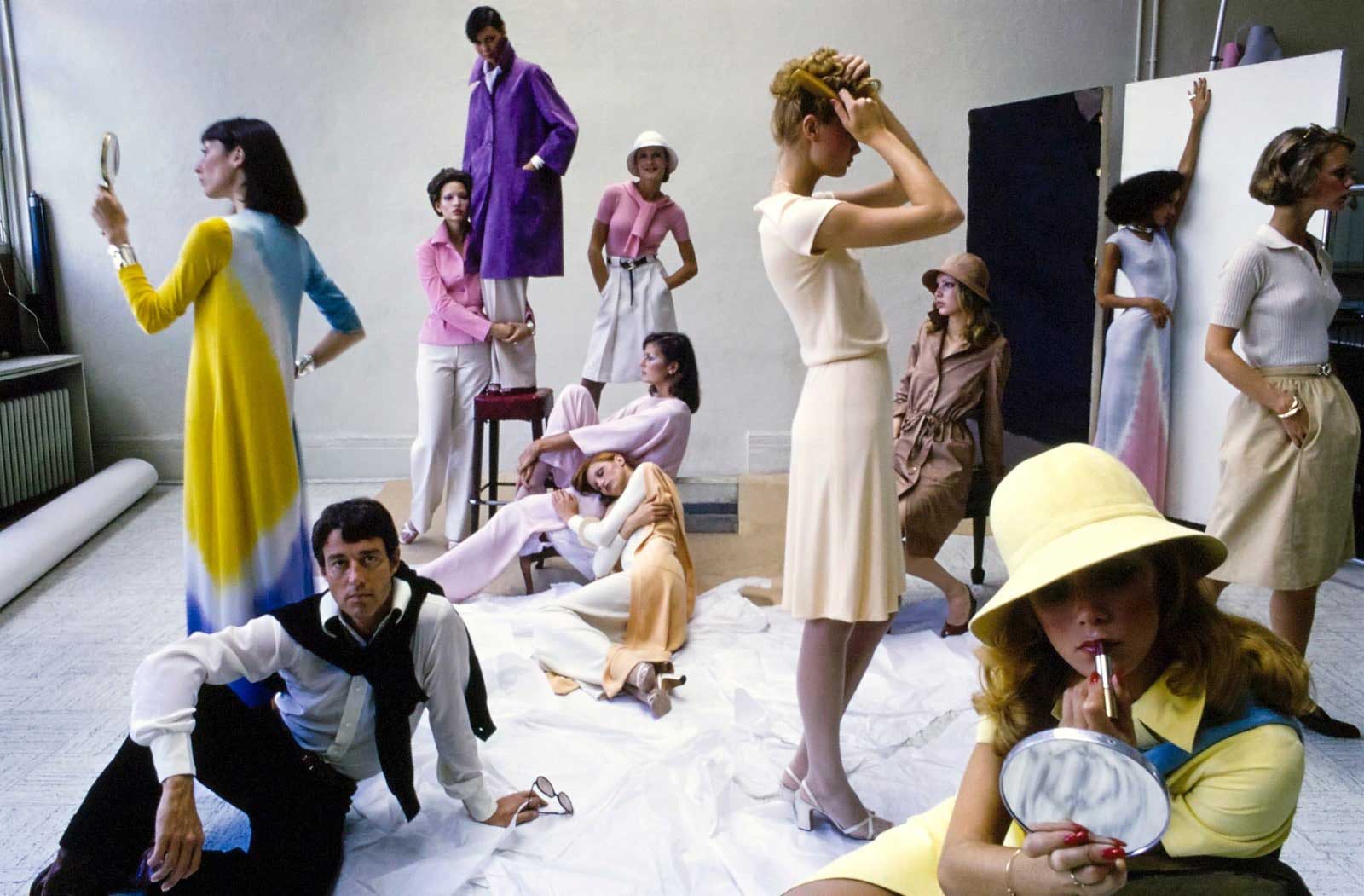

American Designers Triumph: The Battle of Versailles Brings a New Regime

Paris couture’s golden age came and went, and the 1960s saw London come onto the fashion scene in a real way. By the 1970s, it was New York’s turn. Manhattan was home to a collection of designers who not only made fashion but also set the direction for it: Calvin Kelin, Ralph Lauren, Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows, Oscar de la Renta, Halston, and Anne Klein. Each label possessed its own distinctive style, which marched to its own beat, breaking with the fashion metronome of Paris.

Eleanor Lambert (the publicist genius behind the conception of the Met Gala, Fashion Week, and the International Best Dressed List) once again did her part for American fashion by helping to orchestrate a moment. In 1973, a string of events were organized in Paris and Versailles to raise money for the restoration of the historic palace, including a fashion show of five French designers (Marc Bohan for Christian Dior, Pierre Cardin, Hubert de Givenchy, Yves Saint Laurent, and Emanuel Ungaro) and five American designers (Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows, Oscar de la Renta, Halston, and Anne Klein). Though today the fashion show has been dubbed the Battle of Versailles, at the time it wasn’t conceived of as a competition. In Paris’s eyes, there was no competition.

Reports of the fashion show—which was bifurcated into two parts, Parisians then Americans—describe a languorous Parisian portion (Rudolf Nureyev danced a scene from Sleeping Beauty, Josephine Baker performed burlesque alongside Crazy Horse Saloon performers) followed by a breezy American showcase that was tightly edited and all built up into a finale with Liza Minnelli performing Funny Face’s “Bonjour, Paris.”

In The International Herald Tribune, on November 30, 1973, Hebe Dorsey’s article “Americans Steal the Show at Versailles Gala” summed up the lasting impact of the night: “The real surprise was that American fashion has come of age. The French can no longer ignore it.”

The ’70s Do the ’40s, and Fashion Gets Nostalgic

If the 1960s looked ahead to the Space Age, by the 1970s fashion got seriously nostalgic. Perhaps it was The Godfather (released in 1972); perhaps it was Yves Saint Laurent’s 1971 Libérationn, or Quarante, collection, which was inspired by 1940s wartime fashion and the couturier’s muse Paloma Picasso (who dressed in flea-market finds). (Rummaging up wartime memories for the sake of fashion didn’t go over too well for Saint Laurent.) Regardless, tastes seemed to align on the ’30s and ’40s as a reference point. Silhouettes borrowed from the structured shoulders before Dior’s New Look, and women wore shirtwaist dresses in geometric prints.

Skimming Vogue’s fashion captions reveals several instances of fashion that “winks at the 1940s,” and beauty got into the nostalgia too. An article in the June 1972 issue, “The Sweeping Comeback of Dark Nails,” declared, “Ultraviolet, another classic ’40s shade, looking better than ever on ’70s nails.”

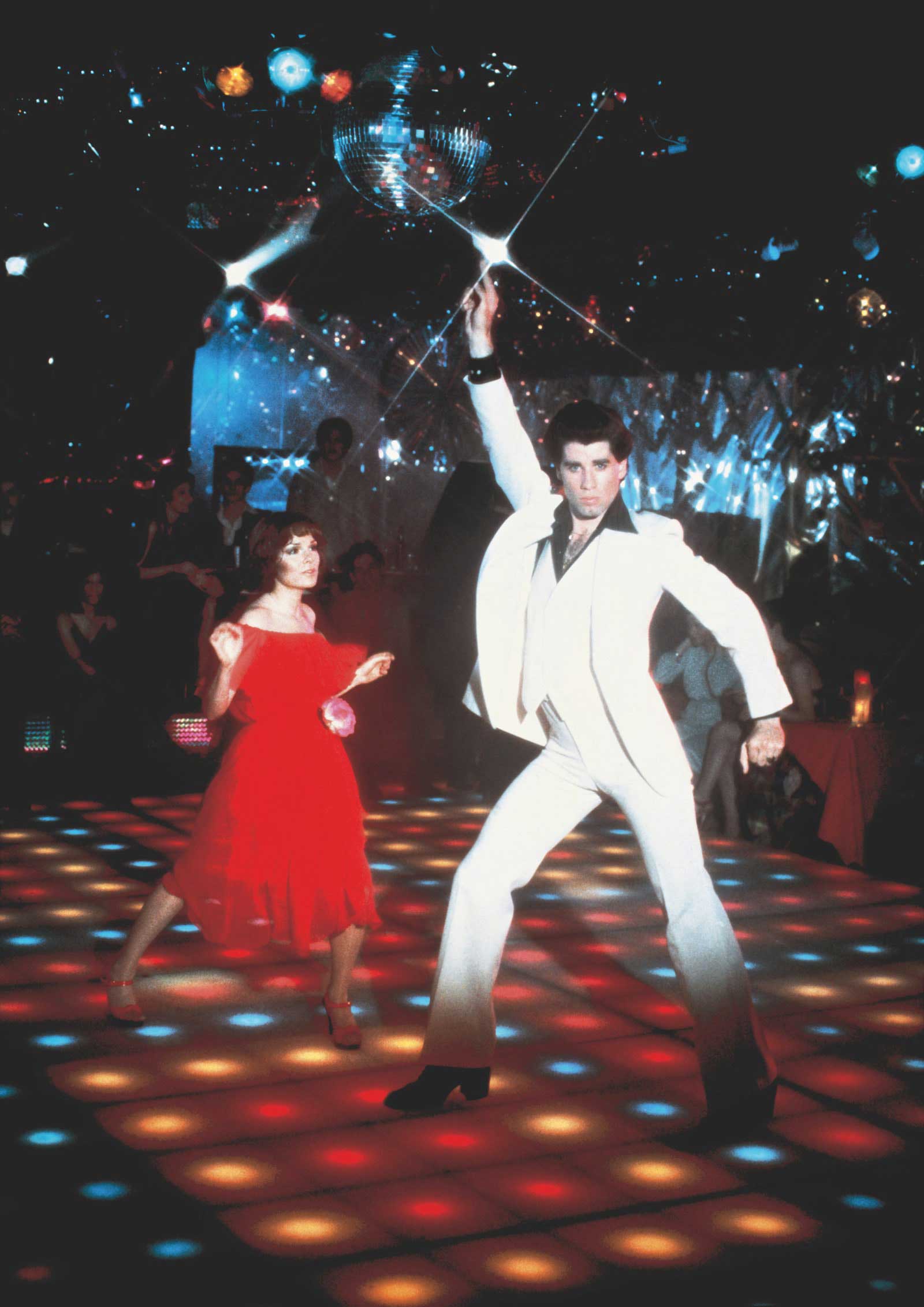

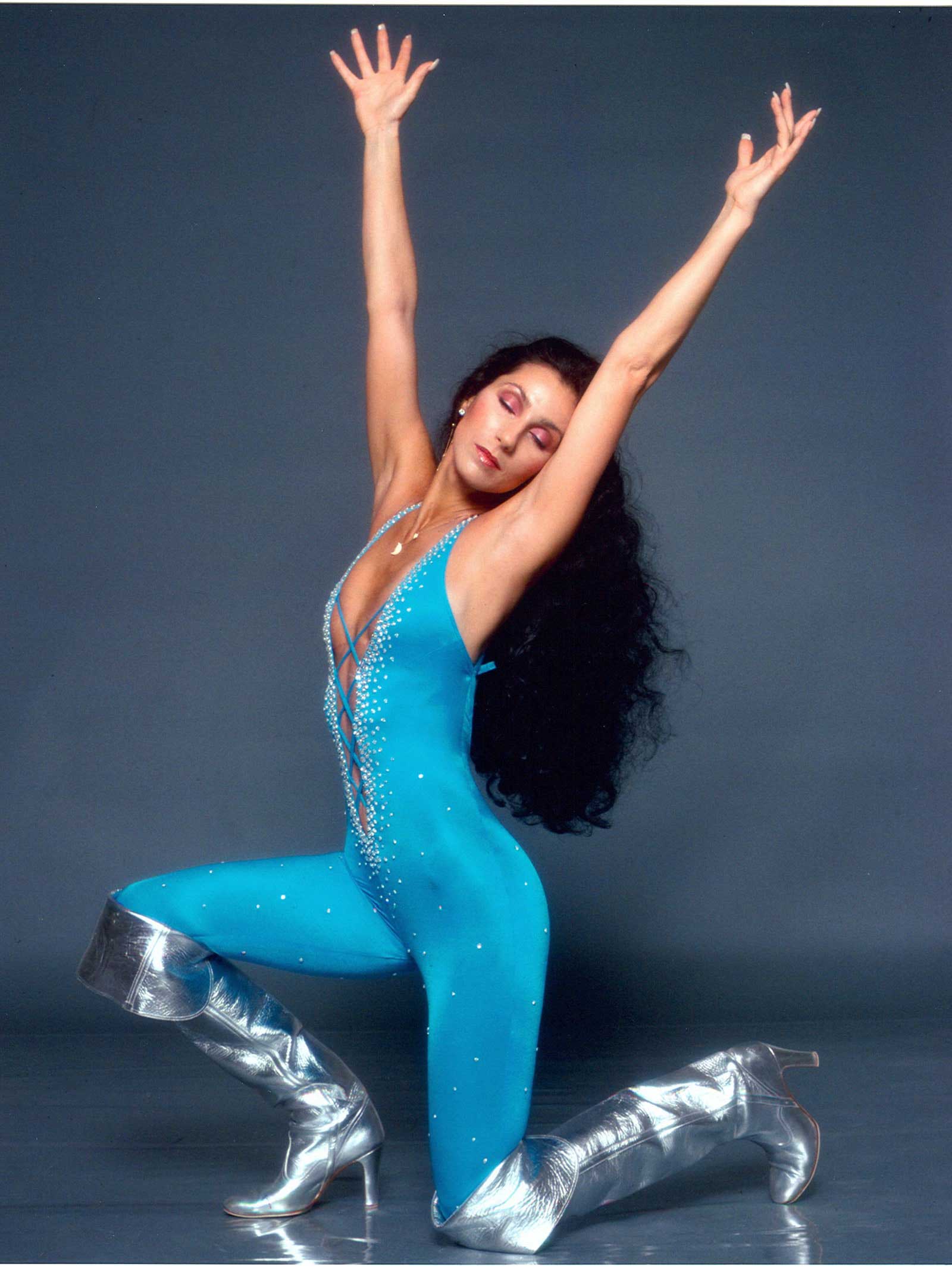

Music Influences Fashion: Disco Fever and the Rise of Punk

The year was 1977. John Travolta was boogying in the just-released Saturday Night Fever, and Studio 54 had opened in the spring to great fanfare. Disco dominated, and people needed to look the part. For women, it meant spandex and slinky jerseys that hugged every curve, cut into halter-neck tops, hot pants (new to the scene in the 1970s), pleated midi-dresses, and more. Even better if a shimmer and gleam could get caught by the lights of the disco ball; Lurex was the preferred metallic. It also meant platform heels and feathery hair. (For men, it meant disco flares and exaggerated, pointed lapels so sharp they could cut a rug.)

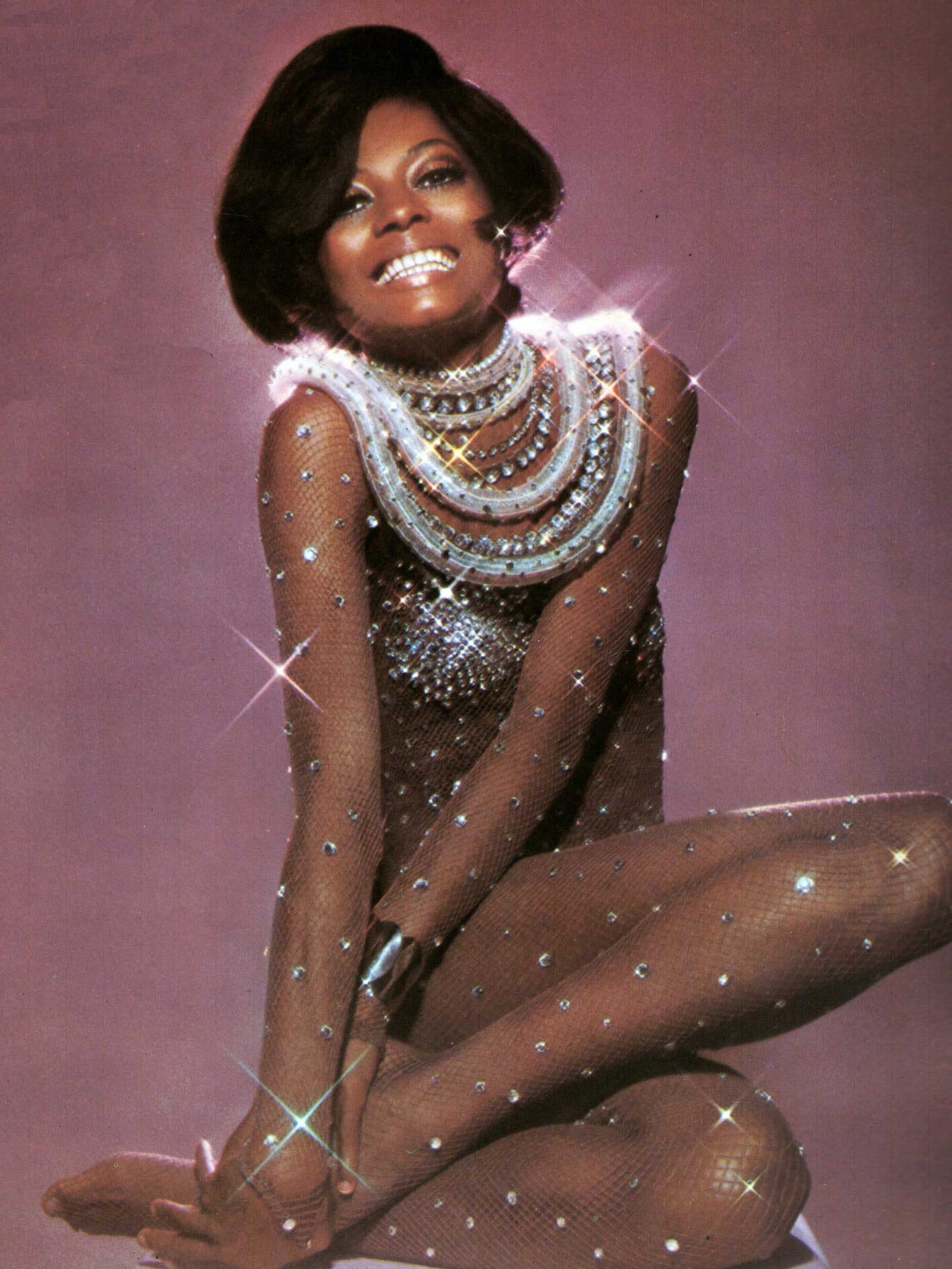

High fashion was in on the craze too. Halston and Stephen Burrows were the kings of glam disco, and Norman Norell’s stretch sequined gowns continued to allure women.

The previous year, in 1976, over in London, Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren had birthed the punk fashion movement with their Chelsea boutique Seditionaries, then Sex. Inspired by a more transgressive genre of music, the look was a rejection of the status quo: the political climate, the ongoing recession, the disenchantment with capitalist living. By 1977 Zandra Rhodes, who had begun the decade with romantic and folkloric chiffon gowns, went full-on punk with purposely tattered dresses, safety pins for fastenings, and intentional holes.

Top Designers of the 1970s

Yves Saint Laurent, André Courrèges, Oleg Cassini, Rudi Gernreich, Norman Norrell, Emilio Pucci, Pierre Cardin, Emanuel Ungaro, Geoffrey Beene, Ralph Lauren, Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows, Oscar de la Renta, Halston, Anne Klein, Sonia Rykiel, Missoni, Chloé, Kenzo, Issey Miyake, Giorgio Armani, Valentino, Betsey Johnson, Mary McFadden, Marc Bohan for Christian Dior, Tommy Nutter, Ossie Clark, Zandra Rhodes, Jean Muir, Bill Gibb, Vivienne Westwood, Norman Norell, James Galanos, Bob Mackie, Giorgio di Sant’ Angelo, Norma Kamali

Men’s Trends of the 1970s

More so than any decade before, men had plenty of muses in the 1970s, from James Bond to Mick Jagger to Johnny Rotten to Bob Marley to David Bowie to James Brown.

If one look took over the decade, it was the polyester leisure suit (a two-button blazer and slacks), which was marketed for its ease, comfort, and low maintenance. Shirts were worn tight, pants had a flare, and lapels were wide. Roger Moore’s James Bond popularized the safari suit.

David Bowie gave the world glam rock with his feather boas in his Ziggy Stardust era (Kansai Yamamoto designed costumes for Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust tour), while Mick Jagger wooed the world in his effeminate frilly pirate blouses.

In 1975, Italian designer Giorgio Armani founded his own label, which would set the tone for the decade to come.

In the Culture

On January 12, 1970, a Boeing 747 arrived at London’s Heathrow Airport—the jumbo jet’s first transatlantic commercial flight. The era of the jet set began, and fashion responded by making wrinkle-free wares.

The decade also heard from women, who demanded equality. In the summer of 1970, the National Organization for Women (NOW) organized a nationwide strike, marches were held calling for equality, and voices like Gloria Steinem and Simone de Beauvoir called for action. In 1973, Billie Jean King triumphed over Bobby Riggs in the much-publicized Battle of the Sexes tennis match.

Political unrest permeated throughout the US until the Vietnam War came to an end in 1975. In 1972 President Nixon became the first US president to visit the People’s Republic of China.

Over in the UK, Prince Charles announced he was dating Lady Diana Spencer and Margaret Thatcher was rising in power.

In entertainment, Sonny Bono and Cher enthralled audiences with their show, which premiered in 1971. Diana Ross was in her heyday, kicking off her solo career in 1970.

Onscreen, Charlie’s Angels inspired women to cut their hair in feathery, Farrah Fawcett\–esque layers and Diane Keaton’s turn in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (with costumes by Ralph Lauren) imprinted on women who wanted to suit up like the boys.

Vogue World: Paris will pair select sports—cycling, gymnastics, tennis, taekwondo, fencing, and break dancing, among others-with French fashion from every decade since 1924. The show will showcase French designers, current and past, as well as houses that historically present their collections in Paris.

For front row tickets, email [email protected]

This article was originally published on Vogue.com.