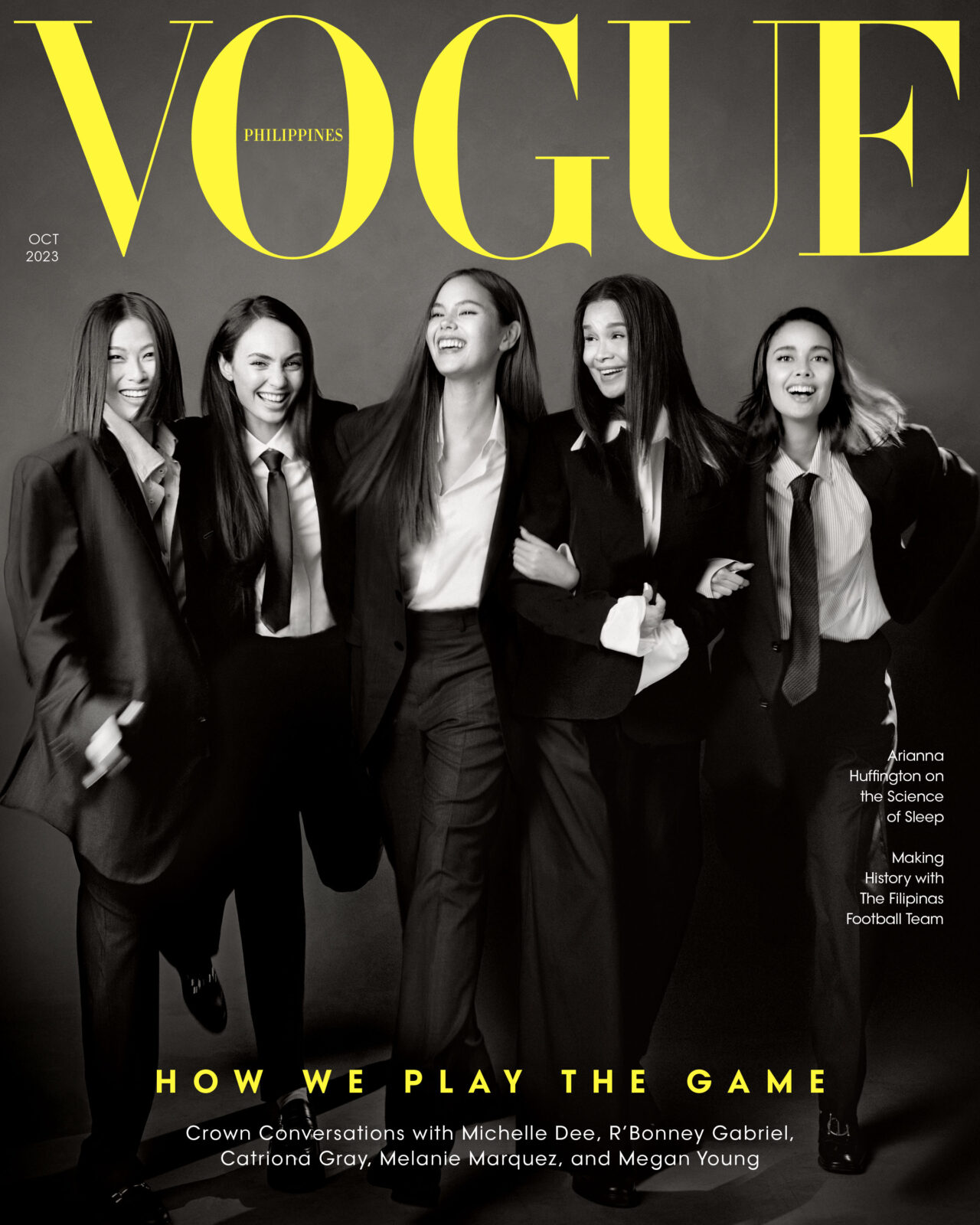

Photo by Harold Julian

Why do Filipinos, despite challenging situations, smile so easily and generously?

Like with many Filipinos, Sundays are sacred for our family.

Every week, my parents, sister-in-law, and two-year-old niece Yllize make the trip from the town in Bacoor where I grew up to the city where I now live to have an early lunch together. Walking to the spot where I usually meet them, I would see my niece already bobbing and moving her head as soon as the car stops. She would see me and break into a huge smile, a toothy grin that seems uncontainable as if wanting to burst from her face. It’s a sight that brings me joy that is unfortunately laced with sadness.

Last year, my brother, Yllize’s father, passed away suddenly, a loss that rocked our whole family and that which still echoes among us today. These weekly few hours together are meant to remind us of our bonds and for us to deal with our grief and move forward together; Sundays are sacred not because of mere religious tradition, but because they allow us to heal just a little bit every time.

My little niece, still blissfully unaware and uninformed of life’s many cruelties, continues to offer her smile generously, easily.

Our family’s situation, and the tendency to offer up a smile despite hardships, is not uncommon among us Filipinos. We do so openly that it’s become a distinguishing mark of our people. The vlogger Nas Daily mentioned this in his video 8 Days in the Philippines: “It’s so fun in the Philippines that if you go and ask random people to smile, they will smile back! Even security guards!”

While the idea of a foreigner randomly coming up to locals and demanding for them to smile does not make for comfortable optics, particularly coming from someone who has run into problems with Filipino culture in the past, it’s not entirely inaccurate.

The Filipino smile is offered generously and through constraints. Author and heritage advocate Felice Prudente Sta. Maria describes the Philippines as being “smile-rich.”

“Laughter and smiling are a pair during fiestas and celebrations. But Tagalogs have been known to insist that children learn to ‘Accept defeat with a smile.’ Cebuanos teach, ‘Smile even if it hurts.’ A stiff upper lip in response to misfortune and adversity does not seem to be a Filipino tradition. Instead, maintaining a smile is,” she tells Vogue Philippines. “While historical records about Filipino smiling are elusive, it has been a practice over generations that Filipinos smile when they are happy, sad, angered, disappointed, unsure, and want to avoid direct confrontation.”

Smiling specifically through unpleasantness has become a particular Filipino trait. From the psychologist Dr. Rea Villa’s point of view, this is a form or aspect of positive psychology. She cites Harvard Health: “Positive psychology encourages people to tap into their inner strengths and connect with others; which in turn leads to gratitude and happiness.”

Villa, a senior psychologist for the mental health technology company Mind You, lists down several factors of Filipinos smiling through hardships: “First, the Philippines is a religious country we put our biggest trust in God or a higher being. Most of the time if things get rough and challenging we call to God for help, this gives Filipinos the comfort they need,” she says, adding that this gives us a feeling of having a sense of control despite the challenges we experience.

Given that the Philippines has the third largest Catholic population in the world, this isn’t surprising. “We accept the notion that all problems are tests of faith and conquering them is our supreme recompense,” writes Bong Osorio in his column for The Philippine Star in 2018. “This conviction is displayed in the many vibrant, well-attended city or town fiestas held all over the country in celebration of overcoming long and difficult ordeals and achieving positive outcomes attributed to God.”

The Filipino smile is offered generously and through constraints. Author and heritage advocate Felice Prudente Sta. Maria describes the Philippines as being “smile-rich.”

Advertisement

Perhaps the biggest example of a fiesta that was born out of a difficult ordeal is the Masskara Festival, which is celebrated in Bacolod. (The 162 square kilometer destination in the Northwest Coast of Negros is nicknamed “The City of Smiles” for its sweet-natured people.) On April 22, 1980, tragedy struck when the inter-island vessel MV Don Juan collided with a tanker in Mindoro’s Tablas Strait on its way to Manila. More than a hundred went missing that day while 18 people died, including members of prominent Negrense families.

The city was then already dealing with its once mighty sugar industry waning. The Don Juan tragedy placed an even bigger cloud of gloom over Bacolodnons’ heads.

What was the answer of the government? Then Mayor Digoy Montalvo appropriated a seed fund and gathered artists and creatives in the city to launch a “Festival of Smiles.” During this celebration, masks are worn by those participating in the parade, with each covering prominently displaying different kinds of smiles.

Today, it has evolved to become one of the biggest fiestas in the country. It is celebrated Rio de Janeiro- or Mardi Gras-style, filled with colorful parades and wild partying. In this way, as the original organizers intended it, the event shows that no matter how bad it gets, Bacolod and its people will overcome.

Resilient nation

Facing numerous challenges like inflation, disasters, lapses in government, and the like are par for the course of a still (after all these years and administrations) developing country. “I think these factors have caused us to adapt and be more flexible. We try to look at the brighter side of things; becoming hopeful that there are beautiful things ahead of us,” Villa says.

Take the short film The Invisible Monster, a jury award winner at the 2020 Festival Iberoamericano de Cortometrajes de ABC (FIBABC). It also nabbed the Best Actor trophy for its child-narrator Aminodin Munder. The film depicts the 2017 Marawi Siege, deemed the longest urban battle in recent history. Six years ago, the city found itself in the middle of a conflict that erupted between Philippine government security forces and militants affiliated with the Islamic State.

It went on for five months, leading to millions of pesos in structural damage and more than a thousand fatalities, and forcing scores of families to live in refugee camps. It was deemed the longest urban battle in recent history.

But still, as the film shows, the citizens of Marawi found a reason to smile. Even the young narrator Aminodin manages to exude joy and whimsy despite being surrounded by filth and decay everyday. The child is only seen cracking jokes among his friends, happily mimicking TV commercials and reveling in the curiosities he discovers at the dumpsites where he works. “My father says you must always smile because happy people live longer,” he says at the beginning.

But in the era of It’s Okay to Not Be Okay, many won’t be able to see anything good out of this scenario. This same energy surfaced a few years ago when, after Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque said that he was happy that only 45 percent of Filipinos were unemployed after COVID forced stringent lockdown measures to be put in place. He was “surprised at our resilience,” he said then.

That deference for politeness and resiliency can be occasionally viewed (and tagged by concerned citizens and armchair warriors alike) as toxic positivity. “Filipinos may maintain a positive outlook and find reasons to smile despite difficulties like hunger or natural disasters,” Villa explains. “Foreign nationals who are unfamiliar with the underlying causes of this behavior may find it puzzling.”

But many of our own people have pushed back at the idea of glamorizing hardships instead of demanding better leadership. As Frankie Pangilinan, the outspoken daughter of Senator Kiko Pangilinan, points out: “The over-romanticization of adaptability and resilience is supposed to make us okay with repeated abuse.”

For others

Since we belong to a “collectivist” country, Villa also points out that we rely mostly upon our kapwa (the Filipino sense of shared identity and of others), be it family friends neighbors, and even strangers. “Having the thought that whatever happens there would be someone to help us go through the pain is actually a great reason for many Filipinos to smile in the face of adversity,” she says.

Villa points out that this is a result of cultural values like reliance on the community and the conviction that they will always have someone to care for and support them. “The connections the Filipino people have and the understanding that they are not struggling alone give them strength,” she says. “They have hope and the capacity to keep a positive outlook despite adversity thanks to this support system.”

Kapwa, she continues, is crucial when discussing politeness and resiliency: “The feelings of other people and the effects of one’s actions are factors that Filipinos place high value on. This may result in circumstances where they choose politeness even when they risk being taken advantage of. Being overly accommodating or tolerating unfair treatment are occasionally consequences of the tendency to put others before oneself.”

Sta. Maria adds that interpersonal relations seek to develop the good kasama [companion], kaibigan [friend], and kapatid [sibling]. “To be a fine comrade requires mastering the art of smiling and understanding there is a difference between kangitian, a person with whom one is merely exchanging smiles in greeting, and nakuha sa ngiti, getting what one wants by using a smile,” she says. “The smile is powerful diplomacy.” The writer shares an Ilocano proverb: Ti isem saan nga gatgatangen, Ngem makaparnuay ragsak ken ginawa. Or, a smile is not bought, but it creates joy and well-being.

Villa however stresses that the potential drawbacks of being overly polite in this situation must be understood. Being polite and resilient might be perceived as admirable, but they should not be a tool for exploitation nor sacrifice a person’s well-being.

“For personal development and empowerment, it’s important to strike a balance between upholding positive attitudes and standing up for one’s rights,” the psychologist says. “As cliché as it may sound, self-care must come first. We can better care for others if we take care of ourselves. We need to know when to be gracious and resolute, as well as when to speak up, make our needs known, and stand up for our rights. Never should being polite entail tolerating abuse or holding back our true feelings and desires.”

Striking this balance, she continues, creates boundaries that shield us from exploitation, strengthen our sense of self, and protect our mental and emotional well-being. “It’s essential to keep a positive attitude while also speaking up for ourselves, establishing boundaries, and resisting any kind of exploitation or injustice,” she says. “Keep in mind that by caring for ourselves, we are better able to care for others.”

In her years of practice, Villa has found Filipinos to be highly motivated and inspired greatly by their families, with their actions and aspirations helping their kin to be better as a whole. “Every factor that we have as a person is directly connected to our family. When you ask a Filipino what the reason is that he/she is working you will almost get the same answer ‘Para sa pamilya ko’.”

In ancient, pre-colonial times, motivations for smiling seemed more centered on the self. In 1617, Sta. Maria adds, Mateo Sanchez noted the Visayan mananusad who specialized in decorating teeth with gold inlays, pegs, and caps. “Examples are on display at Ayala Museum in Makati,” she says. “The gold ornaments would glimmer and glitter in the sunlight when one smiled, just like heroes of epics such as the Manobo Ulahingan. A golden smile made a mortal appear mythic.”

Achieving “mythic” status might not be the concern of many today. These days, the other is more emphasized. That is to say, as with many Filipino values and concepts, our smile is layered in its unique and healing duality; it is inherently individual and collective. Like kapwa, hiya, respeto, tuwa, it is both the one and the whole, the citizen and the community, my niece’s and a grieving city’s, yours and ours.