In Batanes, “a microcosm of a sustainable world,” we find our people’s beginnings—a story of earth, sky, craft, and boundaries broken.

A storm was gathering. Or some form of inclement weather—it’s hard to be certain in these times. It was June, a month on the cusp of what is the traditional typhoon season in the Philippines, and we were on a rocky promontory in Batanes, the northernmost province of the country, on an island that lies right on the exit path of the region’s typhoon track. As the first droplets fell, the crew took shelter and Sharif Hamza, our photographer, instructed everyone to stand down. There would be no pictures here.

As I write this, Batanes has just been whipped by Typhoon Egay (Doksuri) as it made its way out of the PAR toward China. The usual calls for relief goods have been made for nearby provinces Cagayan and Ilocos Norte, but the sea journey to Batanes will be unnavigable, and small aircraft most certainly won’t be able to land until the last gusts have dissipated.

Batanes has always been isolated from the main Philippine island of Luzon. Like the Iron Islands of Westeriosi lore, Batanes is set apart, adrift, its small rocky isles swept up by gale force winds over millennia. The people of Batanes, known as the Ivatan, are necessarily hardier, possessing a fortitude that transcends resiliency. They have survived typhoon after typhoon, with rarely any casualties, because they are prepared, and have always been.

This is the group of islands that Vogue Philippines chose as the location for its first anniversary cover story. Often compared to Scotland or New Zealand, the hilly green terrain is a foil to the prolific tropical imagery of Philippine beaches. But Batanes is truly unique, and not just for the scenery.

Before I left on the flight from Manila to Basco (delayed by two days due to a weather hiccup), I spoke with the independent curator Marian Pastor Roces, who co-authored an entire book on Batanes, titled A Delicate Balance: Batanes Food, Ecology, and Community (from which I derive much of my information). She expressed that she wanted to convey the sense of awesomeness of the place. “I’m not inclined to use the word awesome, but if you want to see your past, it’s in Batanes,” she said. “It’s a special place, but not because it’s different from you and me. It’s because you will kind of see something of yourself that you lost.”

With those rather mysterious words, I prepared myself to look at Batanes in a different way, although I didn’t know what to expect. I first visited the islands 14 years ago on a media trip where the organizers upped the ante by creating a sort of heritage trail “Amazing Race” for us to take part in. The challenges were all related to Ivatan culture: the cogon relay race, for instance, required us to run with huge bundles of the dry grass, representing the community effort it took to build the thatched roof limestone houses of Batanes. At Valugan Bay, popularly called Boulder Beach, teams had to quickly arrange stones in the shape of a tataya, the local boat, approximating the seaward burial markers that the ancient Ivatan created over the graves of their dead. Being seafarers, the Ivatan would naturally expect to be sent to the afterlife in a boat.

What I didn’t know then was that the Ivatan are not just any indigenous group in the Philippines—they are in fact the first settlers. Around 4,000 years ago, groups of people from the island now called Taiwan sailed southward in small boats, landing in Itbayat, the largest island of Batanes. Their spread didn’t end there, and they continued to travel to other nearby isles and toward Luzon, then outward, settling all of Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands to the east, and Borneo and Madagascar to the west. The Maori of New Zealand were among their most recent progeny, establishing themselves only 800 years ago.

These migratory people, linked through commonalities in language and other shared cultural characteristics, are called the Austronesians, and their expansion around this half of the world is considered the second greatest dispersal of humans since the movement out of Africa over 100,000 years ago. (So to the recurring question, are Filipinos considered Asians or Pacific Islanders? The answer is: yes).

This is the awesomeness to which Pastor Roces refers: “Nearly all of today’s Filipinos, Malaysians, Indonesians, Polynesians, and a significant majority of the people of Madagascar share one parent stock,” she writes in A Delicate Balance. “The descendants of the Ivatan are now more than an astounding 400,000,000 people.”

It can be supposed that the Ivatan that emerged from the first landfall of the Austronesians were the first Filipinos. And they’re still here.

Whatever the Weather

The gray clouds turned out to be just a passing afternoon shower, and Sharif restarted the shoot, locating a grassy highland with the ever-present Mt. Iraya, mother mountain of Batanes, hovering in the background. The cows were grazing lazily, which made me remember something a Batanes tourism officer told me those many years ago, explaining why nobody here dies in a typhoon. “People here can read signs—they look at the changing color of the sky, they track the movements of the cows,” he said. Apparently, If the cows start heading to the lowlands, that’s a sure sign that a typhoon is coming in two days. Horses don’t fare as well, staying on the hilltops and getting blown away when the typhoon hits.

In a community of generational fishers, Ivatan knowledge of the weather is a deeply rooted skill. They read the shape of the clouds, the movement of the waves, the face of the moon. Anyín, or the storm, is the fiercest creature the Ivatan will ever encounter. The wind itself has at least seven different names, depending on whence it blows; the sea, also, is not just the sea, but is madinak when it is calm, mabkas when the waves are big, and so on. The Ivatan cannot tame the wind just as one cannot conquer the sea, so they build thick stone houses that withstand the strongest anyín and craft compact row boats that pitch and roll with the waves.

Batanes is surrounded by water, with the Pacific Ocean to the east and the West Philippine Sea to the west. The Bashi Channel, the waterway separating Taiwan from Batanes, and currently a geopolitical flashpoint in China-Taiwan relations—has appeared in the greatest book of the sea ever written, Moby Dick. “When gliding by the Bashee isles we emerged at last upon the great South Sea… that serene ocean rolled eastward from me a thousand leagues of blue,” waxes Ishmael the sailor. Though they didn’t anchor in Batanes, Captain Ahab passingly sniffed the “sugary musk” emanating from the isles, a reference, no doubt, to the sugarcane wine called palek (basi elsewhere), widely imbibed by the locals during rituals and ceremonies, as well as the ceremony of daily life.

Beyond Boundaries

Our cover models got to know one another over the course of several meals shared in the dining hall of Fundacion Pacita, a hilltop lodge that was once the home studio of Batanes-born artist Pacita Abad. The dining room’s big blue picture windows frame the startling view outside: hedgerows neatly segregating sloping plots of land, cows teetering at very steep angles, and the vast ocean beyond. Every glance out the window was disorienting. Am I really in this place?

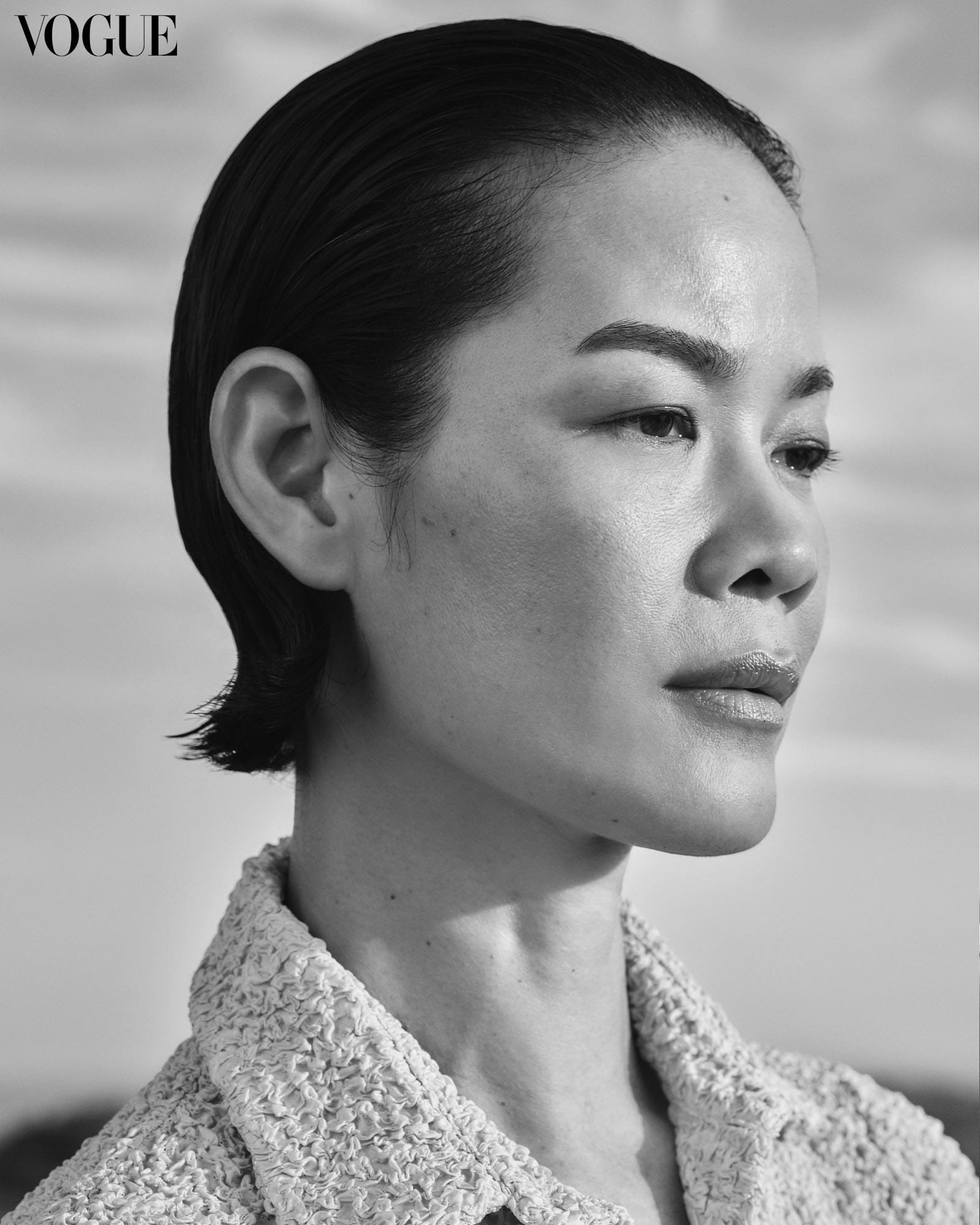

We were graced with Jo Ann Bitagcol, a veteran of the fashion industry, photographer and creative director of her own clothing label; Rina Fukushi, a Japanese-Filipino model; and Lukresia, a queer model and designer from Cebu who went viral for serving couture made out of scrap fabric, plastic wrap, and whatever else she could find in her chicken-filled backyard.

Jo Ann’s story is well known in the local industry—she was scouted at a panciteria in Bulacan, right after she had quit her job at a factory and right before she was about to apply for work at a fast-food chain. After years of modeling, she noticed some bad images in her folio, and thought about taking her own pictures. “My being critical about myself led me to photography,” Jo Ann says. Then came the scarves, which were printed with photos of antique vanity sets and baro’t saya, outtakes from Fashionable Filipinas, a book she worked on with Gino Gonzalez and Mark Higgins. She recently launched a new collection of wearable art pieces with images of hair combs and other vintage accessories assembled to form human figures.

“I’ve always wanted to go to Batanes. I never thought I’d get the chance to [in my modeling days], so this is a dream come true.” Jo Ann says. “With the integration of culture in my photography, our heritage and our roots come back to life. My experience [in Batanes] also brought me life, and I think another chapter is beginning to unfold for me.”

The 24-year-old Manila-born Rina started making waves when she was just 17 and already gracing the catwalks of Bottega Veneta, Chloe, and Miu Miu. Her journey to top modelhood wasn’t without its hurdles, however, since being hafu (of mixed ethnicity) wasn’t always perceived to be the ideal, especially growing up. Then she was scouted in Harajuku, at the age of 14.

“I was bullied a bit at the time. I didn’t think my appearance was particularly different from everyone else, but [with a Filipino mother and mixed-race father] my face doesn’t look so Japanese,” Rina says. “But all the things I was bullied about were affirmed when I started modeling. I was told, ‘That’s your identity,’ ‘That’s your individuality,’ and that gave me confidence in myself. It was hard…but it made me stronger and made me realize that it’s okay to be different from others.”

Rina admits that when she first heard that Batanes might not have any internet, she felt a little nervous. “However, once I arrived in Batanes and spent a few days shooting with everyone, I was warmed by the love and affection of the people and the peaceful and natural atmosphere of the island,” she says. “It was a fashion shoot that I would not normally be able to do, capturing my inner self—with expressions that came from within.”

Lukresia, also known as “thirdworldbb,” was “discovered” on Instagram by the team of Mugler, who invited her to take part in the label’s spring/summer 2022 film. Visa issues prevented her from leaving for the first, second, and third time. Finally, on the fourth invite, Lukresia took off to Paris and triumphantly sashayed for Mugler’s return to the runway, sharing the stage with such names as Eva Herzigova, Shalom Harlow, and Amber Valletta. No Filipino since Anna Bayle has walked for Thierry Mugler since the ’80s and ’90s—and Lukresia is the first queer Filipino to do so.

She says of her Batanes experience, “Everything just felt symbiotic. In Batanes, it’s like working with nature. You have to surrender to the elements.” Surrender they did—on the last day of shooting, as they were chasing the sunset, a swarm of gnats suddenly flew in and enveloped everyone. “We could’ve gone on for two more hours, but nature was telling us we had to stop. It was time to wrap up.”

Taking Root

On the menu for breakfast: flysilog. It’s the Batanes version of the traditional Filipino breakfast of garlic rice, egg, and fried bangus, but here the freshest catch is dibang. Flying fish can be seen skipping all over the waters around the islands, so it’s no surprise they would land on our plates. More than a staple, the flying fish is an integral part of the community-defining activity that happens during the arayu fishing season, when the golden dorado enters the coastal waters in the summer months from March to May.

Our tour guide Kuya Arnel, the son of a mataw fisherman, described how in early March, a group of hook-and-line fishermen would gather on the beach for the mayvanuvanua ceremony. A shaman would read the entrails of a slaughtered pig for signs of the coming fishing season when palek is drunk, offerings are made to the sea, and prayers are recited for an abundance of catch and protection from harm. The fishermen first set off to catch flying fish, which are kept as live bait for the main hunt, or rather summoning, of the arayu—variously called dorado, dolphinfish, or mahi-mahi, depending on what sea it swims through.

At the end of the season, all of the arayu, which have been dried and smoked, are sectioned off and distributed to the community members. The provisions are meant to last families for an entire year, and only the leftovers are allowed to be sold. This is the Ivatan practice of sustainable fishing, and it is something they have been doing ever since the Ivatan can remember. When it’s not fishing season, they focus on growing tubers and root crop, less prone to destruction by typhoons.

Looking across the ancestral domain of the Ivatan—all the islands of Batanes and their surrounding wild waters—I thought I was beginning to understand what Marian Pastor Roces was saying. I could see what we, as a Filipino people, have lost. Batanes is a microcosm of a sustainable world, where people farm organically and regeneratively and fish for only what they need. They are guided by an ethos called atatayin which is a kind of communal sharing and reciprocity. As Pastor Roces writes, “Batanes atatayin wisdom is neither charity nor patronage… it is a system for guaranteeing dignity, where no man or woman is allowed more—or—less—than what was contributed by he or she.”

Children of the Craft

The global fashion industry has begun to reckon with its impact on the planet, a realization crystallized in that staggering image of a mountain range of discarded clothing—mostly unused fast fashion—in the Atacama Desert.

Vogue Philippines went to Batanes to shoot high fashion in the highlands, its vistas setting the scene of the story we want to tell, one that celebrates the work of our hands.

Filipino designers, due to scarcity, have always been resourceful when it comes to making things. We’re at a moment when the type of ingenuity that Filipinos have always possessed is being celebrated because it aligns with current values of circularity and sustainability. At the same time, the Philippines also claims an age-old heritage of weaving and traditional craft, using the raw materials of nature like abaca, rattan, and pineapple, even those that are considered invasive, like the water hyacinth. This, too, is part of our DNA.

This fashion story assembles several Filipino designers from a range of styles and specializations and puts them on equal footing with international names. “The upcycling and the artisanal, honing in on local craftsmanship, looking at young Filipino designers and what they can achieve… we also shot a lot of Parsons designers, and we had pieces from big brands like Sacai and Marc Jacobs and Rick Owens,” says stylist Melissa Levy about the production. “So it was incredible to see a harmony amongst all these levels of fashion, and then with the diversity in casting and all the different expressions of what it means to be Filipino.”

Patricia Perez Eustaquio, an artist and designer who moved from Manila to the north of Luzon, fabricated an outfit made of jute sacks inspired by the people of the Cordilleras. “Upcycling is integral to their lives and a deeply ingrained mindset in this farming, mountainous region,” she says. Using jute sacks that are resold at the Baguio market, Patricia stitched them with retaso (offcuts), t’nalak end cuts, and other old fabrics, then added embellishments of dyed green tiger grass, the kind used for making brooms.

Jerome Lorico, whose twisted knit dress took hundreds of hours to complete, says that he searched hard for a local yarn supplier to get the right rustic and natural texture that reflects the tactile quality of Ivatan utilitarian products. A vintage hand-guided knitting machine knitted the fabric, but the pieces were hand-sewn together using a difficult technique called surface and tension draping. “I find it meditative to work on something that is intensive but carries with it an element of peace and unity,” he says.

The handwoven basahan-inspired look by Leby Le Moria is credited to her high school classmate, whose family ran a rag-making operation in their home. “Resourcefulness is one of the core languages of Filipino design and the basahan is one of its products,” she says. “As someone who has been an admirer of the beauty of basahan, I believe that it can be in other form—that it can be used other than keeping footwear and floors clean.”

Designer Neric Beltran, who dresses stars like Anne Curtis and Heart Evangelista, in high-wattage outfits, constructed a piece out of recycled water bottles, each garland a string of black phalaenopsis orchids. “We make use of what’s available and are able to create beautiful work within the limitations,” he says. “Even if we are not technologically advanced, we still create, with our hands, with our will, and with our passion.”

These are just some of the stories behind the craftwork that fills these pages—each designer and

collaborator has their own tale to tell. What is shared among them is the understanding that creativity

and inspiration can be found in the most unexpected places, and that strength and perseverance is shaped

by fire and rough seas. In Batanes, we saw something of ourselves that we lost—our deep connection to nature, our spiritual kinship with one another, or perhaps all of the above: a way of living that gives to the world as much as it takes from it.

By Ticia Almazan. Photographs by Sharif Hamza. Fashion Director: Pam Quiñones. Styling: Melissa Levy. Makeup: Gery Peñaso. Hair: Mong Amado. Models: Jo Ann Bitagcol, Lukresia, Rina Fukushi. Nails: New Lounge PH. Art Director: Jann Pascua. Producer: Anz Hizon. Production Assistants: Bianca Zaragoza, Patricia Co. Photographer’s Assistants: Choi Narciso, JV Rabano, Tim Hoffman. Stylist’s Assistants: Neil De Guzman, Renee De Guzman. Makeup Assistant: Ejjay Salcedo. Hair Assistant: Jeremi Nuqui. Intern: Sophia Lanawan. Shot on location at Fundacion Pacita. Special thanks to Patsy Abad and the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples.