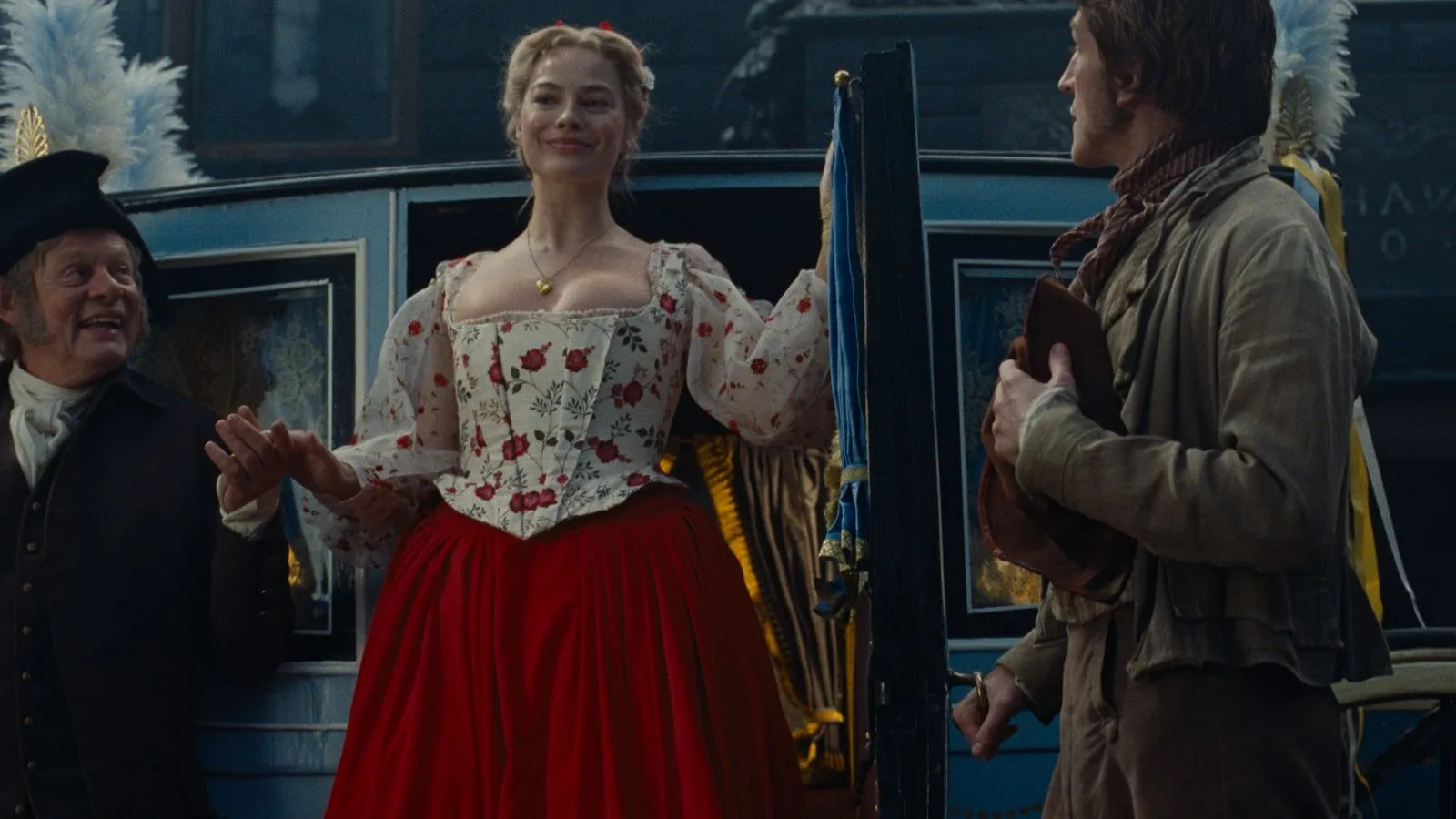

Photo Courtesy Warner Bros. Pictures.

For the past year and a half, the world has been breathlessly discussing and debating Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights – and now, following an endless stream of premieres, interviews and method dressing, the film will finally be in cinemas. After all that, how could it possibly live up to the deafening hype? The delightful thing, though, is that it does – whatever you make of this big, bold, gaudy, controversial melodrama, it is, at least, every bit as maddeningly ambitious and divisive as the promotional campaign that’s preceded it.

It opens with a rapid breathing which sounds like masturbation, but is actually asphyxiation – a young Cathy Earnshaw (Charlotte Mellington) and her only slightly older housekeeper, Nelly (Vy Nguyen), are at a public hanging, watching a man gasping for air. There are bodily fluids, jeering crowds and demonic Punch and Judy puppets applauding through the chaos, giving the scene the air of a demented fairy tale. This was a sequence which shocked many viewers in the film’s earliest test screenings, and it serves as the perfect litmus test for what you’ll make of everything that follows – love it, as I did, and you’ll find much to enjoy in the next two or so hours; loath it, as many seemed to in the screening I attended (there were a handful of walkouts), and it may prove to be a difficult sit.

As should be apparent from this opening, fans of Emily Brontë’s beloved novel would be wise to leave their expectations at the door – this wild take on the classic is, to put it generously, a very loose adaptation of its source material. Its structure is altered, key characters are significantly changed or missing entirely, and countless liberties are taken with the central relationship between Cathy and Heathcliff. (Fennell has been open about such changes, describing the film as being based on her memories of reading the book as a teen, rather than strictly faithful.) But, if you can look past that, it’s quite the ride.

After this head-spinning sequence, Cathy and Nelly skip home past a river of blood to Wuthering Heights, their ominous, coal-stained, other-worldly abode, and soon meet Heathcliff (Adolescence’s Owen Cooper), a young boy whom Cathy’s frequently drunken and erratic father (Martin Clunes) has brought home. Heathcliff drives a wedge between the two girls, with Cathy infatuated with her new playmate. They grow up almost as siblings and, before you know it, morph into Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi.

Trouble begins brewing with the arrival of their nouveau riche neighbours, Edgar Linton (Shazad Latif) and his ward, Isabella (Alison Oliver). Enchanted by their glittering wealth, Cathy enters their world and then returns to hers with newly-acquired airs and graces which infuriate Heathcliff. There’s an undeniable, elemental connection between our two star-crossed lovers, but Cathy also understands what she must do to secure her future.

Then, there’s a period of separation, followed by Heathcliff’s return, having made his own fortune. The heat remains between Cathy and Heathcliff, and this unshakeable bond ensures their mutual destruction.

For the film’s first hour and a half, Wuthering Heights walks a tonal tight rope – it’s bruisingly funny in parts, and almost panto-like in its outlandishness. Robbie, who proved her deadpan comedic acting chops in Barbie, is a joy as the flighty, vain, fast-talking Cathy, totally lacking in self-awareness. As for Elordi, his casting has been rightly criticised and the thick Yorkshire accent takes some getting used to, but the actor, currently Oscar nominated for his sensitive turn in Frankenstein, brings a similar quiet, touching vulnerability to Heathcliff. In its subtle gestures and expressions, his performance also connects beautifully with Cooper’s, as his younger iteration, giving us a view of both the brooding, raging man and the lost boy within.

Also deliciously grim and gleeful is Clunes’s take on Mr Earnshaw – all rotting false teeth and deranged cackling – and Oliver’s Isabella is another highlight, a wide-eyed, thoroughly odd, precocious but babyish young woman trapped in her gilded cage, and fully obsessed with Cathy.

That cage, the magical but also eerie Thrushcross Grange is a sight to behold – an epic, retina-searing, sometimes repulsive, consistently jaw-dropping palace, meticulously constructed by production designer Suzie Davies. From Cathy’s bedroom, with padded walls designed to look like her own skin to the cherry-red, lacquered library; fur-lined staircases; icy, damp, silver dining room; and airless manicured garden, it’s an astonishing achievement and deserves serious awards consideration come 2027.

So does Jacqueline Durran for her ostentatious, already-picked-apart costuming – Cathy’s wardrobe is bonkers, yes, but also exquisitely detailed and thrillingly playful, a parade of showstopping gowns which somehow make you swoon while also making your skin crawl.

Add to this Linus Sandgren’s ravishing cinematography, capturing the blustery moors in all their glory; Siân Miller’s bejewelled make-up work; Charli xcx’s sweeping original songs (often hilariously on-the-nose in their lyrics); and the false, theatrical, hand-painted soundstage feel of everything, and I was floored. Just over halfway into the film, I was nearly ready to declare it a masterpiece – the kind of visually dazzling (and admittedly polarising) confection you could see the BFI showcasing in a decade as part of a series like their recent Too Much: Melodrama on Film. (There’s a Christmas sequence which feels especially ripe for this, complete with endless snowfall and Cathy in a giant Russian hat.)

But then, it doesn’t quite stick the landing. After Cathy and Heathcliff’s many years of pining for each other, when something does finally happen between them, it’s fun, but also somewhat anticlimactic. Their intimate scenes are romantic, sure, but not quite as provocative as what you’d expect from the director of Saltburn. As a result, this portion of the film feels baggier and, after that, for the final hour, Wuthering Heights tips over from campy farce into full-blown, weepy tragedy.

This shift will work for many – there were reports of people bawling at the LA premiere – but others, like me, may be left frustrated with the more lethargic pace, the muddled and sometimes repetitive plotting, and the film’s sudden need for you to care deeply for characters who were previously emotionally distanced and almost caricaturish, and enjoyably so.

Spare a thought, too, for Hong Chau as the older Nelly, who cuts a cryptic, severe, Mrs Danvers-esque figure, and Latif, who brings a soft, gentle tenderness to Edgar, but both are, sadly, under-written and underused. I look forward to the next adaptation of Wuthering Heights which, I hope, will centre on a non-white Heathcliff, and maybe even feature other fully fleshed-out non-white characters.

This Wuthering Heights, in its entirety, is a mixed bag which will provoke a barrage of Op-Eds, and as much outrage as adulation. But it’s also a film which feels seared into my brain – the eye-popping excess, the unbridled, tongue-in-cheek nastiness, the sheer scale and imagination of it all. See it on the biggest screen possible with as many friends as possible, and get ready to argue for hours afterwards.

Wuthering Heights is in cinemas from February 13.

This article was originally published on Vogue.com.

- What Reading Wuthering Heights Taught Me About My Parents’ Marriage

- Margot Robbie’s Chanel Wuthering Heights Dress Was Inspired by the Red Carpet Itself

- Red Latex and New Charli XCX: See the Bonkers Second Trailer for Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights

- Margot Robbie Brings Vintage Galliano to New (Wuthering) Heights