“Any opportunity that I get to re-champion our Filipino culture is really valuable to me.” Photographed by Mark Alvarez

Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods is reborn in Filipino cadence, where Raven Ong and Rajo Laurel’s costumes transform Lea Salonga and cast into figures clothed in folklore, pageantry, and the textures of tradition.

At Manila’s Samsung Theater, Theatre Group Asia’s Into the Woods became more than a fairytale forest; it emerged as a mirror of the Philippines itself.

Stephen Sondheim’s much-beloved musical has been staged countless times across the world, often in minimalist productions or stripped-down stagings, but here it became something else entirely: a spectacle that glimmered with the colors of a local tradition, a reimagining where every gown and cloak, every jacket and robe, was infused with history, folklore, and the textures of Filipino identity.

Under the guidance of overall creative director Clint Ramos, with costumes led by Raven Ong and fashion designer Rajo Laurel, and with Ohm David’s set evoking capiz windows, machuca tiles, and bahay kubo silhouettes, the Manila production became a reminder that stories travel, but they also root themselves.

Santacruzan references and Inabel fabrics for the princes colored the pageantry, while Teatrong Mulat puppetry breathed local artistry into the magical creatures. And in the presence of Lea Salonga, stepping into the Witch with all the force of her voice and history, the costumes had to do more than clothe characters; they had to carry the weight of cultural representation.

For Ong, with the help of his main assistant Hershee Tantiado, the journey began in a moment of serendipity. “I basically received an email from Clint Ramos himself asking if I would be interested and available to design the show. And obviously, I immediately said yes.” It was December, a season of anticipation, and what followed was months of ideation, collaboration, fittings, and a process that drew together weavers, stitchers, and makers from across Manila.

But more than logistics, it was an opportunity to ground the show in Filipino aesthetics. “One is that we wanted to be timeless. Of course, these are fairytale characters. We absolutely did not want to lose the fairytale aspect to it…and as much as we did and used a lot of Filipino themes for everything, we still wanted it to have an international appeal. Just because, you know, we have actors and performers who are well known internationally so we still want people even outside of the Philippines to appreciate the themes that we were going for.”

“People really do appreciate [the show]… they felt represented, not just on stage, but as a whole, as a Filipino.”

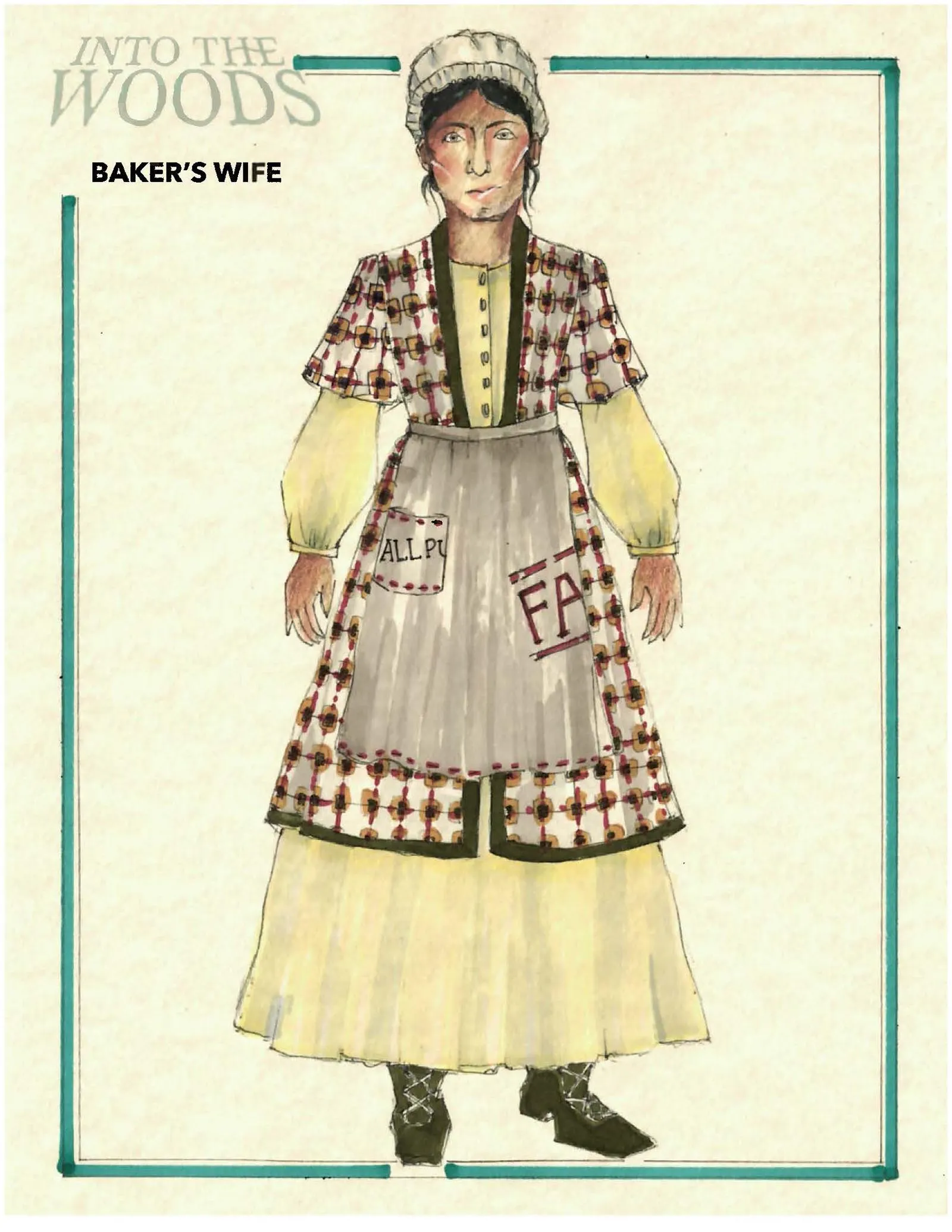

Ong’s vision, however, was not simply decorative. For him, textiles themselves carry the courage and resilience of a people. “The courage of Filipinos really are very much a symbol of our textiles and what we wear. So if you think about the courage that the Baker and the Baker’s Wife had… that really also did serve as a main focal point and inspiration for using the Filipino textiles. Because to me, the symbol used is equivalent to an armor piece.” In every weave and stitch, he saw not just beauty but strength, not just costume but metaphor.

Behind the beauty, there was pressure. “It was just, like, a lot of pressure. It’s a sold-out show. People are expecting so much, with Lea Salonga in it, with international Broadway performers in it. I was nervous, as a designer.” But the reception silenced doubt. “People really do appreciate [the show]… they felt represented, not just on stage, but as a whole, as a Filipino. They’ve had this joy of just seeing a lot of the Filipino touches and the details that we use for the production design of the show.” For Rajo Laurel, the pride was personal. “We consider Lea as our national treasure. So given any opportunity that I can dress her up, I say yes.”

Raven Ong’s path to Into the Woods in Manila was one of both distance and return. After leaving the Philippines in 2014, he earned his Master’s in Costume Design at the University of Connecticut and trained in New York under Eric Winterling, whose Manhattan costume shop is among the largest in the industry. Since then, he has combined professional practice with teaching at Central Connecticut State University, where he is now a tenured Associate Professor of Costume Design. His portfolio spans regional and repertory theater in the U.S, from Sense and Sensibility at Syracuse Stage to Antony and Cleopatra at the Utah Shakespeare Festival, as well as Manila productions like Buruguduy and Jepoy and the Magic Circle. Yet whether in New England classrooms, Utah deserts, or Philippine stages, Ong’s vision is constant: a belief in costumes as carriers of history, identity, and resilience.

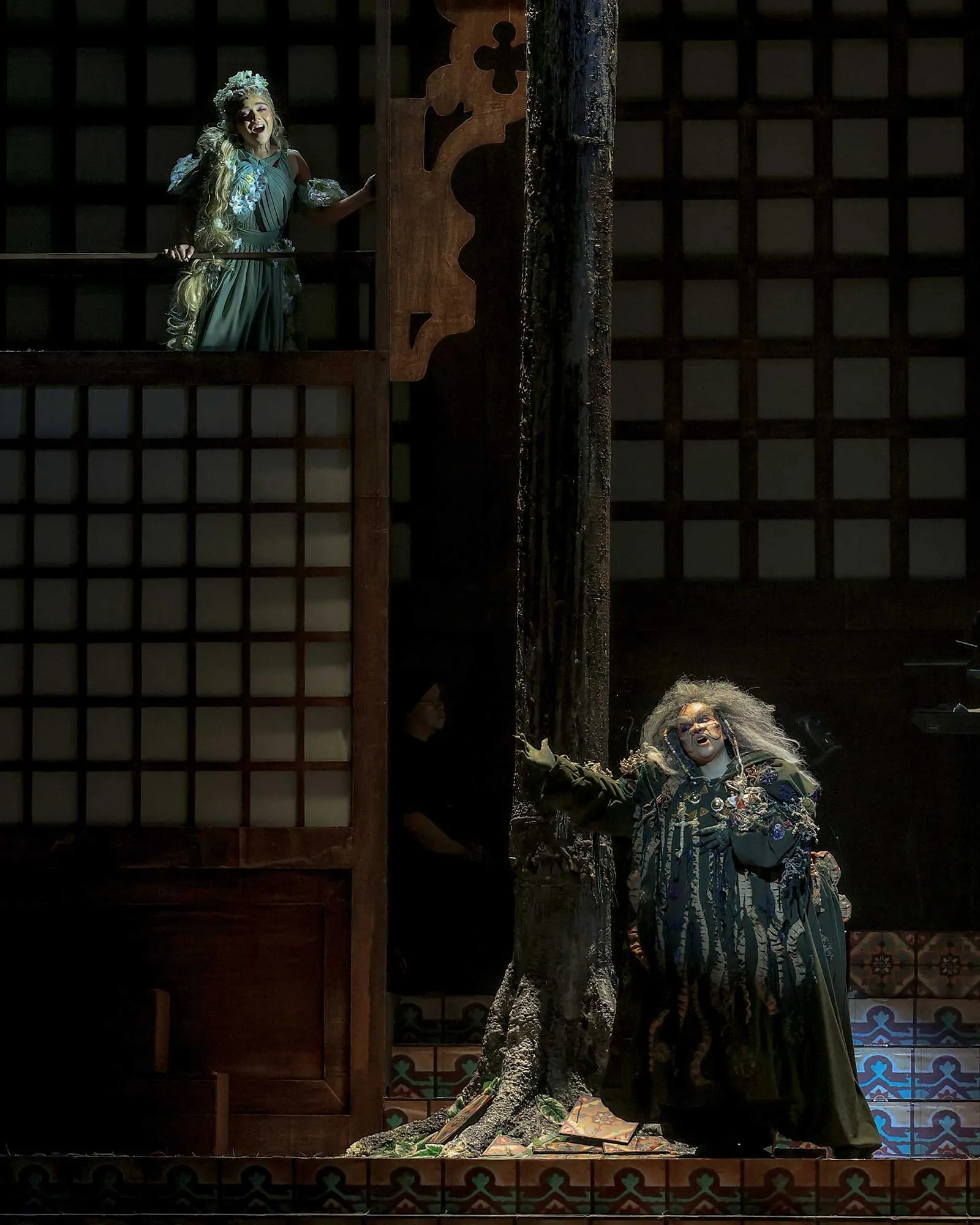

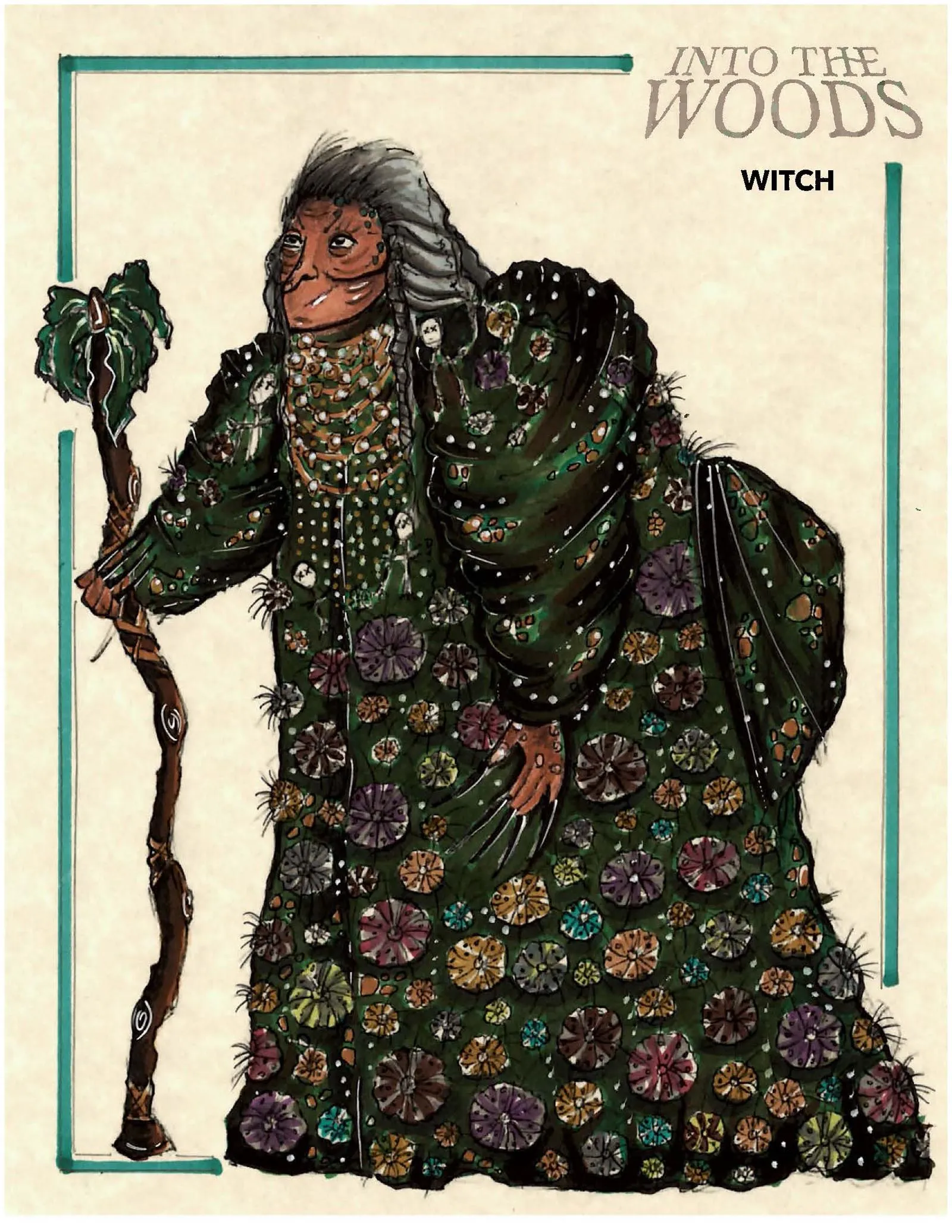

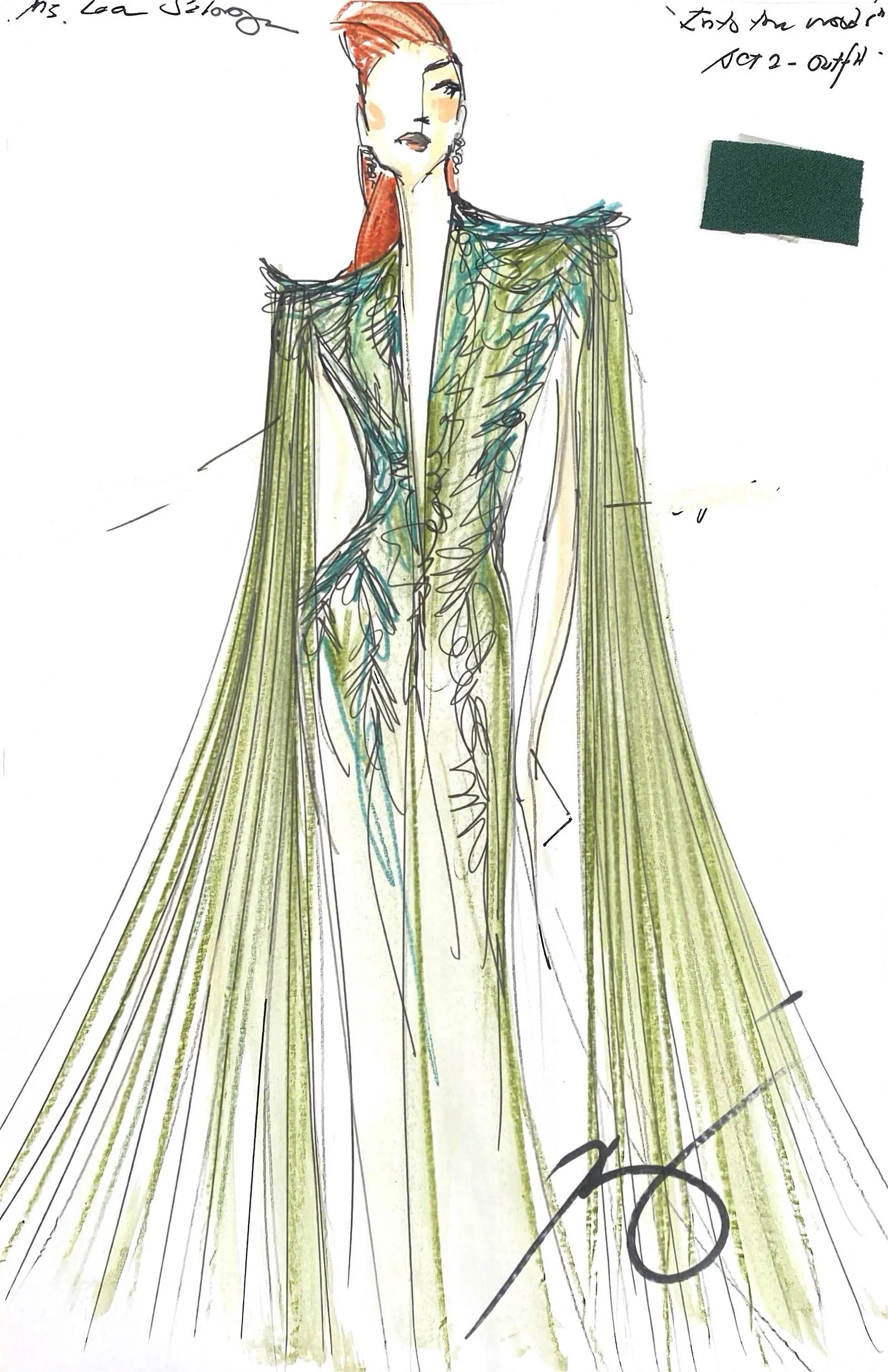

The Witch

No character embodied the Manila production’s fusion of folklore and spectacle more than the Witch, played by Lea Salonga. Here, Ong and Laurel worked in tandem: Ong designed her Old Witch, Laurel handled the transformation and her Act Two looks.

For Ong, the starting point was to locate the Filipino counterpart to a figure so deeply entrenched in Western fairytales. “For the Witch, we really did think about the Mangkukulam, which is our Filipino counterpart of the witch. The Mangkukulam just basically involves some voodoo. We thought that perhaps the use of the talismans or the anting-antings, as we call them, would also be a nice touch because she didn’t want to be cursed anymore. She’s cursed enough that she can’t take any more curses.”

The robe she wore as the Old Witch was heavy, almost oppressive. Ong used fabric manipulation to create deformity, and he borrowed from the history of Western fashion to exaggerate her grotesque form.

“I thought that the leg-of-mutton sleeves of the 1890s piece would be good… just to show bigger arms. And then I also made use of the Victorian bustle too… her butt can be a lot more exaggerated with the use of a Victorian bustle.” The result was a figure whose very shape told of her suffering. The robe had two hemlines, cleverly rigged to allow the magical transformation into Laurel’s gown without revealing a trace of it too early.

Laurel, who has dressed Salonga for more than twenty-five years, understood the intimacy of designing for her. “The beauty about my relationship with Lea is I’ve known her since I was six. We both started as child actors in Repertory Philippines, The King and I. I’ve been making her clothes for more than 25 years. So I actually already know what makes Lea comfortable.” That trust allowed Laurel to push boldly into imagery that was both spectacular and deeply Filipino. For the transformation gown, he turned to nature. “We really wanted to be inspired by this Filipino foliage called anahaw, which if you take a look at it, looks like beautiful large fans. And so essentially we wanted to use these fans as a starting point for the design.” He also looked at the pageantry of Flores de Mayo. “The collar of the Witch was inspired by that. So all of these little elements of Filipino images were culled and we wanted to integrate that into Lea’s costume.”

The gown burst in verdant green, lush and youthful, announcing vitality regained. By Act Two, however, the shade deepened. “The transformation was this very vibrant, very verdant green…and then the second act, when she lost her power, she basically changed into a deeper shade of green, almost like assimilating that she’s aging again to that particular process.” For Laurel, seeing Salonga embody the role was more than design; it was emotional. “Seeing her really at this point in her life with my dress and our costumes with Raven and I sort of left this wonderful feeling of joy, absolute joy, and emotional context…I was weeping at one point.”

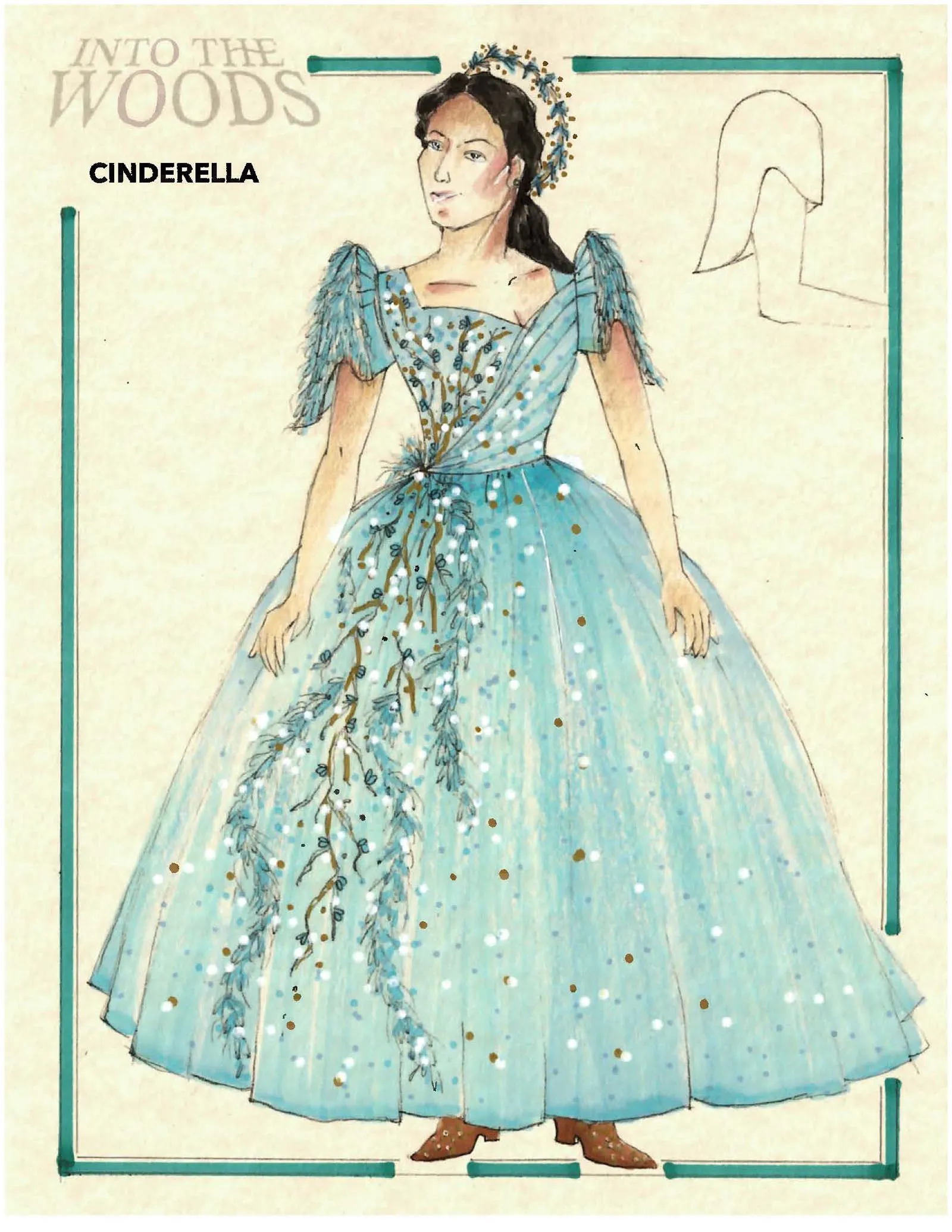

Cinderella

If the Witch was defined by transformation, so too was Cinderella. Ong rooted her in Filipiniana imagery, drawing on Fernando Amorsolo paintings of the terno. “The main inspiration for her really is Amorsolo paintings, like the Balintawak, the Terno version in the country. And so we took a lot of time to look at these images and see how we can stylize and infuse some Filipiniana and western elements combined together.” Her rags bore hints of blue, a foreshadow of destiny. At the ball, her gown unfurled in powder blue with butterfly sleeves reshaped into bird wings, symbolizing her connection to her mother and to the birds who sent her the gown. “The gown technically is from her mother and Cinderella is able to communicate with the birds… I thought that the theme would be butterfly sleeves but then in the shape of bird wings.” Her progression culminated in a deep royal blue as queen.

Cinderella’s mother was reimagined as a Babaylan, a pre-colonial priestess, crowned with a headdress of tree branches, a living spirit of both woman and tree. “I thought that it would be best to represent the mother as the babaylan… more like a pre-colonial priestess.” The Stepmother, meanwhile, was drawn from the character of Doña Victorina from José Rizal’s seminal novel Noli Me Tángere, a satire of social climbing. While the Stepsisters borrowed from Manila Carnival Queens and the flamboyance of Flores de Mayo. “The stepmom basically treats the daughters as like the flowers that she offers the prince… so I thought the visual representation of flowers might be really good for the stepsisters.” Their gowns were camp in the truest sense, floral extravagance paraded like pageantry, their silhouettes echoing the arches of festival carriages. In Act Two, blinded, their silhouettes collapsed into Regency lines, vertical and restrained, as their flamboyance fell away.

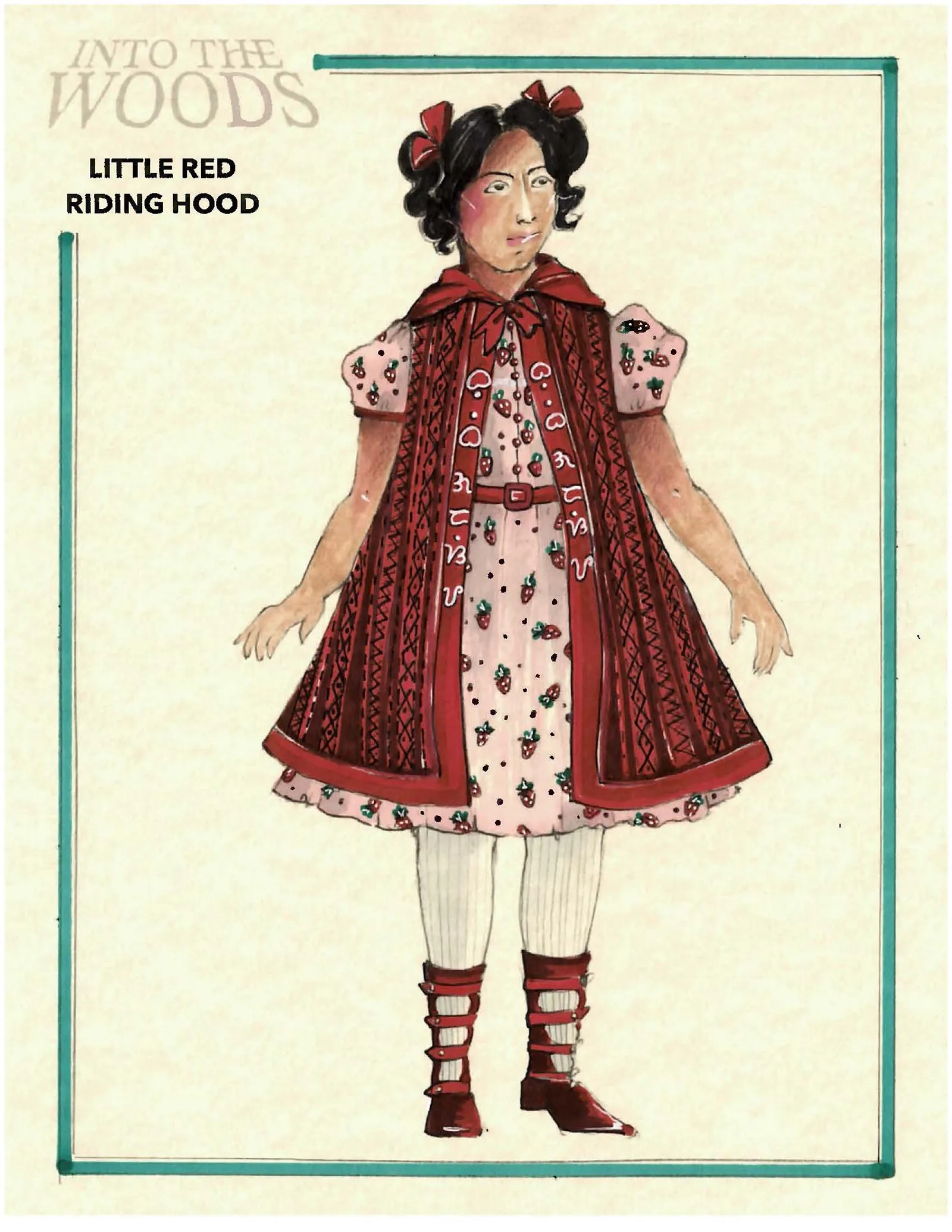

Little Red Riding Hood

Little Red Riding Hood was dressed in Cordillera weaves, the red textiles of the north, her cape embroidered with baybayin spelling the name of the late theatrical producer Bobby Garcia, imagined as a gift from Granny’s hands. Ong’s personal history bled into the design. “So yes, we did use a lot of Cordillera weaves for Little Red’s cape… I thought that, you know, as a designer, a lot of what you see in your design really is based on your experience. A lot of that is you.” He found strawberry-printed fabric as well, tying it to his summers in Baguio, when he picked strawberries in the fields. Costume as autobiography, folded into character.

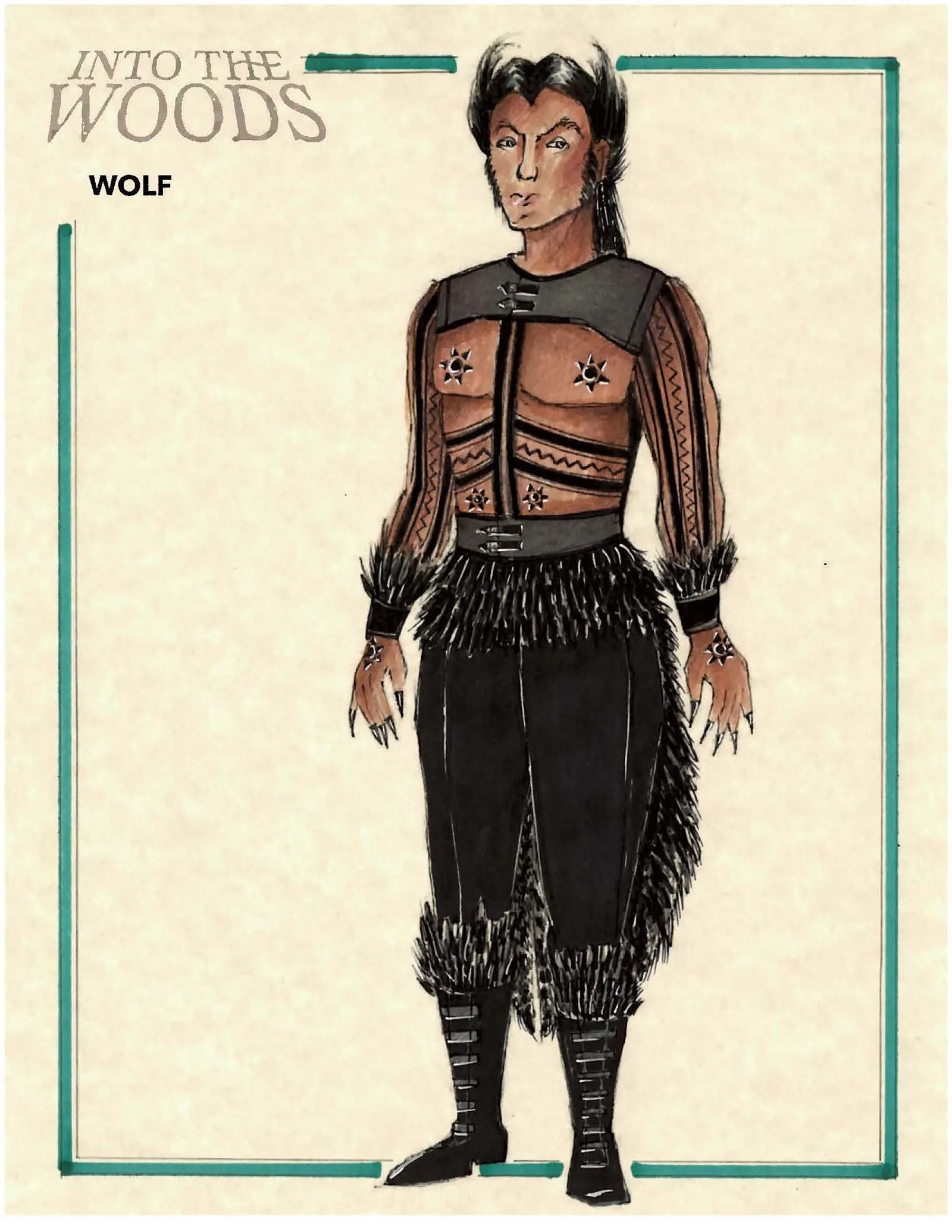

The Wolf

The Wolf prowled the stage in a costume born of the Sarut, the Filipino werewolf. “We actually have a version of a Filipino werewolf in the Philippines, and that’s called the Sarut… so I thought that this might be a good inspiration for the Wolf.” Rejecting cartoonish tails, Ong built him a faux-fur tailcoat, overlaid with tribal tattoos inspired by the Boxer Codex, mixing werewolf with Aswang, predator with seducer.

Rapunzel and the Princes

Rapunzel, innocent and pure, bloomed in sampaguita. “Her inspiration really is the sampaguita, which is still very much Filipino in context. A symbol of innocence, the symbol of purity… she decorated her hair with all of these sampaguitas.” Her braids, styled by Johann De La Fuente, were anchored in abaca, tying her imprisonment to the land itself.

Her prince wore tailored Western jackets but sewn from Maguindanao wool, detailed with gold epaulettes, a blending of romance and heritage. The use of Inabel fabrics stood proud in the princes’ costumes, rooting their royal attire in local weaving traditions while balancing their Western silhouettes.

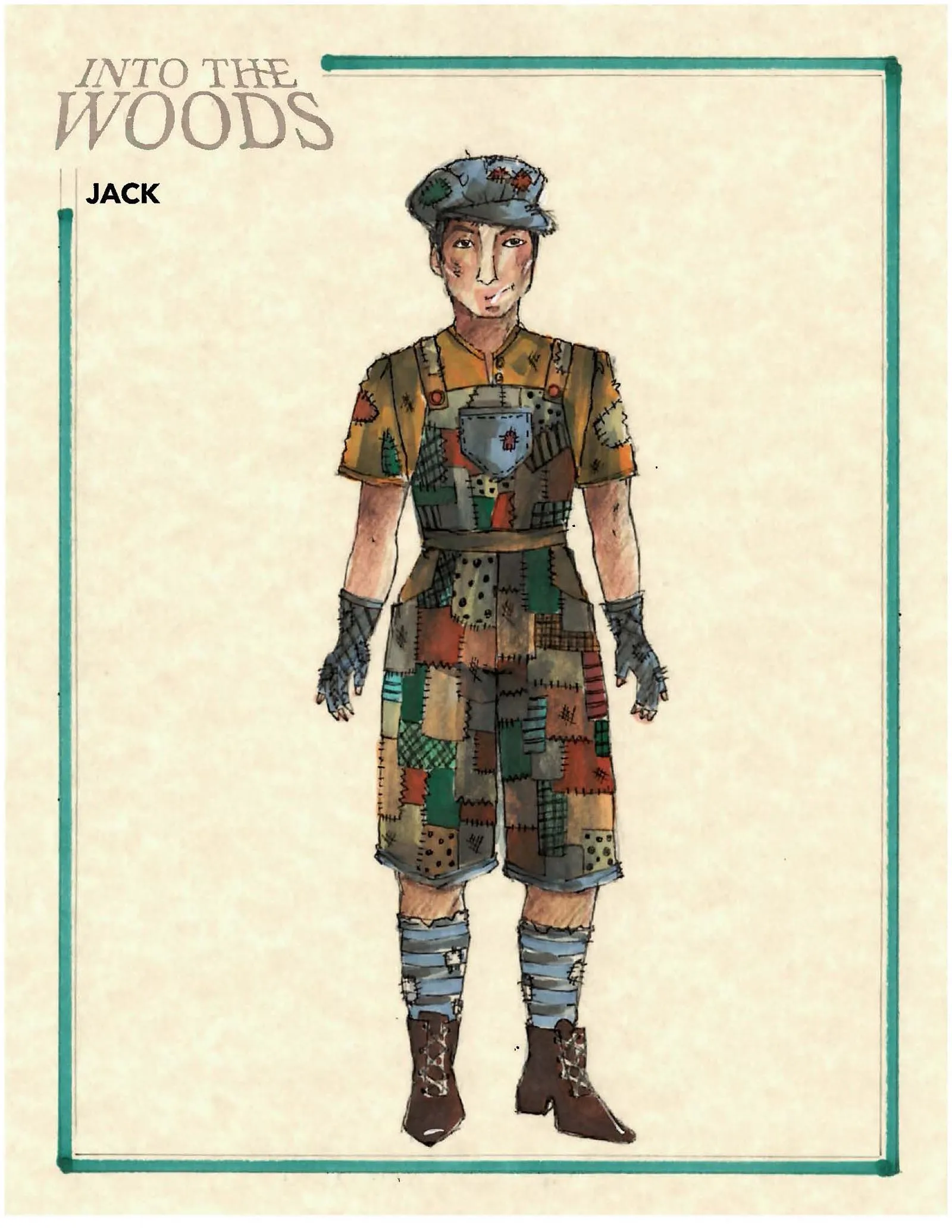

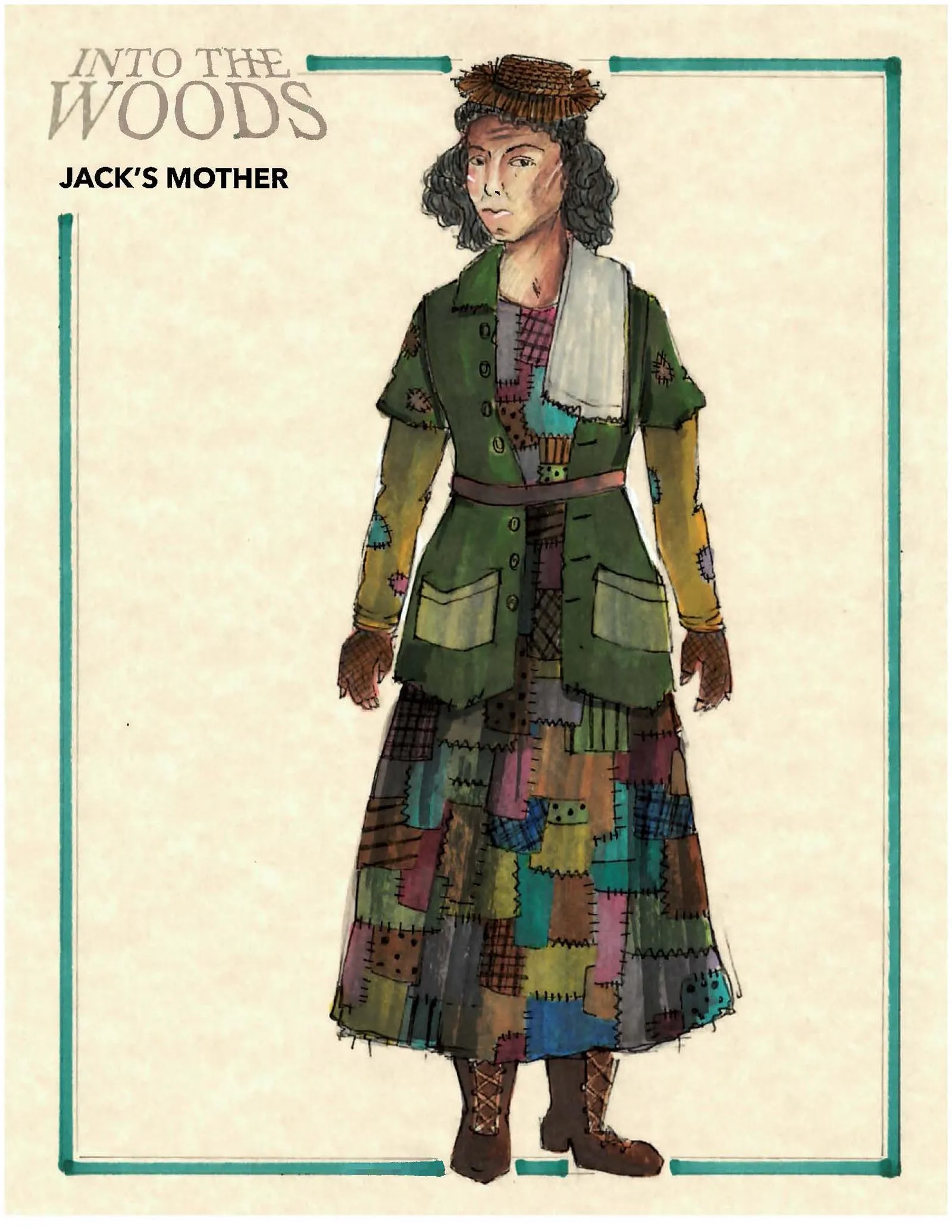

Jack, His Mother, and Milky White

Jack and his mother were stitched in patchwork, a metaphor of resilience. “I wanted to really showcase how hardworking we are as Filipinos… creating something beautiful out of something that’s existing says a lot about us.” Jack’s mother carried a pineapple patch near her heart. “It might be just like a simple patch of a pineapple, but that really means a lot to us.” When wealth came, her garments shifted into the blue of the 1,000 peso bill, embellished with gold jewelry. Jack, too, shed rags for a bowtie.

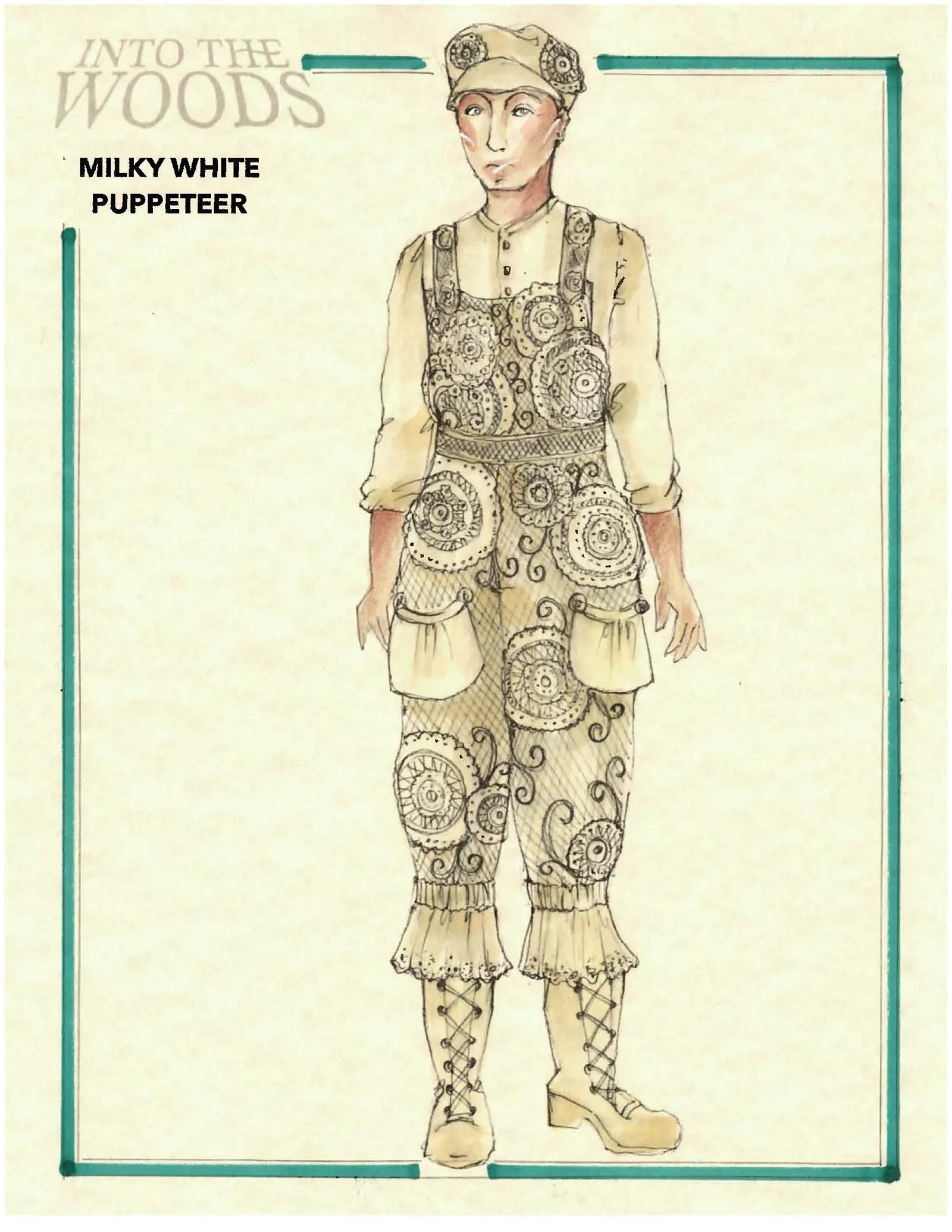

Milky White, his cow, mirrored him in a crocheted jumpsuit. “If I was thinking as the designer, if there’s a human version of Milky White, I designed it so that they’re like twinning.” The crochet evoked grandmotherly hands, handmade love woven into the animal’s very form.

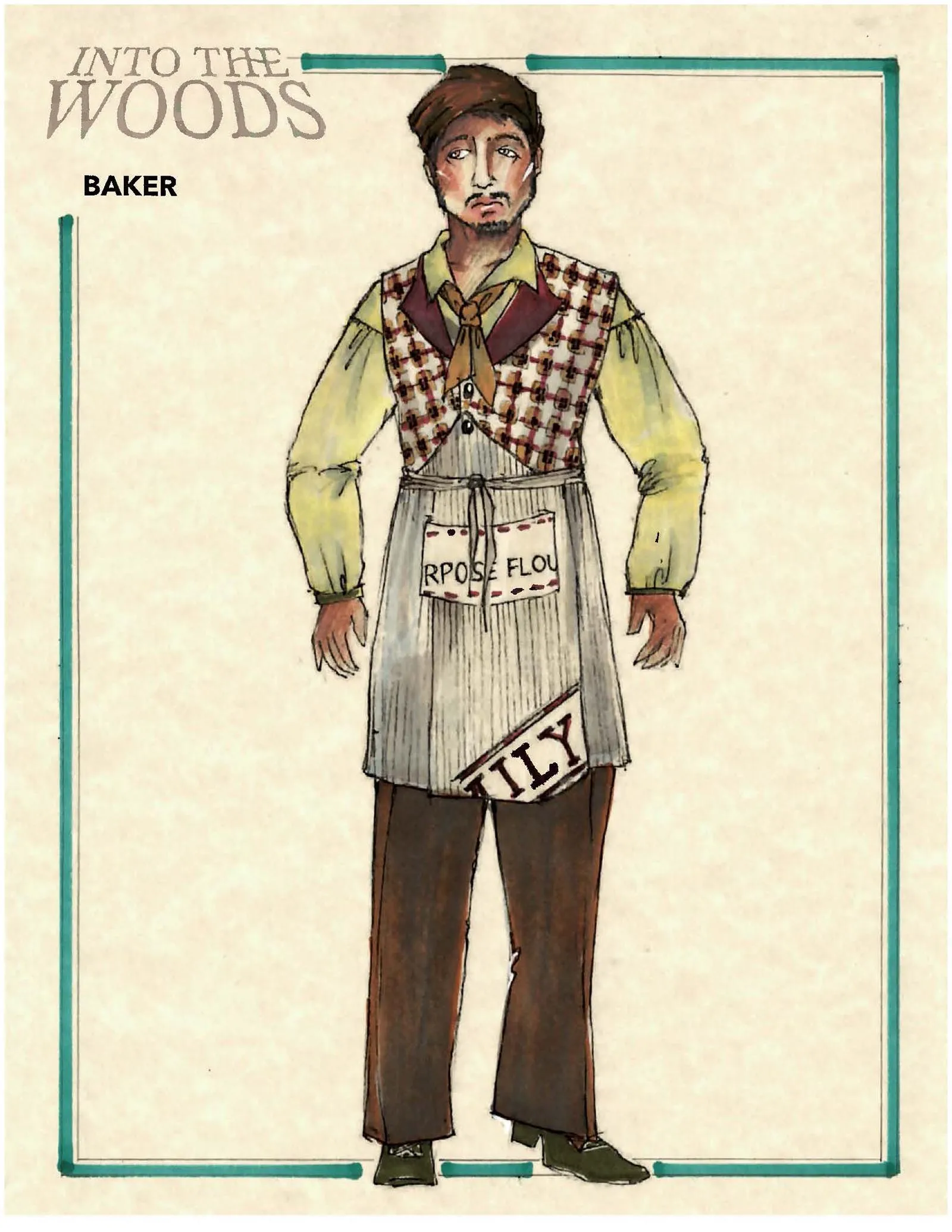

The Baker and His Wife

The Baker and his Wife wore armor of Inabel fabric. “Those pieces really are a symbol of courage for me. The weaving process of these textiles already says a lot about us as Filipinos. That alone is worth showcasing.” Ordinary villagers clad in extraordinary textiles, their costumes proclaimed the heroism of common courage.

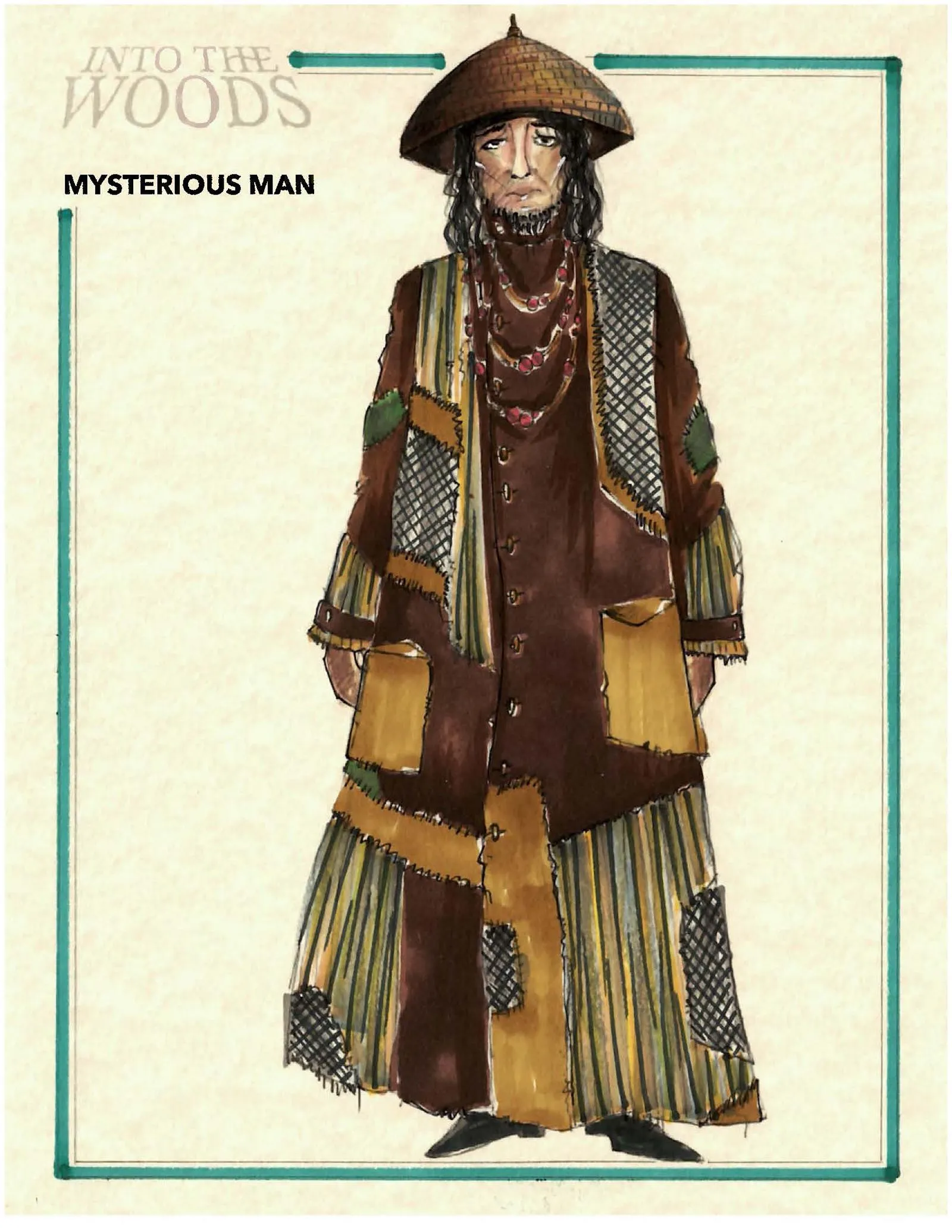

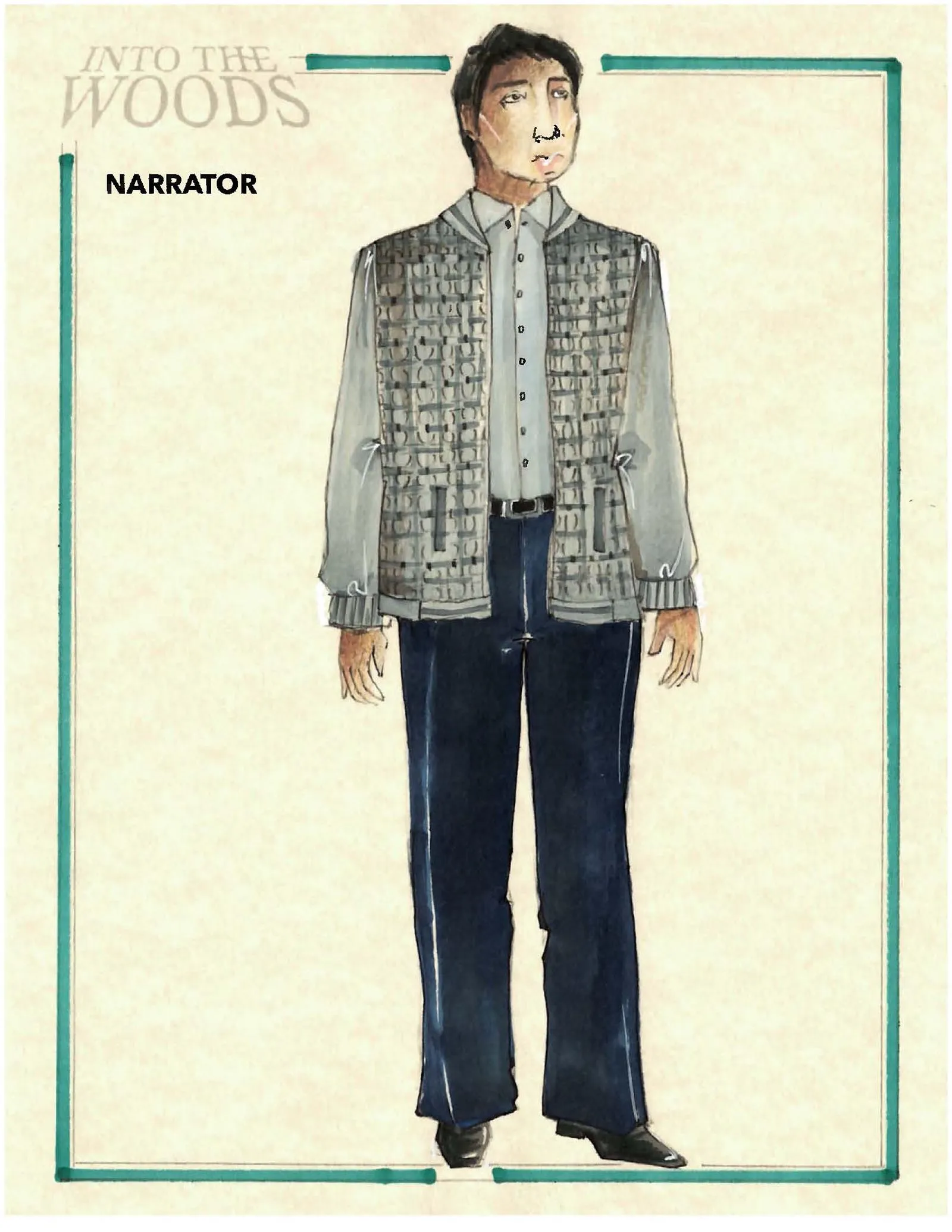

The Narrator, the Mysterious Man, and the Puppeteers

The Narrator was dressed in modernity, his jacket varsity in cut but woven in Inabel, bridging tradition and now. A salmon shirt kept him visible against the set. The same actor played the Mysterious Man, reimagined as the Ermitanyo, a spirit of caves, with a salakot hat tying him to the land. Even puppeteers were costumed with care: the Bird Puppeteer in navy blue, feathers appliquéd to his jacket, aligning him with Cinderella’s world of birds.