Photographed by Ralph Medoza for the September 2023 Issue of Vogue Philippines

Jeweler Natalya Lagdameo creates future heirlooms that trickle through the past, present, and future.

When we step into Natalya Lagdameo’s shop in the basement of The Manila Peninsula Hotel, we find her in a state of deep concentration, as if we’ve walked in on her working through some complex mathematical problem. Which on any other day, may just be the case, given that her nine-to-five involves designing furniture for the family business.

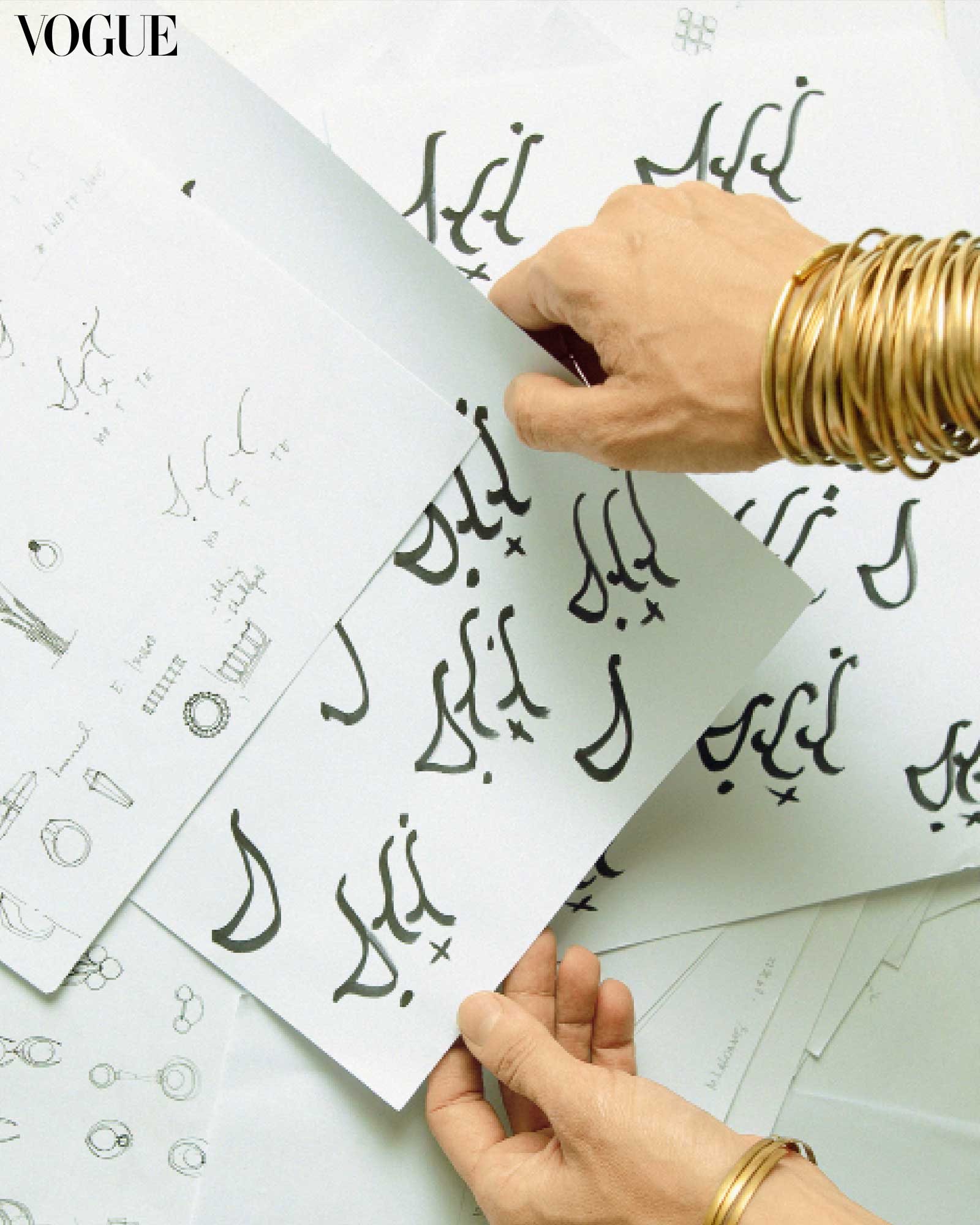

“Maybe you can help me,” she says, her fingers deftly sliding across threadbare strands of brass chain, orbs of antique glass, and polished onyx cylinders. Her signature stack of giniling bangles clinks gently against one another as she scatters her work across the jewelry display case at the center of her showroom. It is an elegant glass counter resting on a thick slab of Philippine hardwood that she designed together with her father.

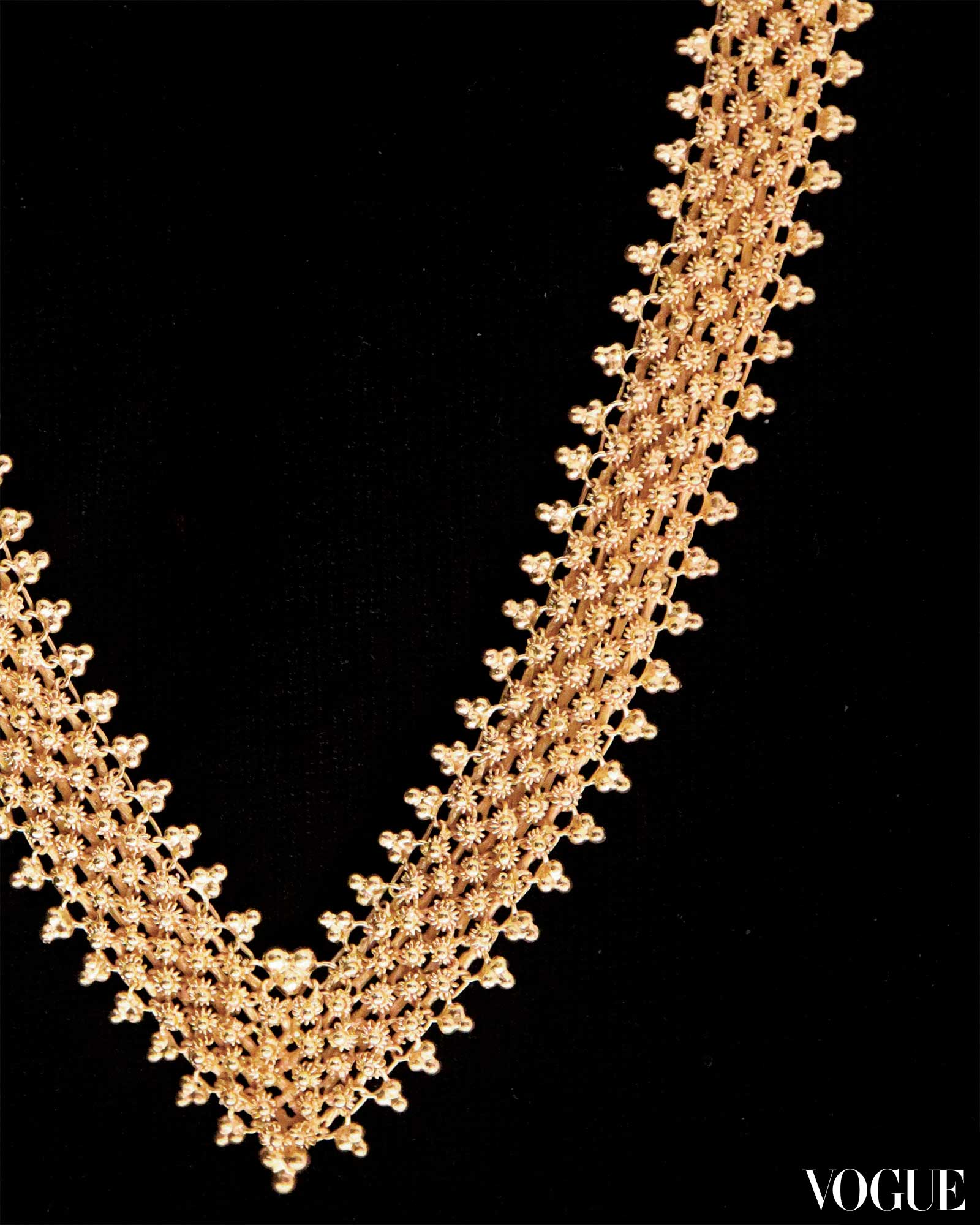

Lagdameo’s namesake line of jewelry has long garnered a dedicated following both locally and internationally, for its merging of old-world Filipino smithing techniques with contemporary flourishes. Among her showroom pieces include earrings made with Spanish-era tamburin beads (a design derived from traditional reliquaries such as rosaries) cascading like drops of water suspended between chalcedony, while another features golden antique-style kalabasa beads (named after their vegetal, pumpkin-like shape) hanging from a half-dome stud.

“What happens with my process is—you see this?” she gestures to the jewels laid out in front of her, “it’s a mess… but that’s how it works.” Lagdameo laments that rather than working on releasing a full collection at a given time, she is constantly in a state of production, sending both newly finished designs and restored antiques to her showroom almost weekly. “That’s what I enjoy doing actually,” she says, “just ripping things apart and putting them back together again.”

When it comes to antique pieces, the level of rehabilitation they receive depends on the condition that she acquires them in. “Sometimes it’s as if a piece has been run over, but there’s still an element that deserves to be saved,” she says. “If it’s beyond fixing, I’ll section it and find a different way to use it.” She pulls out a pair of earrings to illustrate one such reworked piece. A wave of glittering black beads hang from beneath a coin-like slice of mother of pearl. “These were individual antique beads. What we do is find a format that will give the older parts a new life. Actually, this is my whole palette: white, black and gold,” she shares. For many years, Natalya says she would only work with metals, but she started incorporating pearls, onyx, black diamonds. It’s a preference.

She credits her affinity with the past to a lifelong exposure to objects of antiquity. “I grew up in a house that was built in 1934, that my dad inherited from his grandparents.” Her father, renowned antique dealer and furniture designer Buddy Lagdameo, would fill their home with historical artifacts for both preservation and restoration. “My dad spent a lot of time in the Cordillera. When we were kids, he used to bring us up, so we learned a lot about their culture. He would do a lot of work with Cordilleran groups for carving and for artifacts.”

Along with his assemblage of furniture from bygone eras, her father would also amass a formidable collection of antique Philippine jewelry. One of her father’s heirlooms would later come to define Lagdameo’s roots as a designer: the giniling, a strip of coiled brass traditionally worn by both men and women from the Cordillera. “When my dad offered me five from his original collection, I grew more interested in traditional jewelry because I realized that they were actually made with the Filipina in mind,” she says. “They’re the correct size, the correct material… they suit us.”

In that society, she explains, you wore your wealth. “So the giniling was how you showed your rank,” Natalya says. “Richer families who maintained more terraces on the mountainside would have them in metals like gold. But ev- eryday giniling was made of brass. Its real use was for the protection of the wrists during the harvesting season. When they would cut rice or dig up root crops, it would protect their wrists from the blade.”

Whereas the traditional giniling features a single, lengthy brass wire coiled repeatedly around the forearm, Lagdameo’s interpretation takes the form of a set of 10 sleek, open brass bangles dipped in 22-karat gold that is sourced locally from small-scale suppliers. “This is who I am, from the elbow down.” She reflects on the stack of bangles on her arm that has become her calling card, jangling them ever so slightly. By now, she has kept one sample bangle on her arm from every batch of giniling that she has ever had produced. Her current stack? Forty. And much like it was traditionally intended to be worn, Lagdameo reveals that her giniling rarely leaves her wrist. “I would rather design things that people wear every day, rather than be the one in the box.”

The production time per giniling batch, it’s worth noting, takes over three years to fulfill. One of the reasons behind which is that Lagdameo chooses to follow the ebb and flow of the agricultural cycles up north. “Production for my jewelry is scattered, all over from the north to south, so I don’t actually maintain goldsmiths at my office,” she explains. “I work with groups in the Cordillera and prefer not to remove them from where they live so it’s not intrusive to their family life. They’re primarily farmers, so being plateros comes secondary. When it’s planting season we stop production, and when it rains or they’re waiting for their crops, we work. I prefer to follow their life cycle.”

There seems to be a parallel that runs through all the elements that make up Lagdameo’s distinctive creative process. From her singular ability to pluck disparate fragments from the past in order to create something new, to her bucolic, unhurried approach toward production and consumption. It all seems to trace its roots back to this lifelong connection to the mountains. To the need to honor the shared histories and heritage that connect us to one another.

- Tomorrow Land: Paying Homage to Bukidnon’s Greener Pastures

- Strands of Time: Filipino Culture Expressed in Avant-Garde Translations

- If Gems Could Talk: Alahas Tells the Story of Philippine Identity through Jewelry

- Vogue Talks: Creative Discoveries and Handcrafted Legacies with John-Paul Pietrus and Suzette Ayson