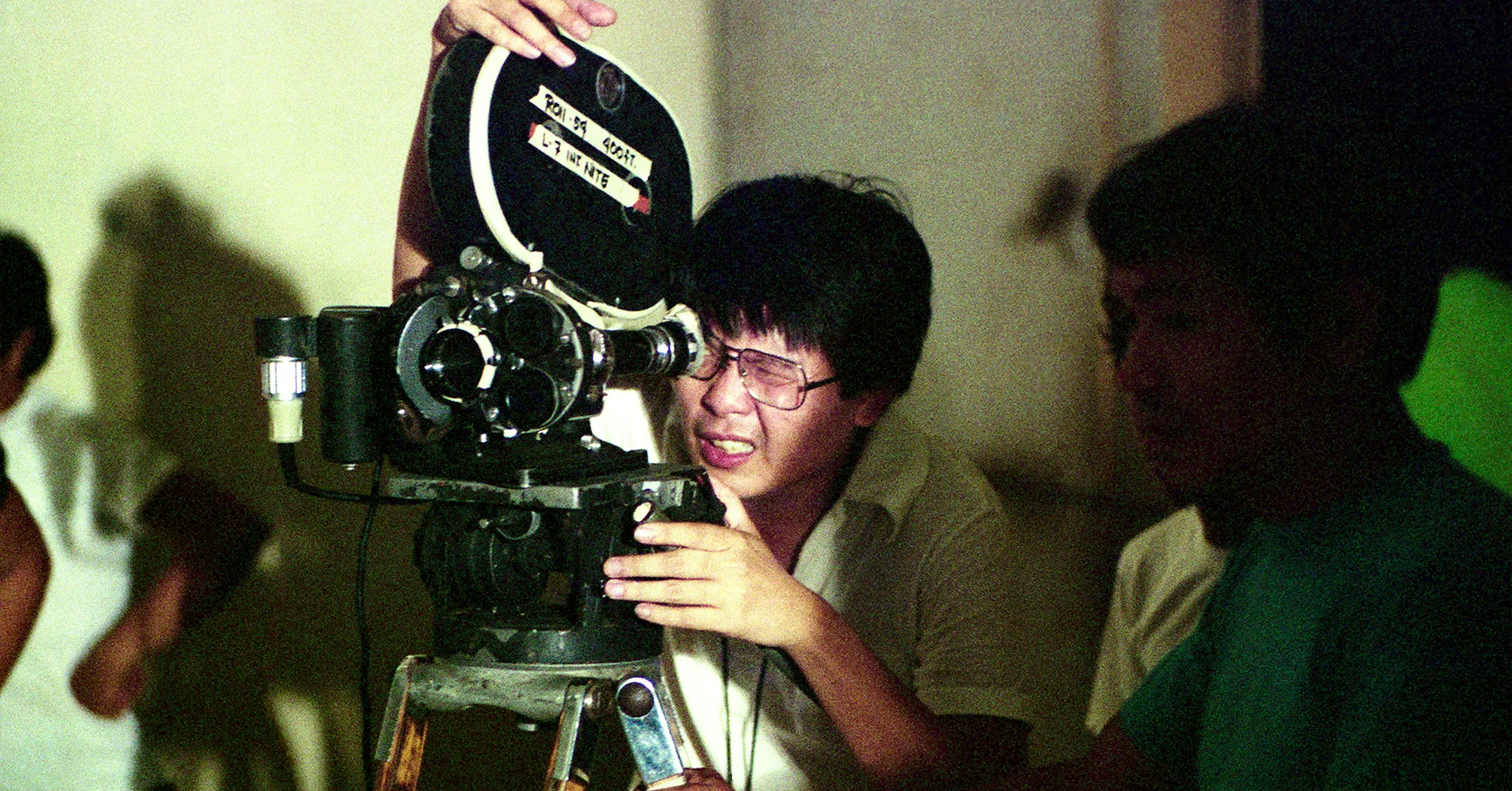

The Filipino filmmaker Mike De Leon (pictured here, on the set of his film Rites of May) is the subject of a month-long retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Courtesy of Mike De Leon

The Filipino filmmaker Mike De Leon (pictured here, on the set of his film Rites of May) is the subject of a month-long retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Courtesy of Mike De Leon

In 1982, The New York Times reported that there was “a search for excitement” at the Cannes Film Festival. After a year when the French presidential elections and an assassination attempt on the pope dominated the news cycle, not leaving much room for film chatter, the festival’s organizers wanted to make its 35th anniversary a lively affair. Showing new films were major names like Michelangelo Antonioni, Werner Herzog, and Jean-Luc Godard. And closing the festival? Steven Spielberg’s future sci-fi classic ET, premiering out of competition three months before it would open in the United States.

Somewhere in that shuffle, a 35-year-old Filipino filmmaker called Mike De Leon was causing excitement of his own. For his Cannes debut, De Leon screened two feature-length films at the festival’s Directors’ Fortnight—Kisapmata (In the Blink of an Eye) and AKΩ Batch ’81—becoming only the second filmmaker to do so. Both made enough of an impression that when the German director Wim Wenders asked some of his fellow filmmakers to participate in his documentary Room 666, in which he posed questions about the future of cinema, he included De Leon in a lineup with the likes of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Godard, Herzog, and Spielberg.

Forty years after his coup at Cannes, though, Mike De Leon is hardly a familiar name to most cinephiles outside the Philippines. While succeeding projects continued to screen at major festivals—his 1984 film Sister Stella L. competed for the Golden Lion in Venice—extended breaks from directing and the challenges of working in a developing country left him largely unknown to international audiences.

Until this year, at least. In May, a new restoration of his first film, Itim (Rites of May), premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. And this month the Museum of Modern Art in New York unveiled “Mike De Leon: Self-Portrait of a Filipino Filmmaker,” a retrospective that brings together all of De Leon’s work as a writer and director. Josh Siegel, a curator in MoMA’s department of film, first came across De Leon through the 1975 Lino Brocka classic Manila in the Claws of Light, for which De Leon served as cinematographer and producer. “I became intrigued by this guy who I learned had also been a writer-director on top of being a producer and a cinematographer,” Siegel says. “So I started watching some very crummy copies online of [his work]. I kept thinking, This guy is a major discovery, at least for U.S. audiences.

The Filipina filmmaker Isabel Sandoval, whose film Lingua Franca premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2020 to critical acclaim, remembers catching De Leon’s films on TV as a kid growing up in the Philippines. “Mike De Leon seemed to be the kind of Kubrick of our cinema,” she says. “His sensibility is quite eclectic, and he not only dabbled but really excelled in various genres.”

The power of De Leon’s work is most potent in one of the films he screened at Cannes in 1982. In the Blink of an Eye is a claustrophobic chamber piece of a thriller that, for Sandoval, is up there with Kim Ki-young’s 1960 classic The Housemaid. A horror film about filial piety, the layered In the Blink of an Eye goes beyond genre thrills to skewer both patriarchal family dynamics and, indirectly, the oppressive strongman leadership of the Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos, who at the time of the film’s release was on his ninth year of martial law.

“He is a deeply courageous filmmaker,” Siegel says. “He’s willing to provoke very, very powerful people in sometimes very incendiary ways.” In recent years, De Leon has released short films that have drawn parallels between the bloody Marcos regime and Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs. “[This] is his attempt to come to terms with the fact that history is cyclical and dictatorships and exploitation and corruption are rearing their ugly heads again, not only in the Philippines but across the world.”

Yet De Leon could do levity too. In 1980’s Will Your Heart Beat Faster?, for example, he creates a hilarious, rollicking romp of a film that manages to shape-shift from comedy to action to musical in the space of 104 minutes—all the while touching on issues of imperialism and blind faith. “The whole point is to call attention to forgotten or neglected chapters of film history,” Siegel says of MoMA’s film retrospectives. “We have a steady beat of the so-called masters, but then there are the forgotten masters or the masters in their own countries who are inadequately acknowledged abroad. These are filmmakers that aren’t necessarily household names, but they ought to be. Very much like Mike De Leon, [a lot of them are] very resourceful filmmakers who worked on shoestring budgets and knew how to edit to make incredibly taut, no-fat-on-the-bones movies.”

Shown alongside De Leon’s films in the retrospective are some of the surviving classics from the great Filipino film studio LVN Pictures, which De Leon’s grandmother Doña Sisang founded in 1938. They make an important addition to the retrospective’s portrait of De Leon, identifying cinema as not only the world he worked in but also his birthright.

Most Philippine films from the LVN era of the 1930s to the 1960s—and even De Leon’s decades of peak productivity in the ’70s and ’80s—have been lost to the ravages of time, making the MoMA screenings a rare privilege. De Leon, now 75, talked about this in his conversations with the film scholar A.E. Hunt in 2020. “Nobody knew about the vinegar syndrome at that time,” De Leon told Hunt in Filmmaker Magazine. “I myself thought that the black-and-white films would last forever.”

In recent years, De Leon has made it his priority to save as many of those films as he can. “They cost me a lot of money, but I rationalized it by thinking it was my father’s money anyway, the inheritance, I mean,” De Leon said in June. “I didn’t want his legacy, my grandmother’s, and mine to just dissipate in time. It is also because we Filipinos have very short memories and have very little interest in preserving our cultural heritage. If I could save more LVN films, I would, but most of the good ones are gone.”

Another thread that runs through some of the retrospective is De Leon’s collaboration with Charo Santos-Concio, whom he introduced to audiences as a new actor in Rites of May in 1976 and later collaborated with as a producer. Decades after their work together, Santos-Concio became chief executive officer of the largest media organization in the Philippines, ABS-CBN, and one of the most powerful women in media in Asia. “Everything I know about the art of filmmaking I learned from Mike,” Santos-Concio says. “As early as [my first film], he already taught me sound design, musical scoring, editing, everything that happens during post. Can you imagine? I’m so lucky.”

More recently, Santos-Concio appeared as the titular character in Lav Diaz’s Golden Lion winner The Woman Who Left. But her work with De Leon, in films where she tended to play seemingly vulnerable women with surprisingly deep reserves of strength, remains her signature roles. “I think she’s one of the great unsung actresses,” Siegel says.

“Their collaboration worked because I think they’re both intellectuals,” Sandoval says. “As an actress, Charo brings to a role a certain kind of intellectual quality. And her performances are not melodramatic—they’re always women who have a certain interiority to them. And she knows, as a production person as well, that her performance is one piece of the puzzle to Mike’s vision.”

Beyond the traditional director-muse dynamic, Santos-Concio says she felt empowered on De Leon’s sets. “We did not label each other as, ‘You’re the director, I’m the actress.’ We were two human beings collaborating. There was so much respect for his work, respect for his gift—and that’s also what he gave me.

“He would say, ‘I only work with intelligent people,’” Santos-Concio continues, breaking into a laugh. “‘You’re not a robot here.’ So our conversations were very engaged. Sometimes he would consult me on certain things, then I would give my input. During editing, he’d sometimes make two versions and I’d be there and he’d ask me, ‘What flows better, Charo? This sequence before this sequence? Or the other way around?’”

The MoMA retrospective comes at a time when Philippine cinema is once again making its presence felt on the world stage—be it through the Oscar buzz around Dolly De Leon’s (no relation) scene-stealing performance in Triangle of Sadness or well-received efforts by a new generation of buzzy young filmmakers like Sandoval. In the past, some critics deemed the kind of Philippine cinema that triumphed at international festivals poverty porn, catering, as Amy Qin put it in The New York Times in 2016, “to a widespread perception of the Philippines as a bleak, impoverished place of slums, corruption, and drugs.” Mike De Leon’s films have always avoided such characterizations.

“MoMA, as one of the most prestigious museums in the world, is essentially an arbiter of taste, of what is considered great art,” Sandoval says. “It’s kind of like that imprimatur from MoMA, saying that Mike De Leon belongs in the pantheon of the auteurs of world cinema. Especially since most of his output was in the ’70s and the ’80s, it goes to show that Philippine cinema—being part of what we know as third-world cinema—is not just all social realism.”

With it, the West is once again reminded that the cinema of developing countries like the Philippines has always been here, in conversation with the rest of the world, and more than worthy of consideration. “There are other voices that are just as fascinating and perhaps even more daring and brave,” Sandoval says.

“Mike De Leon: Self-Portrait of a Filipino Filmmaker” is on through November 30.

This article was originally published on Vogue.com