Conservation may be a tireless job, but Ann and Billie Dumaliang are going to do it forever.

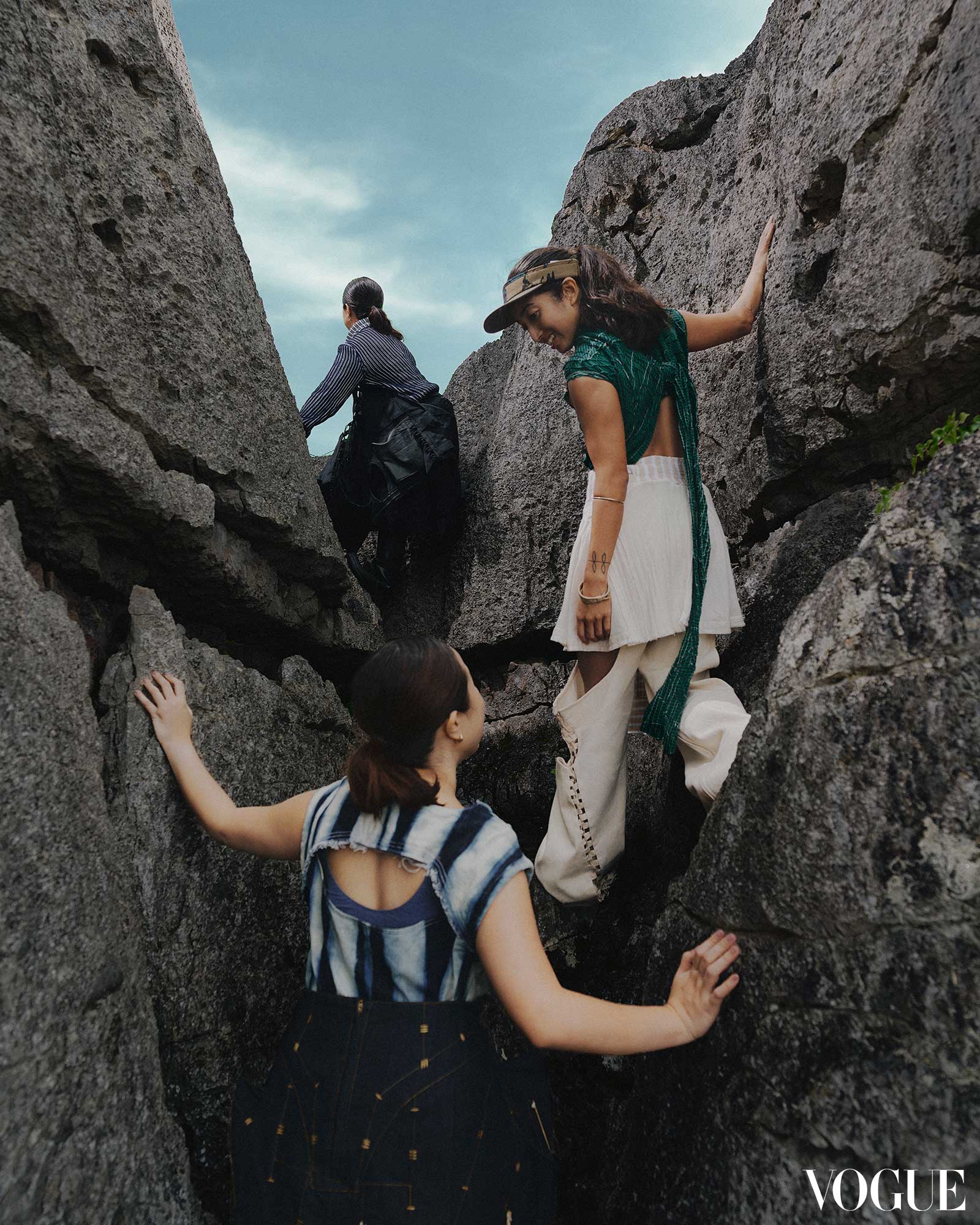

Just before sunrise, Ann and Billie Dumaliang led the way to the peak of a rock formation known as Tatay. It is the highest point in Masungi, from where you can survey a vast landscape of karst and forest, a green corridor of some 2,700 hectares that the sisters have devoted their lives to protecting and restoring. They’ve grown up with Masungi and have always thought of the place as a sibling. “Our dad probably spent more time here than with us. So yes, it’s like our younger brother,” says Billie. “And it’s also like my dad’s mistress. But the time that was spent caring and protecting the area was just infectious to everyone on the property, so that’s how we grew to love it.”

There’s a saying that we will only conserve what we love, and we will only love what we understand. How do we begin to understand a world that is so wide? It begins with getting to know a place and its inhabitants: the tide pools at the shore, the wilderness at the edge of the city, your backyard garden. Spending time in nature, being with nature, and entering into conversation with everything around you. Seeing for yourself the intricate web of relationships between the mushrooms and the trees, the birds and the seeds, finding ourselves belonging to this web of life, and approaching creation with the reverence and enchantment that we might have had when we were children.

“We’re so disconnected from nature, but if we bring back that value of empathy and the love for nature, you can get more done on the ground and make a difference,” says Camille Rivera, marine biologist and co-founder of Oceanus Conservation, a science-based organization focused on restoring mangroves around the Philippines. Taking the love and respect for nature to its logical next step, Camille dreams that the rights of nature will be recognized, citing countries like Panama which recently granted Nature the same legal rights as humans, prioritizing the needs of the ecosystems over the desires of society. “We always extract and exploit, so we need to make sure that there are rights for nature and for the animals that live within the ecosystem,” she says. “I really hope to see that in the Philippines as well, as we are one of the most biodiverse countries in the world.”

Indigenous communities have long held the sacredness of the natural world; they have always shared a spiritual relationship with the Earth. A recurring declaration among each of the women in this feature is the importance of holding space for Indigenous voices and knowledge, which they have come to know firsthand in their various advocacy work with communities on the frontlines. “If we see Indigenous solutions that have been working for thousands of years, those are the solutions that we should be channeling all our energy into. And that’s where we find hope,” says Tasha Tanjutco, who co-founded charity organization Kids for Kids and creative consultancy Tayo with her sister Bella when they were teenagers. On hope, Bella adds, “When you work with communities, that’s where we find the most energy and hope because the work is not just a one-transaction thing. It’s something that’s collaborative.”

Writer Nicola Sebastian similarly witnessed how communal responsibility works while researching for Homelands, photographer Jacob Maentz’ book documenting over 40 Indigenous communities across the archipelago: “I learned so much of what community and collaboration looks like. In a community with good leadership, there’s this sense of shared investment where everyone is involved, everyone decides together.” Nicola believes that, at a deep level, Filipinos do know how to collaborate and act for the collective good. The project of Emerging Islands, the arts organization she co-founded in La Union, seeks to foster greater co-creation and collaboration around ecological issues.

Issa Barte, an artist and co-founder of youth organization For The Future, holds art workshops in Indigenous and climate-affected communities with the goal of empowering kids to tell their own stories. With the Aetas of Yangil in Zambales, she showed 10 teenagers how to take photographs with a disposable film camera, and set them off with the question, “Why should your home—your forests, rivers, trees, and birds—be protected?” Their photographs changed the way she thought about the climate crisis. “It is a lesson I am learning from the children—about how our relationships to our ecology could shift our sense of self, of beauty, of climate—and ultimately help us envision a better future for all,” Issa writes in an essay. “They are teaching me an inward route about how our solutions exist within our own communities, our own ecologies, our own truths.”

As daylight started to fade over the Upper Marikina Watershed, the women went deep into conversation about conservation. They don’t really have an agreed upon name for what they do—they insist that the true environment defenders are the rangers and those on the frontlines—all have been transformed by the forces of nature. All have been in deep communion with its beauty, seen up close its devastating power, and understand that the path forward involves love, empathy, and compassion, for humans and non-humans alike.

“Our relationships to our ecology could shift our sense of self, of beauty, of climate“

Reflecting on a year that began with the cancellation of quarrying at Masungi and ended with “No More Cruel Summers,” a Taylor Swift-inspired advocacy action at COP28, Ann says that “it’s really beautiful to see that solidarity exists on the local ground and on the international stage.” Still, the memory that always keeps hope alive for the Dumaliangs despite the challenges is the day the Indigenous groups and the military got together at a bulalohan in Rizal and shared a meal. Previously on opposing sides of the often dangerous conflict, they’ve both become Masungi’s strongest partners on the ground. “You sit there and have bulalo with them and see them find ways to help each other on common ground—on taking care of home, on national pride,” she says, getting teary eyed, “on loving this country.”

THERE IS SOMETHING IN THE WAY ANN AND BILLIE DUMALIANG SPEAK ABOUT CONSERVATION THAT REVEALS TO YOU THAT THEY’VE BEEN TALKING ABOUT IT FOREVER. In another life, Ann says she’d be an engineer; Billie, an entrepreneur. Or a K-Popstar. “They look like they’re having so much fun!” she laughs.

But in this lifetime, in their words, Masungi is a “forever thing.”

Conservation is in their DNA, passed down from their father. Their answers are instinctive, informed by years of lobbying against political rivals and bonding with scientists. Their shared vocabulary is equally diplomatic and academic. They geek out about snails even when they are the only two in the room that can understand.

Despite their young age, their work is prolific.

Aren’t they tired?

“Tired? Um… yes,” Billie says, laughing, before adding “physically, mentally, spiritually” for emphasis. “But we can’t stop. Eight years have passed in the blink of an eye.”

Ann and Billie are trustees of Masungi Georeserve, a multi-award-winning conservation site and geotourism destination tucked away in the rainforests of Baras, Rizal. It was in 2017 that these restoration efforts were formalized. Over 68,000 native trees have been planted to this day. People will recognize the name Masungi Georeserve because they’ve stepped foot on its wildlife trails, which take them to an abundance of trees, jagged cliffs, and unique karst formations, an hour-and-a-half drive from Metro Manila.

“It’s always been about getting more people to love Masungi,” Ann says. “That’s what the trails are for.” It is a veritable forest of dreams, and as they nurture it, people will come.

As karst landscapes make up only 10 percent of the entire world’s topography, the biodiversity of Masungi Georeserve is increasingly valuable. It gives birth to endemic wildlife, both plant and animal species that can only thrive under these rare and specific circumstances.

But just a few decades ago, this land was barren. Privately managed by the Dumaliang family in partnership with the Philippine government, Masungi Georeserve is one of the largest and most successful reforestation efforts in the Philippines. The funds generated from its popularity in geotourism are used to conserve the area and raise awareness. But the site is not without challenges.

“This year has involved a lot of relationship building. I used to kind of believe that, you know, all of this politicking could be solved in a few years, but it looks like it’s something that will be there… forever,” Ann says.

It takes at least 20 years to grow a forest, and a lifetime to protect it.

When asked where they find the energy to keep going, the sisters don’t give places but a list of names: Tatay Rudy, Tatay Karling, Rolly Pena, Gina Lopez.

These are names of two elders from the Indigenous Dumagat community, a revolutionary geologist, and the former DENR Secretary. All champions of Masungi Georeserve who have passed away.

“Oh no, I always cry, okay!” Ann warns, not long before the tears start falling. She begins by saying that when she first consulted Tatay Rudy and Tatay Carling, Masungi as we knew it hadn’t even begun.

“They’ve always asked us to help safeguard their knowledge about the place and the plants and to share it with others and make sure it isn’t forgotten. They were already in their 70s,” Ann says. “That’s why I get so emotional. It’s not just them, it’s Gina and it’s Sir Rolly… all these champions who spent the last year of their lives, their whole lifetimes, and then passing the buck on to us. They had so much heart. And they aren’t here anymore. ’Di nila nakita. [They didn’t get to see it.] I guess that’s why I cry. I don’t want it to die with them. I want it to continue. I don’t know how else to express it.”

A long silence follows. There is still much more work to do.

The determining factor in whether or not they will succeed is how much support they receive from the government. This is likely the reason why we talk about former DENR Secretary Gina Lopez, a champion and a supporter.

“Gina listened. She went on the ground. She had a true heart for environment defenders and grassroots practitioners,” Ann says. “She’s genuinely for empowering communities and empowering conservation. When you say you have a multistakeholder, it’s a genuine and authentic multi stakeholder approach and she knows how to bring everyone together and build on their knowledge and capabilities. She’s courageous. She acts on things with urgency. Maraming kailangan mangyari [A lot of things need to be done] but she will take the necessary first steps. People always say ‘slow down, it’s not a marathon’ but Gina understood that a marathon is composed of sprints.”

The majority of the time spent talking to the Dumaliang sisters, Anna and Billie spend talking about other people: their mentors and their team members. Their deep ecological empathy tunes into the actions of those connected to the community.

“They’ve always asked us to help safeguard their knowledge about the place and the plants and to share it with others and make sure it isn’t forgotten“

The last person they mention is Ate Irene, a middle-aged mother, one out of roughly a hundred park rangers who look after the Masungi Georeserve. She walks 30 minutes every day to get to her station in Masungi, despite her bad knees. She sits quietly in the back during meetings with Rangers.

For almost three months, Ann missed her. “There was just so much work to do in Metro Manila…. My time was divided between meeting people in coffee shops and being in Masun- gi. So I didn’t see her for a long time. But one day, she comes up to me and says she didn’t understand before but now she sees what can happen. That now, she loves every seedling she plants. That day she ended with, ‘You haven’t given up, right?’

I said ‘No, I haven’t given up, but it’s nice to know you haven’t given up either.’”

Introduction by Audrey Carpio and Nina Unlay. Photographs by Artu Nepomuceno. Fashion Director: Pam Quiñones. Beauty Editor: Joyce Oreña. Stylists: Renee de Guzman, Roko Arceo. Makeup: Angeline Dela Cruz. Hair: JA Feliciano, Mong Amado. Talents: Ann Dumaliang, Bella Tanjutco, Billie Dumaliang, Camille Rivera, Issa Barte, Nicola Sebastian, Tasha Tanjutco. Art Director: Jann Pascua. Producers: Anz Hizon, Bianca Zaragoza. Multimedia Artist: Gabbi Constantino. Production Assistant: Bianca Custodio, Patricia Co, Patricia Villoria, Tinkerbell Poblete. Photographer’s Assistants: Aaron Carlos, Choi Narciso, Mark Tijano, Odan Juan, Sela Gonzales, Rojan Maguyon. Stylist’s Assistants: Giselle Barnachea, Neil De Guzman, Ticia Almazan. Makeup Assistant: Jian Santos. Hair Assistants: Kyle Denzel Celis, Marjorie Caballos. Shot on location at Masungi Georeserve.

- Riding Waves, Growing Stories: Nicola Sebastian’s Path To Climate Justice In The Philippines

- Creativity As Catalyst: TAYO Philippines Founders Tasha and Bella Tanjutco On Using Creative Solutions For Climate Work

- Issa Barte On Amplifying Indigenous Voices And The Role Of Culture In Climate Action

- Camille Rivera On Bringing Life Back To Communities Through Mangrove Conservation